Most Britons don't have a religion anymore - it's time our institutions caught up with them

Religion continues to permeate UK politics and society, even as a majority of people ditch faith.

The case for secularism does not lie in the figures. Even if everyone in a country said they shared the same religion, fundamentalists would not have the right to impose their views on moderates. But the news that non-religious people are apparently in the majority in Britain is a reminder that our major institutions – and public life more broadly – is out of step with the British public.

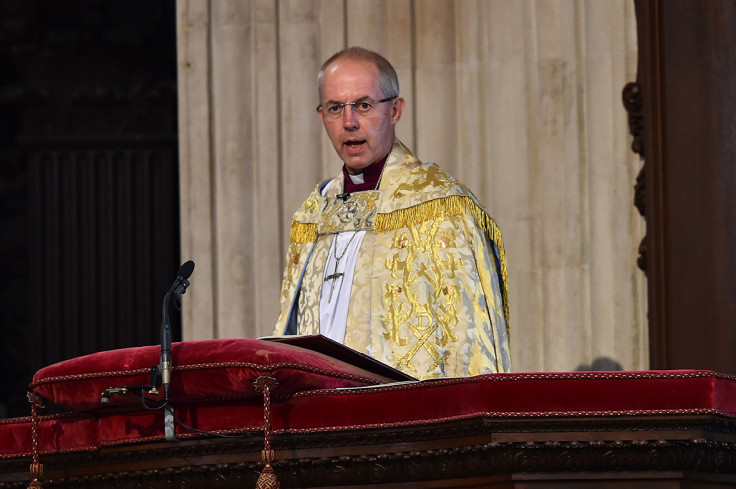

In some ways the excessive deference we give to religion is blatant. The Church of England is established and 26 bishops still have a constitutional right to a place in the House of Lords. The government asks religious groups to run our publicly-funded schools. Christian prayers are said as part of official parliamentary business.

In other ways it is more subtle. Drayton Manor Park in Staffordshire changed its entry policy to allow Sikhs to carry knives. The Church of Scotland's moderator gave an official blessing to the new Queensferry crossing. It has emerged that thousands of state primary schools are incorporating the hijab into school uniform codes for pre-pubescent girls. These are just the latest instalments in an ongoing series of concessions to the religious lobby.

In response to the new figures several commentators have stressed the good that people do in the name of religion and expressed concern about what may come next. Secularisation, the argument goes, leaves a vacuum which could be filled by something particularly intolerant: extreme nationalism, perhaps, or radical Islam.

In the current climate, fear of these forces is understandable. But one of the striking elements of the politics of our times is its anti-secular character. Religion is far from being a private affair: it is a major political dividing line.

Nearly six in 10 Christians voted to leave the EU; seven in 10 Muslims voted to remain. In 2016, all five Tory leadership contenders were outspoken Christians, and during London's mayoral election both detractors and supporters seemed endlessly focused on the fact that Sadiq Khan was a Muslim. No wonder the magazine Christian Today said a "re-awakening" was taking place, where politicians increasingly felt the need to share their religious views with the rest of us.

Religion is also behind rising intolerance abroad. More than four in five white evangelicals voted for Donald Trump to become US president. Trump got a higher proportion of their votes than Mitt Romney, John McCain or George W. Bush before him. And evangelical advisers continue to prop up the Trump administration even as others, for example from the world of business, desert him. India is experiencing a rise in Hindu nationalism under Narendra Modi. The orthodox church is one of Vladimir Putin's most important backers. Islamic fundamentalism continues to claim and ruin lives around the world.

And where the left has erred, it has been because it has embraced moral relativism and rejected secularism. Free speech is viewed as an expendable luxury. Campaigners for Islamic reform, or the rights of women or gay people in the Muslim world, are smeared. The current Labour party leader's history of allying with Islamists is explained away.

Over the centuries the religious lobby has not accepted the position of women, gay people or science – among many other things – easily. And in a multi-faith era, they hold the door open for each other's intolerance. In 2008 Rowan Williams, then the Archbishop of Canterbury, agreed with a questioner who asked him if the application of sharia was an "unavoidable" concession needed for social integration. After the massacre at the Charlie Hebdo offices, the Pope bought into the narrative that the cartoonists had brought it on themselves, saying: "Curse my mother, expect a punch."

Too often we accept this, while convincing ourselves we are being moderate or 'respectful'. We have a religious conservatism of our own, the argument goes, so we must allow others their equivalent. When New Labour decided it was too hard to take on the Church over Christian faith schools, Charles Clarke created schools for other faith groups.

But this approach has entrenched segregation even further and allowed religious groups to claim special rights that the rest of us do not have. Schools are allowed to choose their intake based on the faith of parents. The blasphemy law may have been officially repealed in 2008, but an Olympic gymnast can be banned for two months and forced into a grovelling apology for having a laugh about Islam at a wedding. Religious groups are granted tax breaks with precious few questions asked about the public good they are doing.

Now the evidence suggests we are not even deferring to a majority. But even if we were, it would not be the point. Societies can only cohere when they have a set of principles and laws to unite around. Secularism, when defended consistently, provides a framework of rights and responsibilities for all; a commitment to reason, open-mindedness and free enquiry; and an appreciation that our freedoms end when others' freedoms begin.

There is plenty of room for reasonable disagreement about where the margins of these principles lie. But only fanatics oppose them outright. It is up to the rest of us to stand up to them and call their stance out for what it is.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.