Meet Hope – the magnificent blue whale who replaced Dippy to guard the Natural History Museum

IBTimes UK took a tour around the transformed Hintze Hall, the old home of Dippy the dinosaur.

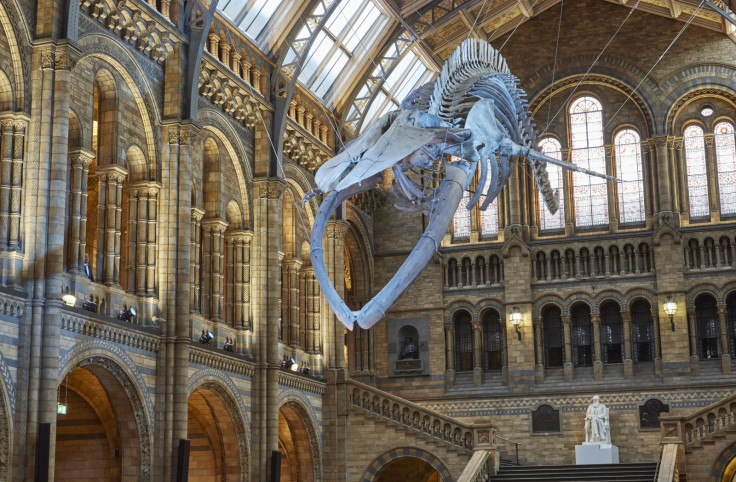

The main entrance hall of the Natural History Museum is opening its doors to the public tomorrow after six months of closure. The Hintze Hall has been undergoing a transformation. It was the home of the cast of a diplodocus dinosaur, fondly known as Dippy. Now its new central occupant has been revealed: a blue whale that has come to be known as Hope.

The blue whale skeleton stretches for 25 metres from nose to tail, hanging high above our heads in the hall. The whale's jaws are wide open in the act of feeding and the spine is arched, poised for a dive into the deep ocean. The tip of the whale's nose will hang just a few metres above visitors' heads.

Unlike Dippy, Hope is not a plaster cast but an original, complete skeleton. The female blue whale washed up in Wexford, Ireland, on 25 March 1891. She's thought to have been just 10 years old when she died.

At the time, the Natural History Museum bought the specimen for a grand total of £250. The skeleton was shipped back to London, where the museum came up against a problem. There was no gallery large enough to accommodate the skeleton apart from the Hintze Hall – which was occupied by a sperm whale in the 1890s and 1900s. The whale was kept in storage before going on display in a specially built gallery, where she was eventually joined with several other whales.

A long journey

Now, Hope has completed her painstaking and complex journey to the Hintze Hall.

"It was extremely tricky to bring her down off that display, she was several metres in the air," Lorraine Cornish, head of conservation at the Natural History Museum, told IBTimes UK.

First of all, they had to figure out just how much the whale skeleton weighed. As expected, it was a lot: just the bare skeleton weighed about 3 tonnes. The next task was to bring the skeleton down – all 221 bones – which took several months.

"The skull alone is 6 metres long, consisting of 46 bones which are fused and semi-fused," said Cornish. "They are extremely delicate."

The task was made more complicated because the specimen was an antique. The whale had been hanging in its previous hall for more than 80 years before the manoeuvre.

"There were some cracks," said Cornish. "There were some areas that we were quite concerned about."

The next 10 months were spent strengthening the bones, and building a brand new metal framework, or armature, to hold them. The whale's previous armature was a stiff Victorian arrangement in a flat, straight line. For the modern exhibition, the whale was to take on a much more ambitious position.

"We wanted to have her in a life pose. So she's diving down in a lunge-feeding pose with her giant mandibles open," Cornish said.

Then at last the whale was slowly winched up into her present position, to hang above visitors' heads.

"It was quite nerve-wracking, I have to say."

Why a whale?

The new specimen's name gives a clue to why it was chosen as Dippy's successor in the Hintze Hall.

"We want to get people thinking about the future of the natural world," said Ian Owens, director of Science at the Natural History Museum. "The skeleton is a great way into doing that, while also having a really spectacular display to show people."

Blue whales are one of the great ongoing success stories of conservation. About 50 years ago scientists and environmental activists began campaigns to ban international commercial whaling. Global populations were plummeting and species including the blue whale were at a high risk of extinction.

"We want to give people an example of where a decision had a really good, a really hopeful effect," said Owens. "With this blue whale, it symbolises humans stepping in to conserve the great whales in the 1960s, taking them from probably about 400 individuals in the world, probably very close to the brink of extinction, all the way through to 20 to 25,000 now – the beginnings of a viable population."

Even with this success, the blue whale remains an elusive species. Much of its biology and behaviour remain unknown because they are simply too difficult to access and study. But this picture is gradually changing.

"It's still an area of very active research. Even from this blue whale skeleton, we're still finding out new things about its life with new genetic and chemical techniques we can use," Owens said.

But one question remains – will Hope gain the iconic status that Dippy has enjoyed for the past 38 while it occupied the hall?

"We hope people are really excited to see Hope," said Owens. When people come through that front door, we really want them to think 'Wow, that's an amazing specimen, I want to know more about it'.

"So we hope it will become an icon in the same way. But we're not trying to get Dippy out of our lives. The fact we've taken Dippy out of here, and it's going on a tour around the UK."

Dippy has set off on a tour of museums in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, and will eventually find a new home outside in the grounds of the museum.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.