I was stabbed 14 times in the hospital where I work as a brain surgeon - it made me a better doctor

The quick work of Australian neurosurgeon Michael Wong's colleagues saved his life.

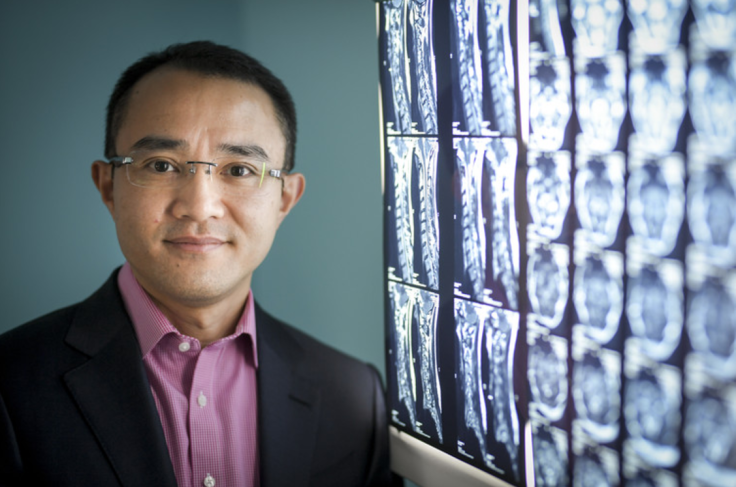

Michael Wong, University of Melbourne

The attacker struck in the foyer of Melbourne's Western Hospital on an otherwise ordinary Tuesday morning.

I'd just arrived, and had my mobile phone out to ring my registrar to ask whether I had time to nick up to the wards and see my patients, or whether I needed to go straight to the outpatient clinic.

At first I thought I'd been pushed in the back. Then I slipped on my own blood and fell to the floor. I was being stabbed, over and over again. I remember turning my head so a blow coming at my eye instead landed on my skull. Being a neurosurgeon, I could all too easily picture the blade piercing my brain through the eye socket.

I remember people yelling, and the tug on my clothing as I was dragged along the floor through a set of double doors to safety and along the corridors to Emergency, leaving a trail of blood.

The full story of my rescue and the incredible bravery and people behind it – including nurses, an intern, a hospital technician and a leukaemia patient – only emerged much later.

I remember looking at my arms and hands; there were deep cuts. I remember being aware that I was breathless, and trying to slow my breathing – not knowing I had a punctured lung. I remember the look of absolute horror on my registrar's face, as I was wheeled past him on a hospital trolley on my way to surgery.

I remember asking someone to call my wife.

I remember the pain of being prepped for surgery, the sting of antiseptics on open wounds, and asking the anaesthetist why they couldn't put me to sleep first. (They didn't tell me it was for fear that I would go into arrest, and they wanted to wait until the full medical team was assembled.)

Hazily, I remember waking with a tube in my throat and seeing my wife – then things fade out until I woke to the moment of truth.

I was lucky

It was 2am and I was alone, in a hospital bed. I knew where I was and what had happened. The big question, my big fear, was that I might have had a stroke as a result of the attack. I moved one side of my body, and then other. Both sides worked. It was then that I felt I would be okay in the end.

All up, I was stabbed 14 times. But I was lucky.

I was fortunate that instead of being bystanders, brave people intervened to get me away from my attacker. The surgical team did an incredible job of stitching me back together, with a cardio-thoracic surgeon removing part of my lung to stem bleeding and three plastic surgeons mending severed tendons and muscles in my arms and hands.

I was also lucky to have a supportive family who helped me through the process of recovery.

My arms and hands were in splints for six weeks. I couldn't eat without help, or get dressed. I couldn't wipe my own backside – at times, I had my eight-year-old son helping me in the bathroom. If that's not humbling, I don't know what is.

Ironically, there was part of me that was pleased to have some time off from the constant pressure to work more and more hours in the resource-constrained public hospital system. At the time of my recovery, MH370 went missing, and I watched hours and hours of coverage on TV.

When the splints came off, I was fortunate to have a hand therapist who worked with me over the next 12 months to enable me to regain strength and movement.

I was also lucky to be able recover fully and return to work.

And I've been lucky that I don't seem to have been left psychologically scarred – other than disliking crowded areas in hospitals, and people walking behind me.

People ask how I can have escaped psychological damage. I think it's partly because in my career I've seen a lot of bad things – four-year-olds with malignant brain tumours, young people smashed to pieces.

I know bad things happen to good people so I didn't waste time asking why, instead focusing on what I needed to do to recover.

If anything, my experience has made me a better doctor – not from a technical perspective, but in terms of a deeper understanding of how it feels to be a patient, including the inconvenience and loss of control, the fear and pain. I came to understand that the essence of good care was time.

For the most part, I've compartmentalised the attack and put it away, and that seems to work for me.

Protecting staff

I don't enjoy revisiting the attack, but as someone fortunate enough to have survived I speak out on my experiences to campaign for better hospital security – most recently in the wake of a fatal one punch assault on Melbourne cardiothoracic surgeon Dr Patrick Pritzwald-Stegmann.

My attacker was mentally unwell. People ask me if "the way forward" is better mental health care. While that would be welcome, the solutions I'm calling for are simpler.

First, busy public areas of hospitals should have trained security guards in them. You can't have security guards everywhere, but I think it's realistic to expect they can be stationed in hospital foyers and outpatient clinics – as well as emergency departments.

Second, fewer areas of hospital should be public. All wards should be accessible only via swipe card access in the same way surgical theatres are protected today.

Third, hospitals should have secure entries for staff.

Hospital staff also need to play their part by taking the time to report violent incidents – ideally on easy-to-use streamlined report forms.

Management need to take the issue seriously – there's a good business case for investments that reduce occupational violence. Dealing with violent patients or bystanders wastes staff time. If staff are injured, they may need to take time off work for treatment. Indirectly, occupational violence contributes to stress that can lead to burn-out, psychological damage and employee turnover. There are also issues of legal liability.

A Fairfax analysis of Victorian hospital annual reports in 2015-2016, found there were 8,627 violent incidents reported – almost one an hour – with 1,166 resulting injuries. While it is commendable annual reports must include this data, and other states should follow suit, the true number is probably far higher due to under-reporting.

In the past year, in my own practice, I've operated on two hospital employees suffering severe back pain as a result of occupational violence at the hands of patients. It's not just physical pain they suffered, but emotional trauma. I had a grown man weeping in my rooms.

In the wake of the attack on Dr Pritzwald-Stegmann, but before his death, the Victorian Government hit the headlines with a new advertising campaign and a doubling of funding (to A$40 million) to the Health Service Violence Prevention Fund. Hospital administrators will be able to apply for funding for projects they believe will have the most impact.

While any funding is good funding, and gift horses shouldn't be looked in the mouth, this system relies on hospital administrators to be proactive and accurately judge the merit of competing proposals. Unfortunately, there are no guarantees the money will be spent to achieve the greatest possible impact across all public hospitals.

I did not know him personally, but clearly Patrick was doing valuable, life-saving work for the Australian community when he was cut down in his prime. And of course, he wasn't just a surgeon, but a husband and father too. It's a senseless loss that no family should have to endure, and one that tragically further underlines the importance of getting hospital security right.

Michael Wong, Neurosurgeon and Spinal Surgeon, University of Melbourne

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.