Let Jo Cox's death reduce the hate of our MPs and improve the politics of hope

As I flew to Belfast out of Heathrow last night, one of the two TVs in the lounge was surrounded by Northern Ireland supporters cheering their team's success in the European football championships; and the other by a crowd of people digesting the horrible, horrible news that Jo Cox had been murdered on the streets of her Yorkshire constituency.

In the same space, yards apart, mingled the joy that only sport can bring alongside tragedy of unimaginable proportions for a young family, and for our politics.

I do not know if her killer is mentally ill. The mental health campaigner in me knows that the mentally ill are still more likely to be victims of violence than perpetrators.

Nor do I know whether, beyond what I read on social media, he has far right political views. The police and others will now seek to establish the facts.

There are certain inescapable realities in our political debate and culture, however, that we would do well to reflect upon as the loss of a wonderful woman and a terrific public servant sinks in, and two young children come to terms with the news her husband Brendan gave them this morning, that their Mum is dead.

The first, for all the deserved plaudits for Jo Cox in the press, is that much of our media devotes itself, relentlessly, strategically, often with wilful disregard for fact or impact on political discourse, to turning the public against its elected representatives. The expenses scandal was real, but MPs were all tarnished with the same brush, when most did no wrong.

Editors on seven figure salaries pen editorials regularly suggesting that any pay rise for MPs is a scandalous waste of public money, and the idea that they should be able to travel in comfort between Parliament and constituency, or have adequate support, an abomination. Then of course they 'all' fail to keep their promises, only care about themselves, are prepared to sell their grannies for a few votes, and have no understanding of the real world.

If these views are propagated so often, day in, day out, can we really be surprised if they take hold? If you want to bathe in warm applause, get yourself into the audience for a political panel show and shout at the politicians that you wouldn't trust them as far as you could throw them, and the ovation is guaranteed.

She fought for hope over hate, and she fought tirelessly for democratic politics as the way to change the world for the better.

There is a near nihilism about politics that will not be reversed by one day's obituaries and calls for a gentler and more mature debate and media coverage, the likes of which we heard after Labour leader John Smith died, and after Princess Diana died as well. In fact, even within the coverage today, there is a sense that Jo was an exception, rather than the rule in politics, which is a subtle way of confirming the narrative about our MPs rather than challenging it.

"Jo Cox was no normal politician," I just heard on the BBC lunchtime news. Well, actually she was. A great woman, a fantastic MP. A normal politician. The reality is most people in politics are good people who work hard and do their best according to their values. There is bad amid the good but the bulk is good. That is a reality we hear all too rarely.

The second inescapable truth – and I am conscious of the fact campaigning on the referendum has been suspended, but I feel this needs to be said – is that the current campaign has unleashed a nastiness in our debate that feels not dissimilar to some of the hatred I recall from working with Tony Blair in the city where I write this, Belfast, in what is famously the most bombed hotel in Europe, the now peaceful Europa.

I do not mean Leavers and Remainers want to kill each other. But I do mean that the campaign, ventilated by newspaper bias and distortion, social media anger, the volume of 24/7 news, and the feeling that politicians have to shout louder and louder if they want to get heard, has become too much about hate, too much about doing down opponents, not enough about politics having a strong and powerful vision of the future and thrashing out argument in a moderately civilised way.

Jo Cox stood for so much that is good in politics. She fought for women's equality. She fought in various roles for the poorest people in the poorest parts of the world. To her dying day, she was fighting for the world to face up to the reality of what is happening in Syria.

I hope that even with the short time left to the referendum itself, this can change. I hope we can hear our political leaders talking less about stats that few any longer believe (back to the nihilism of the era of disbelief) and more about what kind of country we are becoming, and what kind of country we could be.

I hope (if almost certainly in vain) that our newspapers can, just for a few days, see their role as trying to inform a confused public rather than confuse them further, and give platforms for all views, not just those that fit their own pre-ordained agenda.

Northern Ireland is to my mind the best response to those who say that politics never makes a difference. It does; and here, as I look out onto what could be just another modern Western European city, it really has. That happened because people who would normally work against each other – up to and including murder – decided there was a different way, a better way, which was rooted in dialogue and co-operation.

