Moderna COVID-19 vaccine enters final stage trial this month

The upcoming trial will recruit 30,000 participants in the US, with half to receive 100 mg dose, and the other half to receive a placebo.

US biotech firm Moderna said Tuesday it would enter the final stage of human trials for its COVID-19 vaccine on July 27, to test how well it protects people in the real world.

The announcement came as the results from an earlier trial intended to prove the vaccine was safe and triggered antibody production were published.

The upcoming Phase 3 trial will recruit 30,000 participants in the US, with half to receive the vaccine at 100 microgram dose levels, and the other half to receive a placebo.

Researchers will then track them over two years to determine whether they are protected against infection by the virus. Or, if they do get infected, whether the vaccine prevents symptoms from developing.

If they do get symptoms, the vaccine can still be considered a success if it stops severe cases of COVID-19.

The study should run until October 27, 2022, but preliminary results should be available long before.

The announcement came shortly after the New England Journal of Medicine published results from the first stage of Moderna's vaccine trial, which showed the first 45 participants all developed antibodies to the virus.

Moderna is considered to be in a leading position in the global race to find a vaccine against the coronavirus, which has infected more than 13.2 million people and killed 570,000.

But scientists caution that the first vaccines to come to market may not be the most effective or safest.

Moderna had previously published "interim results" from the first stages of its trial, called Phase 1 in May.

The early results were called "encouraging" by Anthony Fauci, director of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which is co-developing the vaccine.

But some in the scientific community said they would reserve judgment until they saw the full results in peer-reviewed form.

According to the paper, 45 participants were split into three groups to test doses of 25 micrograms, 100 micrograms and 250 micrograms.

They were given a second dose of the same amount 28 days later.

After the first round, antibody levels were found to be higher with higher doses.

Following the second round, participants had higher levels of antibodies than most patients who have had COVID-19 and gone on to generate their own antibodies.

More than half the participants experienced mild or moderate side effects, which is considered normal.

The side effects included fatigue, chills, headache, body ache and pain at the injection site.

Three participants did not receive their second dose.

They included one who developed a skin rash on both legs, and two who missed their window because they had COVID-19 symptoms, but their tests later returned negative.

Amesh Adalja, an infectious diseases specialist at Johns Hopkins University, said it was encouraging that the participants developed high levels of an advanced class of antibodies.

He added, however: "You have to be very limited in how much you can extrapolate from a phase one clinical trial, because you want to see how this works when a person is exposed to the actual virus."

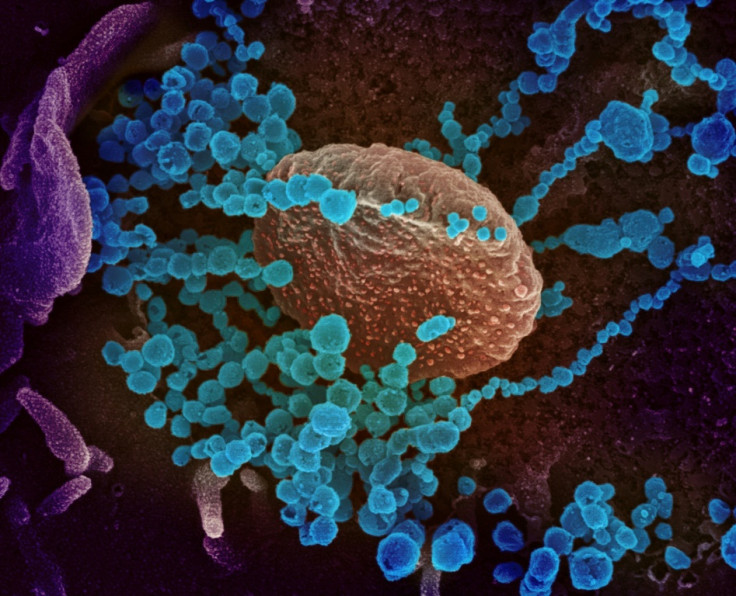

The Moderna vaccine belongs to a new class of vaccine that uses genetic material -- in the form of RNA -- to encode the information needed to grow the virus's spike protein inside the human body, in order to trigger an immune response.

The spike protein is a part of the virus that it uses to invade human cells, but by itself the protein is relatively harmless.

The advantage of this technology is that it bypasses the need to manufacture viral proteins in the lab, helping to ramp up mass production.

No vaccines based on this platform have previously received regulatory approval.

Early work using this technology backfired by making hosts more, not less, susceptible to infection, David Lo, a professor of biomedical sciences at University of California Riverside told AFP.

"One of the things we certainly want to look out for is whether there is a long term effect where the immune response... potentially develops an immunologic tolerance which would actually be detrimental to protection," he said.

Copyright AFP. All rights reserved.

This article is copyrighted by International Business Times, the business news leader