London riots 5 years on: If we don't listen to the deprived, our streets will erupt again

Brexit debates revealed the same schisms and disenchantment as in 2011.

At five pm on this day, exactly five years ago, a small, dignified, desolate, crowd gathered outside Tottenham Police Station. Mark Duggan, a mixed-race, local man, had been shot dead by the police the previous evening. His friends and family wanted to know the truth and get justice.

Duggan, 29, a father of four, was in a minicab when he was killed. He had a criminal record but no serious convictions. Police said he'd pulled out a gun, a witness disagreed. A gun was found twenty feet away from the vehicle. An inquest in 2014 exonerated the police. An appeal is likely.

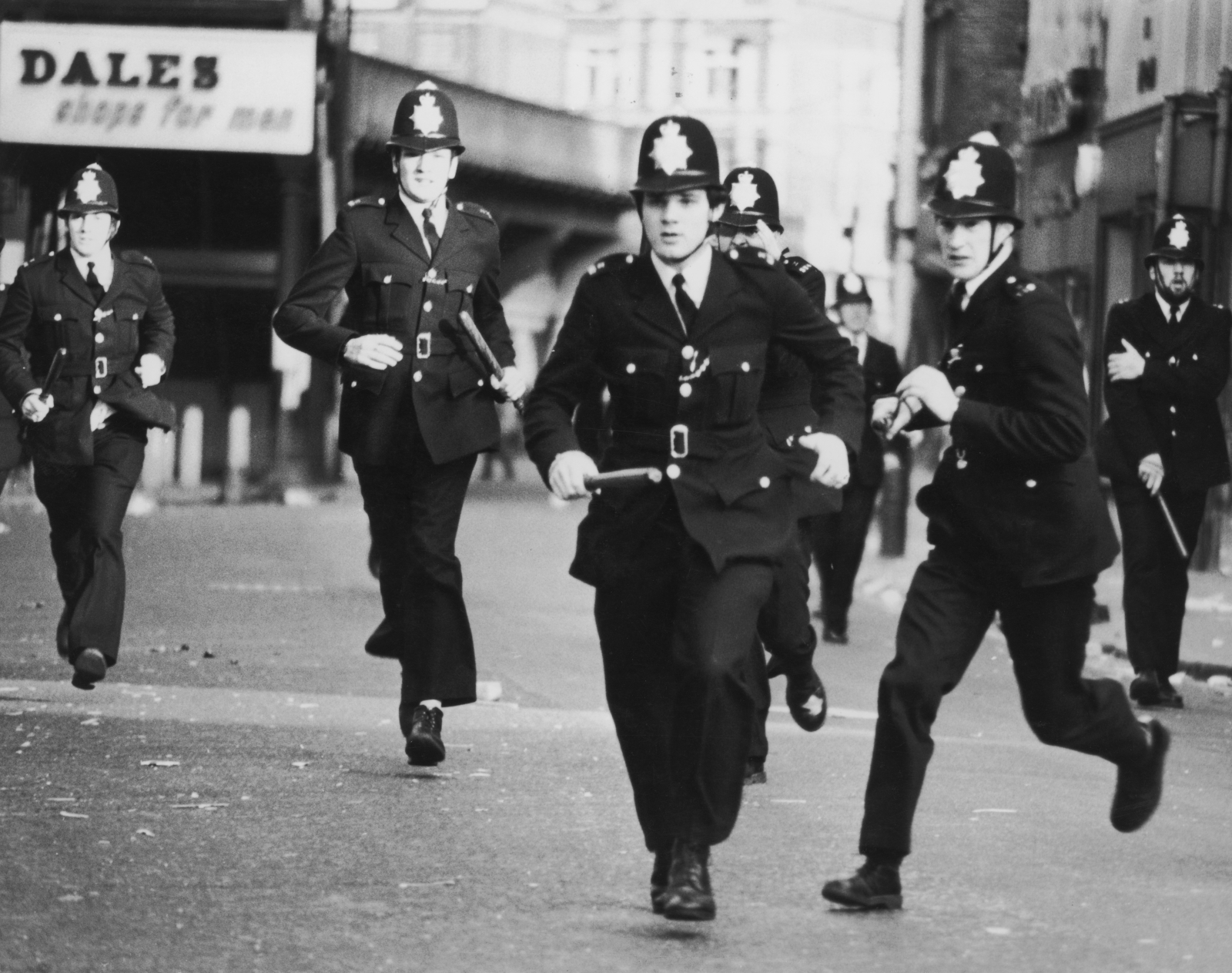

Three and a half hours after this demo, wild riots erupted across parts of London. It was a Friday. By Tuesday, looting, destruction and violence had spread to the suburbs and most other towns and cities.

