James Joyce's Ulysses: How to get the most from one of the finest novels around

The celebrations in Dublin and other cities around the world to mark Bloomsday on 16 June (Ulysses is set on that date in 1904) are likely to prompt many new attempts to read Joyce's most famous work. However, while hailed by many as the greatest novel ever, Ulysses is also one of the most daunting and setting it aside after the first 50 pages or so is a common experience.

That is unfortunate, because once you have mastered the novel, it is one of the most enjoyable literary experiences around.

Alongside its innovative brilliance it is always entertaining, frequently moving – and often hilarious. Joyce's comical animus for the conservatism of his native land is prominent from the off. There is a mocking parody of the Catholic mass in the opening chapter to set the tone, while chapter two features the provocative – for the time – scene of Leopold Bloom reading on the toilet. And so it continues, with an abundance of ribald fun woven into Joyce's scintillating streams of consciousness.

But preparation and planning are needed to access the entertainment. First, choose your edition with care. You need one with a thick wad of notes : Ulysses needs lots of explanation. My recommendation is Ulysses, edited by Jeri Johnson (Oxford World's Classics). Johnson provides an invaluable introduction and a myriad of footnotes.

Next, you require a crib. You will appreciate Joyce's stylistic pyrotechnics that much better if you know exactly what happens in each chapter. The New Bloomsday Book by Harry Blamires (Routledge) details all the novel's events in plain language.

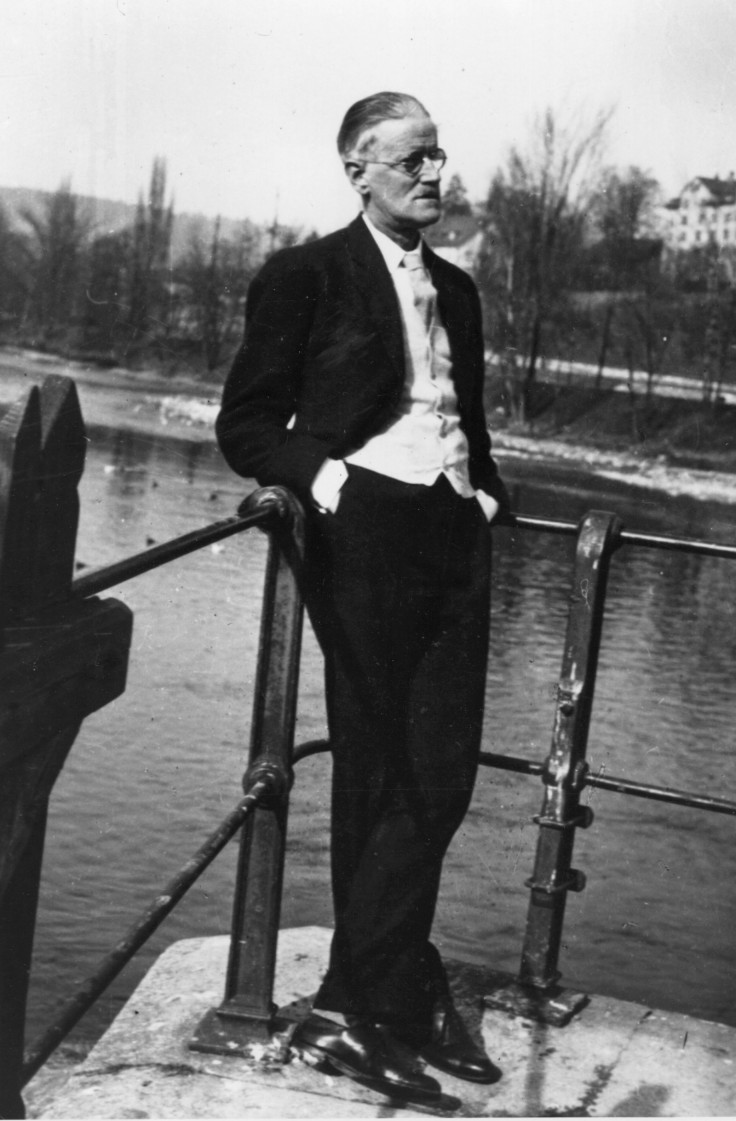

Ulysses is, in part, a parody of the main episodes in Homer's The Odyssey (Oxford World's Classics), so you may wish to read that too, though it is not essential. The Homeric parallels do not make a massive impact on first-time readers and, in any case, many of them will be familiar. Another worthwhile preliminary volume is Richard Ellmann's biography, James Joyce (Oxford Lives). It is engrossing in its own right and contains much useful contextual material on Ulysses. And it is a given that you've also read Joyce's Dubliners (Penguin Popular Classics) and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (Penguin Modern Classics).

Now be warned: reading Ulysses itself will take the equivalent of around two working weeks (factoring in seven hour days, five days a week). That is 10 times as long as most novels. So think about spreading your efforts over a longer period to make the project – and this most definitely is a project – manageable.

Do not begin at the beginning.

It makes much more sense to tackle the easier chapters first. Reading out of sequence will not affect your understanding of the book as a whole if you've done your preliminary reading and perused Johnson's introduction. Of the 18 chapters – and perhaps Joyce was having a sly laugh at our expense here – the most straightforward is the final one: Penelope. It is divided into just eight sentences and is otherwise unpunctuated, but don't be deterred. So kick off with Molly Bloom's soliloquy as she relaxes after her bout of adultery with Blazes Boylan and revel in one of the finest passages of prose in the English language.

A good approach to each chapter is to read its footnotes first, then the text and then the crib to make sure you know what's happening (and then, perhaps, the text again). The remainder of the easier chapters are (the footnotes and crib will give their titles; Joyce removed them from his final text, not wishing Homer to over-intrude): Telemachus (chapter 1), Nestor (2), Calypso (4), Lotus Eaters (5), Hades (6), Eumaeus (16) and Ithaca (17). Then have a go at the remainder, but leave the hardest of all until last. They are: Proteus (3), Sirens (11), Cyclops (12), Oxen of the Sun (14) and Circe (15).

Proteus is the reason so many first-time readers abandon the book around page 50 – it is a morass of literary and philosophical allusion to swamp the unwary, though bear in mind there is humour here too, because Joyce is mocking Stephen Dedalus's intellectual pretensions.

When you have read the novel in this easier-to-harder fashion, read it again from start to finish. This time it will be a swifter and simpler process. Promise.

There is so much to enjoy. As well as highbrow prowess, there is plenty of scabrous comedy, much of it contained in Bloom's absurd fantasies and trains of thought. The BDSM episode in Circe goes much further than anything in Fifty Shades Of Grey, as well as being incomparably more imaginative. Nausicca (13) is written in the style of romantic pulp fiction, despite its action consisting of Bloom masturbating over the sight of two young women on a beach – it is not hard to understand why Ulysses was banned in the UK for nearly a decade and a half.

After you've finished reading, if you wish to explore Ulysses further, there is a huge number of critical texts to keep you going. And you will want to consider tackling Finnegans Wake, a more sizeable project still, because by now you will be a Joycean and there'll be no turning back..

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.