India is ignoring its growing acid attack crisis – but brave survivors are fighting back

Hundreds of women are attacked for rejecting marriage proposals or sexual advances, but acid is widely available.

"When I was attacked, my life was ruined. I wanted to study; I wanted to become a Bollywood dancer. But now look at me."

Three years ago 22-year-old Sapna had acid thrown at her by an angry relative after she rejected his marriage proposal. Since then, she has grown used to telling her story to journalists, but despite an almost-robotic recall of her horrific assault, there are moments when her emotional and physical pain seeps through.

It is in these moments that it is possible to catch a glimpse of a world where a small bottle of liquid can change somebody's life forever.

"Sometimes I have to be in hospital, sometimes I have to be in court, other times I have to be at the police station," Sapna told IBTimes UK in New Delhi, the exhaustion in her voice palpable.

"My attacker has been in jail but he hasn't been sentenced. The courts call me, ask me a few questions and send me away. It's been three years," she said.

In 2013, India's Supreme Court ordered federal and state governments to regulate the over-the-counter sale of acid in an attempt to reduce attacks on women and girls such as Sapna. Despite this, the chemical remains easily available and local organisations estimate that there are between 100 and 500 acid attacks in India every year.

IBTimes UK travelled to India to speak to some of the women who have been affected and find out why acid violence has become so common on the subcontinent.

A lifetime of pain

When Sapna rejected her relative's proposal, he began to harass her.

"My uncle's wife's brother liked me, but I didn't like him. He wanted to get married. His ego was hurt by this and he began to torture me and threaten me. Even then, I continued to reject him. He thought I was arrogant, and so he attacked me with acid," she said.

In a single moment in 2013, Sapna's life was shattered.

Her attacker was on a motorbike when he approached her from behind and threw acid on her. Although she spoke confidently, Sapna admitted that any recollection of the attack upsets her. She described the trauma she faced in the months following the attack.

"One day I was walking when a boy on a motorbike – like my attacker – drove past near me. It all came back to me. I was terrified and I thought it was going to happen again," she said.

Her problems stretch beyond the emotional scars she has been forced to live with. She went on to explain the difficulty she faces in everyday tasks, like taking a shower.

"For months after the attack, every time I showered with warm water it would remind me of the moment I was attacked. I had to shower with ice cold water in the middle of January just so that I wouldn't be taken back to that moment," she said.

Sapna has faced lesser day-to-day burdens that are side effects of her mental trauma.

"I'm never in the mood to leave the house. I have to cover up and go outside because my burns make me sensitive to everything. I'm sensitive to sunlight, to heat, to crowds. I can't wear nice dresses because my arms are scarred, my face is scarred. What's the point of wearing anything nice?"

A national problem

India is fast becoming synonymous with acid attacks. News coverage of such incidents has become almost a daily occurrence, yet little is being done to prevent the crime from occurring.

It wasn't until 2013 that the government introduced Section 326A and 326B into the country's Penal Code. This made acid attacks a non-bailable offence and imposed a minimum sentence of ten years in prison.

But there is an urgent need for prevention, rather than merely justice after the fact. Indian law states that acid can only be sold in licensed shops. But a lack of monitoring and regulation means that it is still easily available – and it's cheap.

"Despite the laws that have been put into place, acid attacks continue to happen as there's no regulation," said Shaheen, vice president of acid attack charity Make Love Not Scars. "Committing an acid attack is one of the easiest crimes."

Shaheen is a survivor of an acid attack herself, but she now chooses to focus her efforts on helping other women who have been attacked, rather than seeing herself as a victim. Her in-depth knowledge about acid attacks, the sale of acid and the law governing these acts in India was relayed with confidence as her own experience was set aside.

With Shaheen's help, Make Love Not Scars filed a Right To Information (RTI) request in an attempt to find out which parts of India had the highest number of acid sales. However, the government was unable to provide the group with this information because no one was monitoring the sale of acid.

"The government is doing nothing about this," Shaheen said. "A survivor becomes disabled for life after an acid attack. And where is the government in this? They're not there."

The subcontinent's 'obsession with beauty'

Ria Sharma, the founder of Make Love Not Scars, has spoken out about the "obsession" that India has with beauty and fairness. Having worked closely with survivors such as Sapna and Shaheen, she is certain that men use acid attacks as a way to ruin a woman's chances for a normal life in a superficial society.

"In India, a woman's standing is based on her appearance and the medieval thinking that a woman can't go out without a man," said Sharma. "If there's one thing you can control, it's the way you look. So when someone throws acid on a woman, he probably thinks that he is taking away a woman's standing in society."

The most common age group of women who are attacked with acid are those between 14 and 35. As with Sapna, most women are attacked after rejecting marriage proposals or sexual advances. Embarrassed by having been turned down, a man understands that by disfiguring the woman's appearance, no one else is likely to marry her.

But aside from marriage, acid attack survivors often cease to lead a normal life. Many find themselves unable to get jobs, while others drop out of school. As a result, women and girls end up shutting themselves off from the world, further aggravating the mental trauma that comes with the attack.

"India has this problem where we blame the victim a lot," said Sharma. "There's this instant alienation for acid attack survivors, where they're looked down upon. People ask if this happened to her, what did she do to deserve it? And the answer is that you can never do anything bad enough to deserve something like this."

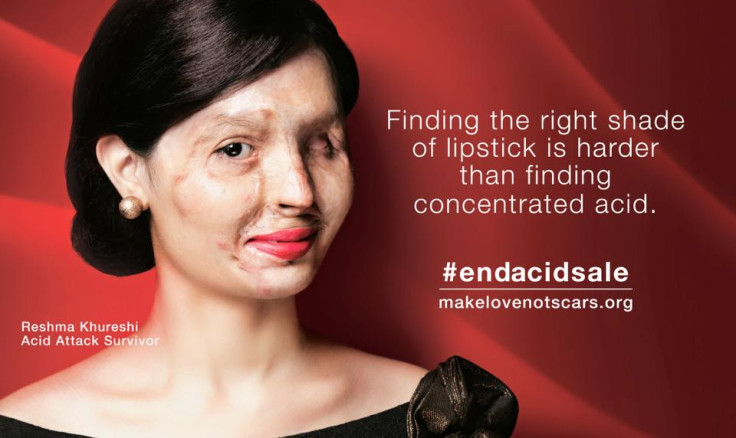

Reshma: A role model for acid attack survivors

In September 2016, Reshma Quereshi, a young woman who survived an acid attack in India, was invited to walk the ramp at New York Fashion Week.

"For a few moments, I couldn't even believe I would come in such a big place and walk on such a big stage," Quereshi said at the time. "I believe beauty is not external, but rather what comes from within."

Exactly one year earlier, the 18-year-old went viral when she created make-up tutorials as part of a powerful campaign for ending the sale of acid. It was one of the first times Indian society had been forced to open its eyes to the brutal reality of acid attacks, coming face-to-face with what acid did to Quereshi's face.

One woman's story travelled around the globe and shone a light on acid violence in India. The Supreme Court has ordered all hospitals in India to provide first aid treatment free of cost to the survivors, and acid attack cases that were pending in court have begun to see some movement.

Although it might take time until India is completely rid of acid attacks, stories such as Reshma's have proven that women can recover from the attacks – and can go on to achieve great things.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.