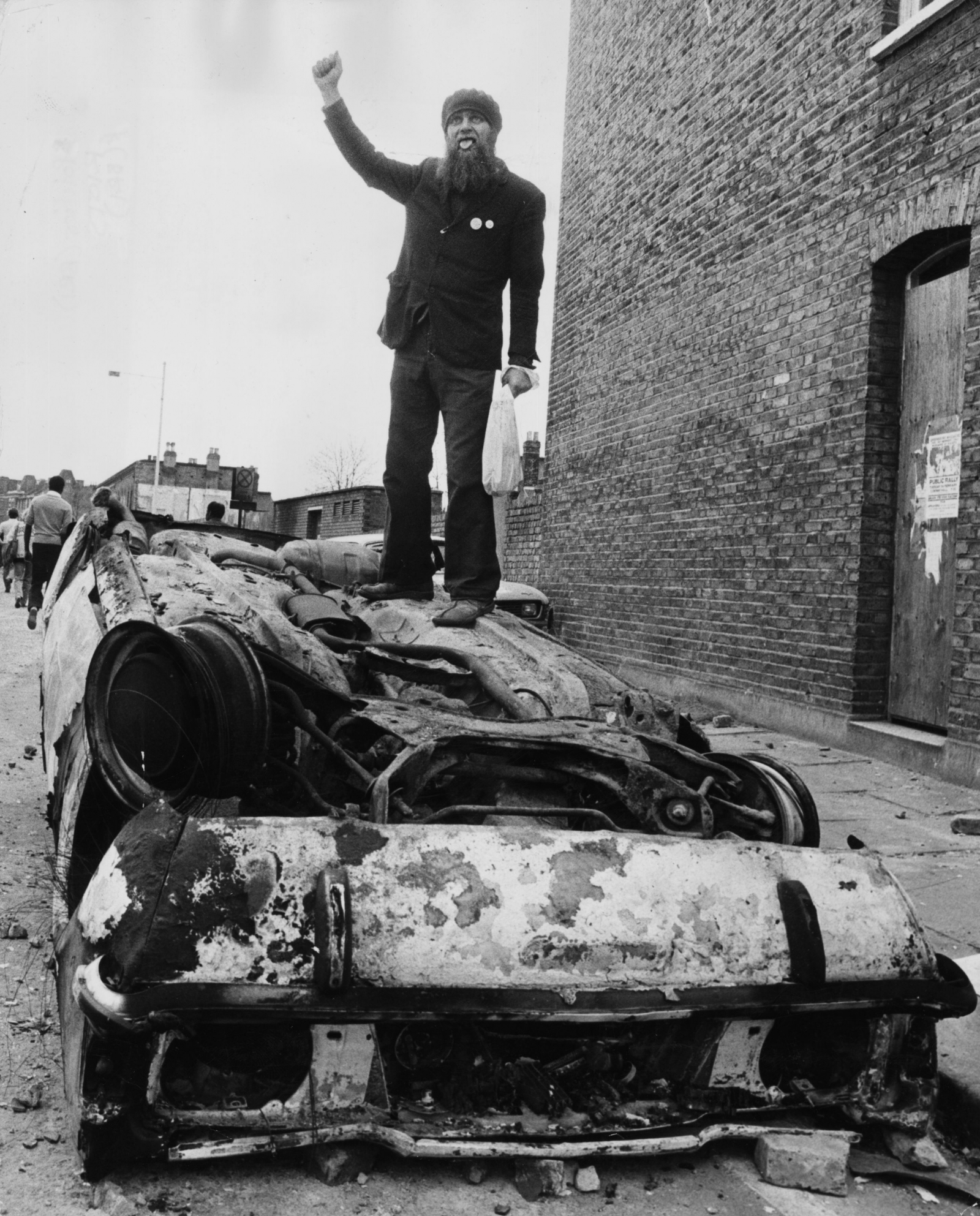

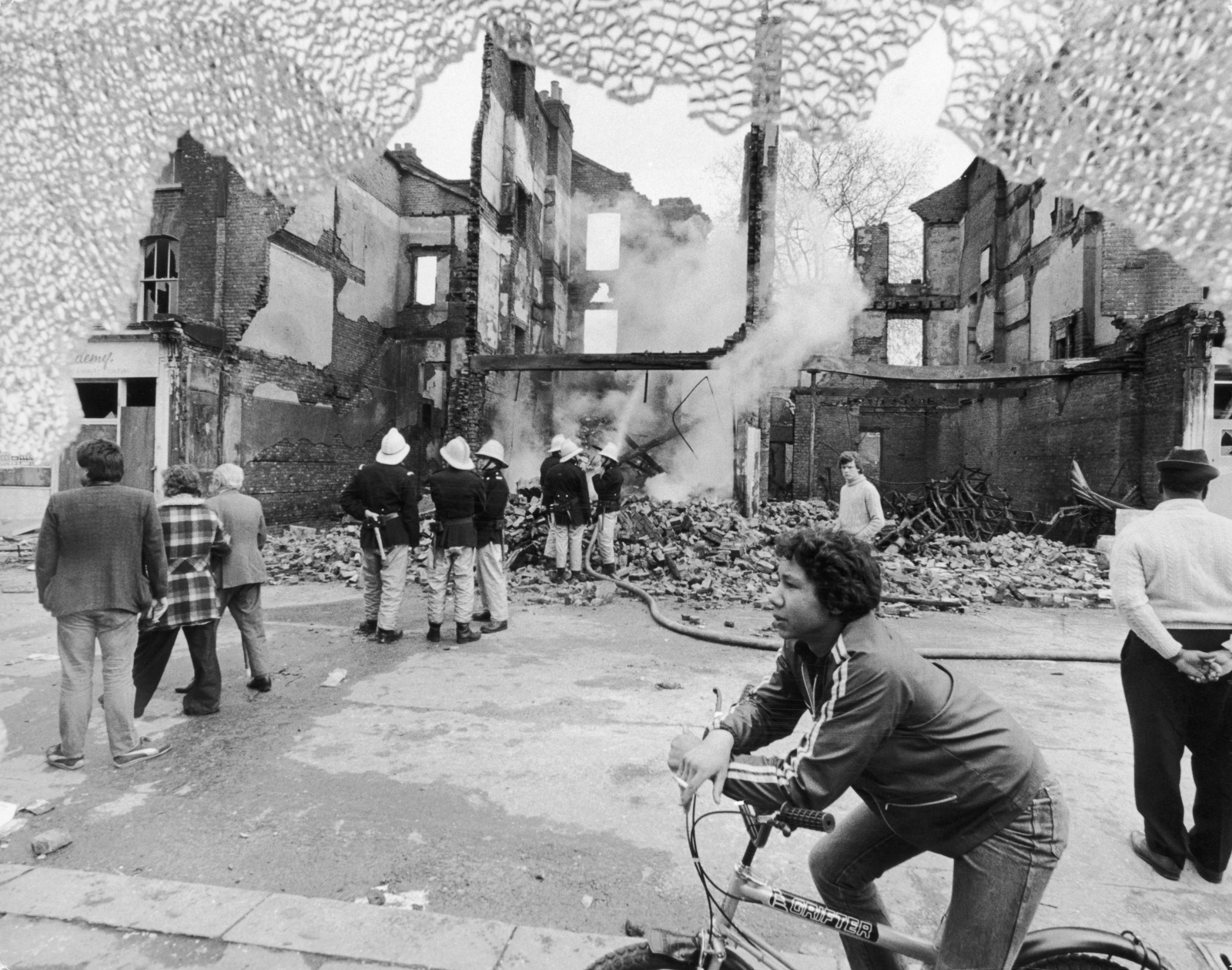

Established businesses were torched. England seemed to be burning with rage and engulfed by anarchy. Police forces were overwhelmed; Alex Salmond dispatched 250 officers down to the Midlands to help quell the mayhem; courts were kept open day and night, cells were overflowing.

In my part of west London, shop windows were kicked in, properties torched. Our soft, secure little lives were overturned. Middle class residents would have been less stricken by an actual earthquake. One local woman, went on TV, wept and shrieked: 'Who are these ruffians? What are they like? I never knew we had such ignorant people in this country'. (Remember these questions. I return to them later).

England seemed to be burning with rage and engulfed by anarchy.

By the time order was restored, around 1,200 people had been arrested and five men had died. Parliament was recalled. Michael Gove, then education secretary, attributed the disturbances to 'a culture of rootless hedonism', a culture, one could argue, was nurtured by his fellow Tories and New Labour.

Andy Burnham and Ed Milliband - the former party leader - condemned the wanton vandalism. Cameron pronounced that the unrest was caused by "criminality, pure and simple". His heroine, Margaret Thatcher understood that these moments are never "pure and simple".

