Moon Landing 45th Anniversary: Who Is Michael Collins The Forgotten Astronaut?

A look at Apollo 11's third man

Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin are two names that will echo through human history as the first two men to walk on the Moon. In school we're told about the Apollo 11 mission and shown footage of Armstrong's iconic small step and listen to his iconic quote.

It is no secret that a third man was present on the Apollo 11 mission, but that hasn't changed the fact that Michael Collins will forever be an undeserved footnote on history. As Aldrin and Armstrong trotted along the lunar surface, it was Collins who orbited alone above it waiting for their return.

On the 45<sup>th anniversary of Apollo 11's success, we want to shine a spotlight on the forgotten hero of one of mankind's greatest achievements.

Born in Rome on 31 October 1930, Collins never really settled as a child, living in Oklahoma, New York, Texas, Virginia and Puerto Rico before finally settling to attend school in Washington DC when the US entered World War II.

Following in the footsteps of his father, brother, uncles and cousin, Collins elected to join the armed services, joining the United States Military Academy where he graduated with a degree in science in 1952.

Collins then joined the United States Air Force where he flew F-86 jet fighters in France before becoming test pilot based in California, and soon after applying to become an astronaut in Nasa's space programme. His first and second applications were unsuccessful, but it proved to be third time lucky for Collins

Collins served as a backup crew member on the Gemini 7 mission but wouldn't take part and enter space until Gemini 10, a three-day mission which went off without a hitch. The Apollo programme soon followed, with Collins proving an integral part until the famed Apollo 11 mission, which was his second and final space flight.

That almost never happened however. The year prior to that mission Collins suffered a major injury that could have wrecked his career. Problems with his legs were revealed to be the result of a cervical disc herniation which required two of his vertebrae to be fused together and forcing him to wear a neck brace for three months.

He recuperated quickly, but not quickly enough to avoid being pulled from the Apollo 9 mission. Collins was replaced by Jim Lovell prior to the crews of Apollo 8 and 9 being switched. Should he have made it onto Apollo 8, Collins would have been on the first space craft to leave Earth's orbit and enter that of the Moon.

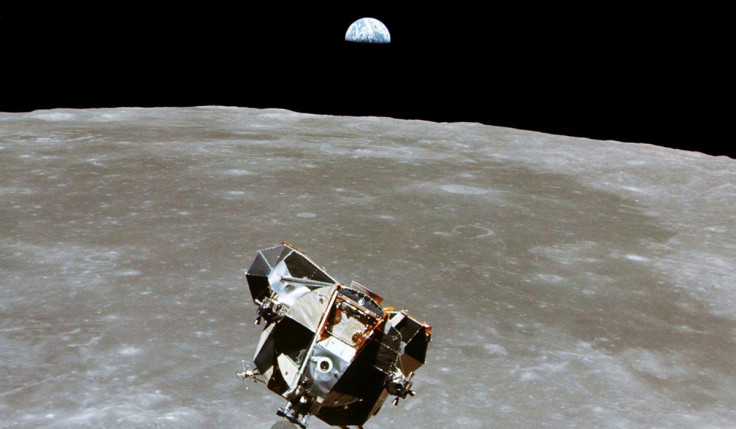

Apollo 11 was just around the corner however, and as we know Collins made it to that fateful mission. As pilot of the command module Columbia, Collins never reached the lunar surface, instead orbiting for an entire day as Armstrong and Aldrin carried out their mission at the Sea of Tranquillity.

In a note written at the time (revealed by The Guardian) Collins wrote of his great fear ahead of and during that mission. "My secret terror for the last six months has been leaving them on the Moon and returning to Earth alone; now I am within minutes of finding out the truth of the matter."

"If they fail to rise from the surface, or crash back into it, I am not going to commit suicide; I am coming home, forthwith, but I will be a marked man for life and I know it."

In an interview coinciding with the 40<sup>th anniversary in 2009, Collins was asked whether he felt lonely orbiting the Moon.

"Far from feeling lonely or abandoned, I feel very much a part of what is taking place on the lunar surface," he said. "I know that I would be a liar or a fool if I said that I have the best of the three Apollo 11 seats, but I can say with truth and equanimity that I am perfectly satisfied with the one I have.

"This venture has been structured for three men, and I consider my third to be as necessary as either of the other two."

It certainly was. Even if history will consign him as an undeserved footnote, Collins played the most crucial part in the Apollo 11 mission's second most incredible feat: getting Armstrong and Aldrin off the Moon and safely back to Earth.

Following the mission its crew embarked on a 45-day world tour. Soon after Collins left Nasa to accept a position at the United States State Department. Clearly not enamoured with a political life Collins quit after a year to become director of the US National Air and Space Museum, where he stayed until 1978.

In the years since Collins has written a number of books, including an autobiography, a historical book about the American Space Programme, another about potential expeditions to Mars and a children's book about his experiences.

He currently lives in Florida with his wife, who he met at the start of his career in the military. Together they have three children.

Collins' contributions to the history of space travel will be well-remembered, if not as well-remembered as his famous colleagues. Perhaps his most memorable offering however will be that of the Apollo 11 mission badge (right), which he designed.

To finish, here is a quote from Collins, provoked by a question about his strongest memory from Apollo 11.

"If the political leaders of the world could see their planet from a distance of 100,000 miles their outlook could be fundamentally changed," he said. "That all-important border would be invisible, that noisy argument silenced. The tiny globe would continue to turn, serenely ignoring its subdivisions, presenting a unified façade that would cry out for unified understanding, for homogeneous treatment.

"The Earth must become as it appears: blue and white, not capitalist or Communist; blue and white, not rich or poor; blue and white, not envious or envied."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.