At least in our Tory-Labour party politics, we have never been moved to kill our opponents, as for so long the various sides did here. But the H word – hatred – is one that has been far too prevalent in the debate about our future in or out of the European Union.

People on the same side of an argument who don't want to campaign together. Best friends in the same party who have spent careers built on shared beliefs and trust now calling each other liars.

But above all, deliberate generation of a hatred of outsiders, as an issue as complex and difficult as immigration is seen not as a problem to be addressed but an issue to be exploited.

Emotion must always have its place in politics. It is about big things, big challenges, big differences of opinion. But the debate around those challenges cannot only be about emotion. There must be a basis in fact and rational analysis for arguments.

Jo's very last tweet said this: "Immigration is a legitimate concern. It is not a reason to leave the EU.'

Yesterday, Nigel Farage launched a poster. It had a picture of a massive queue of dark-skinned people leaving Syria and heading to Slovenia. The suggestion was clear – these people are coming here, it is the EU's fault, and only a Leave vote on 23 June could stop them. It was horrible, disgusting, more 1930s than 2010s. If Farage's condolences tweet last night is to mean anything, he should remove the poster, and apologise.

But this goes beyond the fringe that Farage used to represent. As Polly Toynbee said in the Guardian today, members of the Cabinet and other leading Tories like Boris Johnson have played the Farage game with zeal. Polly puts it well: "When politicians from a mainstream party use immigration as their main weapon in a hotly fought campaign, they unleash something dark and hateful that in all countries always lurks not far beneath the surface."

The entire campaign, it seems to me, has been founded on generating anti-feelings – anti-elite, anti-'expert', anti-politics, anti-fact in favour of anger and emotion.

Jo Cox stood for so much that is good in politics. She fought for women's equality. She fought in various roles for the poorest people in the poorest parts of the world. To her dying day, she was fighting for the world to face up to the reality of what is happening in Syria, and do more to address it.

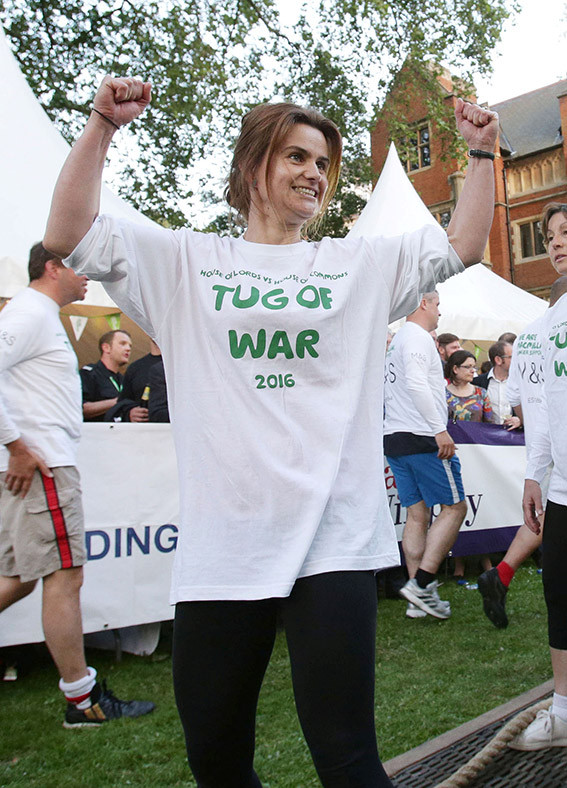

She fought for progressive values and progressive causes which have lost a great champion. She fought for Britain to be active and engaged in the world and she fought for a sensible, rational, fair, humane approach to immigration. She fought for constituents who have lost a fantastic MP. She fought for hope over hate, and she fought tirelessly for democratic politics as the way to change the world for the better.

If her death is to have any value whatever – which right now is hard to see – let a genuine and lasting appreciation of politics and politicians as a force for good be part of her legacy.

Alastair Campbell is a British journalist, broadcaster, political aide and author, best known for his work as Director of Communications and Strategy for Prime Minister Tony Blair between 1997 and 2003. He is the author of two books on mental health and is an ambassador for Time to Change.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.