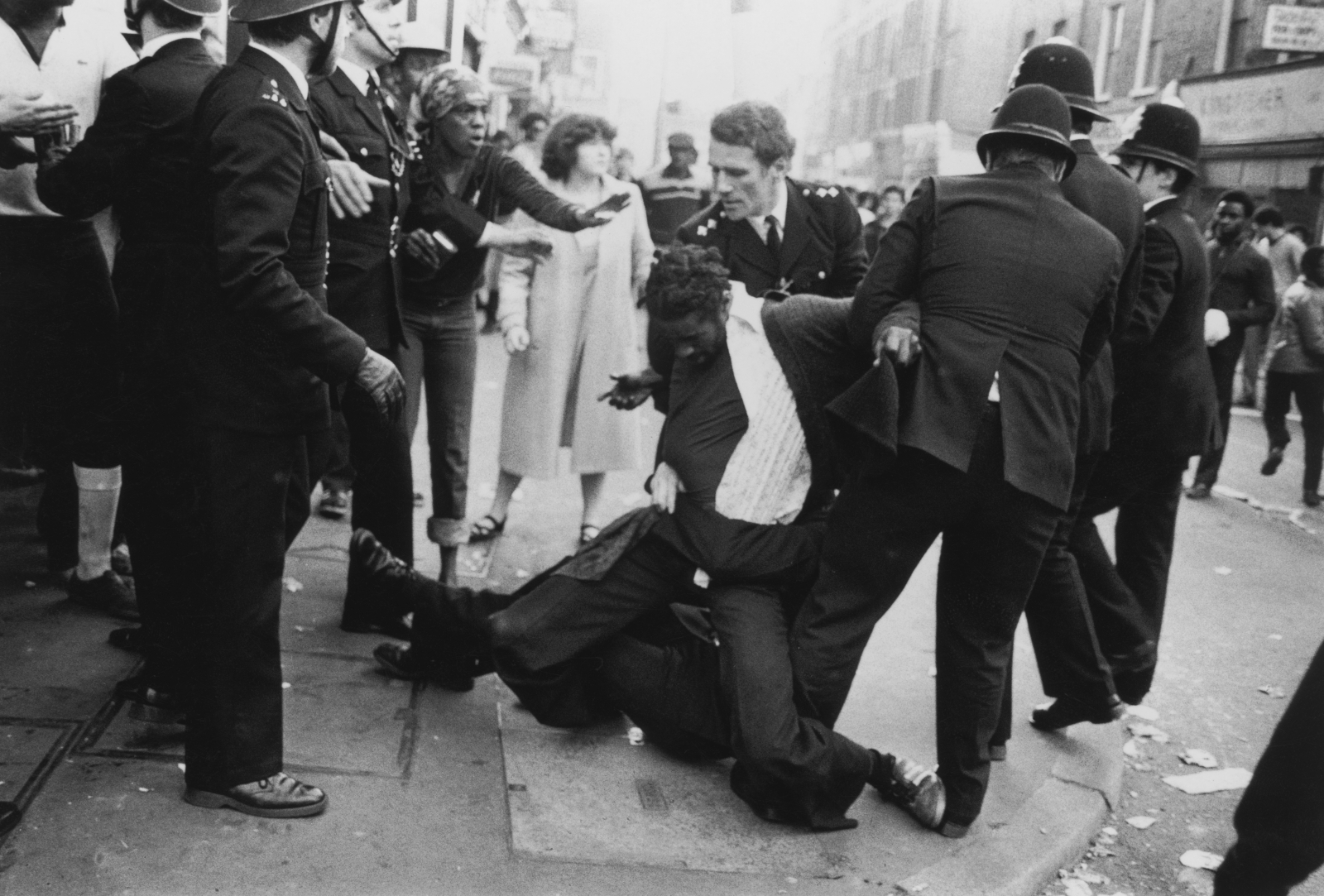

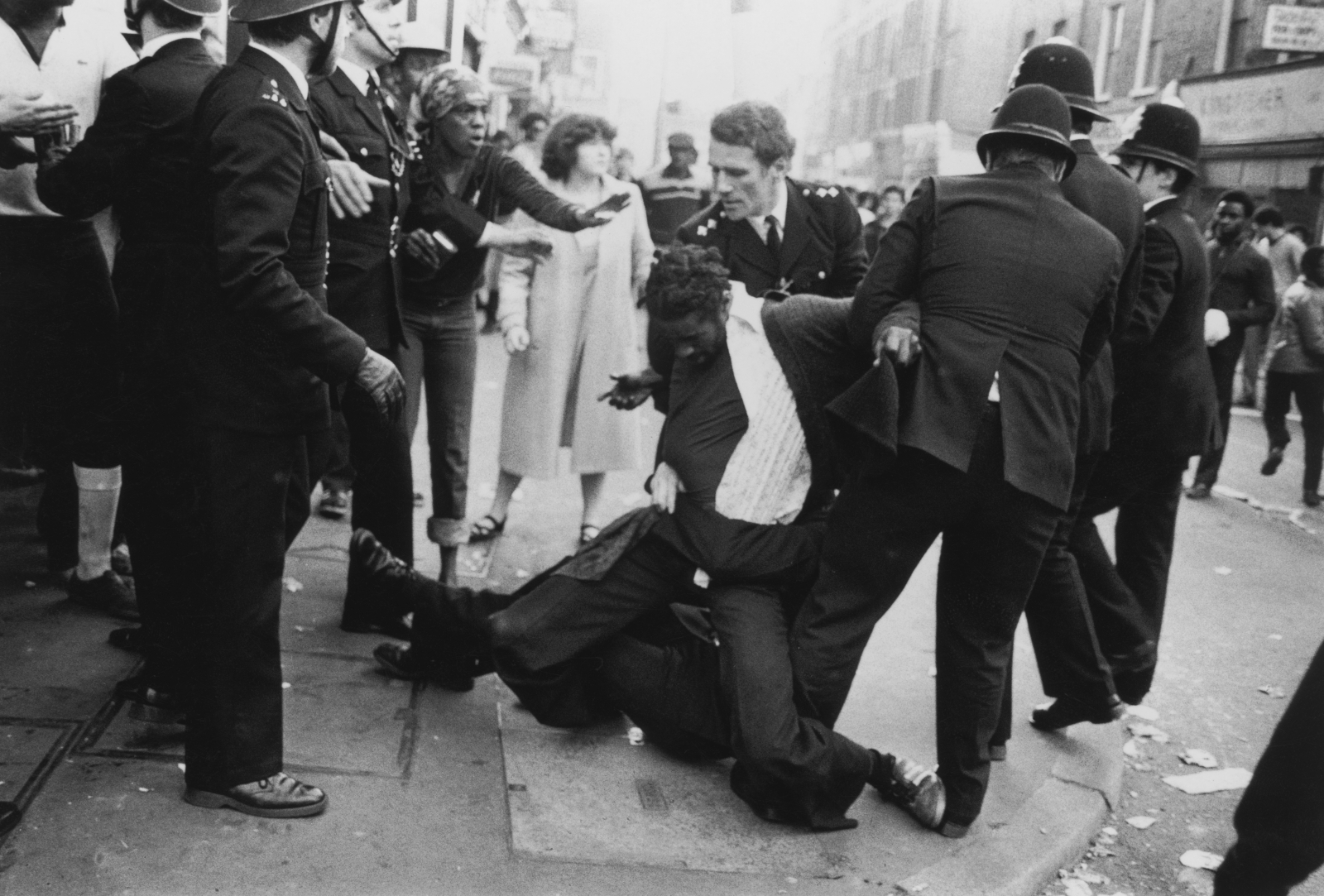

In 1981, ferocious riots broke out first in Brixton, then Tottenham, Liverpool, Bristol and other conurbations. The Iron Lady took charge, responded robustly. But she understood the troubles were symptoms of serious social and economic ills. She met concerned individuals from all backgrounds.

She appointed Lord Scarman, a fair and respected judge to investigate the causes of the Brixton disturbances. He recommended urgent action to tackle racial disadvantage and insensitive policing. Some of those policies were implemented.

She got Michael Heseltine to go into deprived areas and produce a workable regeneration programme. Heseltine's plans turned round some of the most hopeless of northern towns and cities. Liverpool, for example, was born again and retains its verve and ambitions.

Over those heady days, many took stuff they could never have been able to buy, while others enjoyed being consumer mutineers, snatching goods simply because they could.

