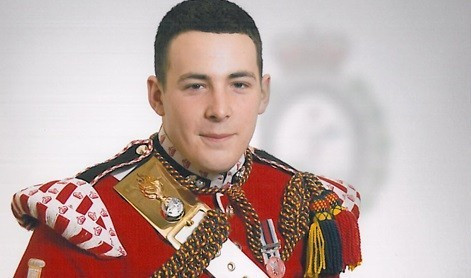

Lee Rigby Murder: How MI5 Monitors Terrorists Like Michael Adebolajo and Michael Adebowale

MI5 has come in for criticism from parliament over certain failings in monitoring Fusilier Lee Rigby's murderers.

Though errors were identified, MPs on the Intelligence and Security Committee concluded in a report that MI5 could not have prevented Rigby's murder.

The two men who killed Rigby – Michael Adebolajo and Michael Adebowale – were both known to intelligence services because of their activities. They were jailed for life over the gruesome killing on the streets of daytime Woolwich, in which Rigby was almost decapitated.

Adebolajo, 29, had been investigated by MI5 five times between 2008 and 2012 over suspected terror-related activities. Adebowale, 23, was investigated twice by MI5. Once in 2011 and again in 2012 because of his interest in extremist media.

So how exactly does MI5 operate when it investigates individuals and why did these two men slip through the net?

First of all, suspect individuals have to be identified.

These can come from tip-offs elsewhere in the security and defence system, such as GCHQ, foreign intelligence services, or from past MI5 investigations, as well as tip offs from sources known as "agents".

GCHQ, which is the communications arm of the UK intelligence services, told MI5 in 2011 that Adebowale had been accessing extremist material on the internet, prompting the agency to start digging.

Adebolajo was first identified as a suspect in 2008 when he was linked to a "subject of interest" already under investigation by MI5 for having "acquired items that could be used for terrorist purposes, and who had previously met members of Al Qaeda Core", according to the Committee report.

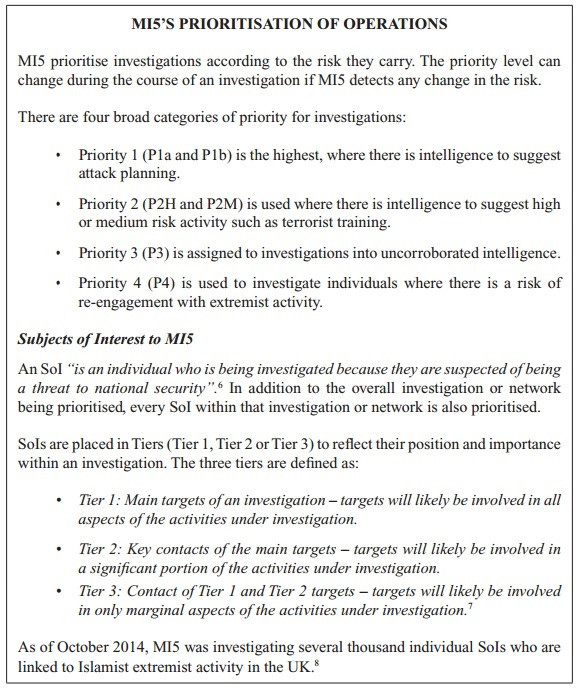

Then the case is given a priority level.

MI5 assigns all its cases a level of priority because there are so many investigations to handle and a finite amount of resources. The priority is determined primarily by the risk the suspect poses and there are four categories. There are a further three tiers for subjects of interest.

After having been identified as a subject of interest, MI5 collated all available intelligence on Adebolajo. The report recommended that extra intelligence be gathered: his recent call data, a current address and his digital footprint.

But other subjects of interest deemed to be of higher risk were increasing their activity. A decision was made to priorities resources on them because of the urgency of the threat. Adebolajo was not seen as a part of this threat, so his case was temporarily shelved.

In Adebowale's case, it took eight months from the first notification of MI5 that they should look into him to the start of the investigation, for which the agency was criticised by MPs. But the case was low priority and looking at extremist material was not a strong enough justification for deeper surveillance, for which MI5 must get approval from the government.

If MI5 wants to conduct "intrusive surveillance" it must get approval from a Secretary of State.

If MI5 thinks there needs to be more intelligence gathered from a suspect, which requires "intrusive surveillance" such as tapped phones and bugged vehicles, it must seek a warrant to do so from the relevant Secretary of State, like the Home Secretary.

This is written into the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000 (RIPA), which governs much of MI5's activities by laying down what it can do day to day, such as authorising the use of "covert human intelligence sources" – or agents.

For a warrant to be given, MI5 must provide enough evidence to show that it needs one "in support of the prevention or detection of serious crime", says RIPA. The two principles are that the surveillance must be "necessary" and "proportionate".

Then MI5 officers begin monitoring the suspect to gather intelligence. This surveillance comes in all sorts of forms. It can be in the form of an MI5 surveillance officer following a suspect, taking pictures of their activities, who they meet, where they go. It can be the bugging of homes and vehicles. It can be the interception of communications, like phone calls, emails, texts, private internet messages on social media.

And information comes from agents, who have been recruited from around the suspect. They may know them from a community group, or be related, or a friend, or colleague. Once MI5 identifies someone who they can recruit as an agent – a tricky process in itself – they use them to gather as much inside information as possible on the suspect.

In the case of Adebolajo, MI5 eventually thought there was enough evidence to justify intrusive surveillance. This followed his arrest in Kenya alongside five other young men who were planning to go to Somalia and join the terror group al-Shabab. He was deported back to the UK and questioned by police.

MI5 collected communications data from Adebolajo, used surveillance to find out where he lived and had agents near him. Other techniques were not disclosed in the MPs' report, but MI5 said none of the intelligence gathered was showed he was planning an attack. They also said he was difficult to investigate "due to his security-consciousness". Eventually, in 2012, they ended all intrusive surveillance of him and said they'd keep on top of his activities by monitoring closely subjects of interests with who he had contact.

As an MI5 official told MPs, "we threw the kitchen sink at it". But to no avail.

"MI5 rarely have complete coverage of their targets, even those who are under intensive investigation," said the report.

"In some circumstances they may not have sufficient intelligence indicating extremist intent to justify continued investigation. Where they are aware that their coverage is incomplete, we recognise that the decision to stop investigating such an individual will always be difficult."

When there's enough evidence to prosecute, or of an imminent threat, they move in for the arrest.

Though MI5 found insufficient evidence in the cases of Adebowale and Adebolajo to intervene before Rigby was murdered, in many other cases they do gather enough intelligence.

UK Home Secretary Theresa May said the security services had foiled 40 planned terror attacks since 7/7 in 2005. Once MI5 and the other agencies have documented enough evidence for a conviction under anti-terror legislation, they move in and arrest those at the centre of a plot.

The government is concerned about an increased threat of terror thanks to the war in Syria and the eruption of the Islamic State. Hundreds of radicalised British Muslims have left the UK to join the fighting. The focus has turned on monitoring them when they come home.

May unveiled a raft of new anti-terror measures after raising the threat level from "substantial" to "severe".

These include letting police force terror suspects to move to another part of the country and "temporary exclusion orders" on British citizens suspected of terror activity who are trying to return home.

But MI5 and GCHQ are struggling to justify they extent of their powers in the wake of the Edward Snowden scandal. Both agencies have been accused of harvesting information illegally from the internet, something they deny.

Politicians and security services have to reconcile public distrust of anti-terror law and surveillance, privacy rights and a fight against the ever-present threat of terrorism.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.