Unfortunately, after the 2011 riots, our political leaders could not rise above hectoring and machismo. Milliband did suggest the deeper causes needed to be examined, but he didn't push it for fear of being seen as pathetic and weak. As Alan Rusbridger, erstwhile editor of The Guardian, observed, "after one of the worst bouts of civil unrest in a generation", there was no inquiry into the roots of the troubles.

In subsequent months, reports were produced by The Guardian, and The London School of Economics and other academics. They contain stark findings and warnings. Black people complained bitterly about alleged police racism. (Theresa May has spoken bluntly about this issue). Even more disturbingly, the riots revealed a nation which was divided and shattered. Mistrust and alienation had grown since the 1980s. So too poverty.

Around 62% of those who went out to loot, vandalise buildings and terrorise citizens were unemployed and impoverished. (Government analysis shows 64% came from the poorest fifth of urban areas). Over those heady days, many stole items they could never have afforded, while others enjoyed being consumer mutineers, snatching goods simply because they could.

Bryn Phillips, one of the rioters, wrote recently about how angry he had been about phone hackers, bankers, MP's expenses, corrupt police, rising inequality, unbridled market forces, a system that wastes lives and trashed hopes. The government did nothing to make such people feel they mattered or belonged.

Brexit debates, often more full of heat than light, revealed the same schisms, the same disenchantment. Millions of those who voted to leave the EU found a way to be heard and noticed. Those who wanted to remain asked, "Who are these rough necks?" "What are they like?" "Never knew we had such ignorant people in our country."

Belatedly, politicians are rushing around promising to listen, to assuage the negative effects of globalisation. The PM wants responsible capitalism and better workers' rights. Let's hope they mean it and can deliver. If they don't, the streets will erupt again and we may get Ukipers joining urban youth to form an unstoppable alliance. Imagine that if you can.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.