My dad went to prison for his gambling double life - and we were left with the £500,000 debt

We are on the brink of losing our family home.

Gambling has been a staple of British society and a fabric of our social lives for hundreds of years. Horse racing is a respected British pasttime as is 'having a flutter'.

The government allowed gambling from the 1600s amongst the aristocracy, but for the working classes these activities were effectively illegal until the 1960s. Gaming houses were one of the main social venues in London and the spa towns in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Its lotteries funded many of the country's main public buildings, such as the British Library. During this period Bath became a social centre for gambling as an Act enabled under Henry VIII still banned the lower classes from gambling except at Christmas time.

A number of Acts between 1710-1745 were targeted at the poor through the high monetary limit they put on banning gambling debts. But it was not until a Royal Commission sat in 1960 that gambling became available to the mass public under the Betting and Gaming Act, albeit in a heavily regulated way. Gambling thus became more widely legalised in the 1960s, under supervision.

Until 2007, advertisements for gambling were very restricted.

However the Gambling Act of 2005 changed this.

Nowadays you can simply pick up your smartphone, attach your credit card to an online account from any one of the dozens of operators vying for your business and empty your bank accounts at the click of a button.

I know from first-hand experience that gambling is not always just a harmless pastime. Research from the University of Cambridge shows that there is a link between gambling activity and endorphin activity in the brain. This means that for some, gambling behaviour can cause a reaction similar to a drug or alcohol addiction.

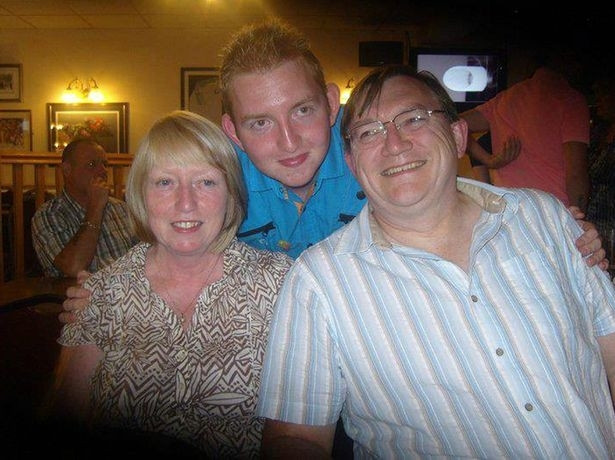

In April 2014, my father, a respected accountant and company director, walked into the living room and told our family he was off to court the next day. His 'weekend training course' was actually a trip to see a judge. He did not reveal the reasons behind the visit, but said it was related to a matter from a company he used to work at and assured us he was in no trouble.

The next day he did not return home. His solicitor phoned home to tell us that our father was in the back of a van on his way to prison.

He would serve a two-year sentence in jail. The local newspaper's front page the day afterwards explained the whole story. My dad had been gambling, way beyond his means.

He had been stealing money from his employers to pay for his addiction through re-invoicing his wages to the tune of £50,000 and got caught.

This was heartbreaking, in fact I think my heart must have stopped at the time, along with my mother's. We both sat in our front room with the newspaper in our hands and cried. We had no idea what to do. There is no number you can call to get help and very little provision to help families through such events. Our father had been taken from us and we had been left with debt, uncertainty and a huge feeling of betrayal.

We quickly discovered through debt collectors' letters that my dad had concealed our financial situation at home was dire. The house had been remortgaged over-and-above its real value to pay off debts. My father had around £500,000 of other debts alongside his stealing and had been gambling pretty much every waking second in an attempt to win back the losses.

My mum is retired and I also have two brothers at home. As a young 21-year-old at the time I had to become the 'man of the house', call the debt collectors, pay the mortgage and help my mum feed the family all from my one wage. I had to grow up quickly. This tragedy left me no time to breathe or even collect myself. I still feel as though the mental impact of it has yet to fully hit me.

I have flashbacks often, nightmares and have been taking anti-depressants for the past three years just to try and live a normal life. The truth for all of is that life will never be normal again. We are on the brink of losing our home; my mum is distraught, we are all still suffering.

Many will look at this sad story and ask how, as a family, we had no idea. It's simple - his gambling was predominantly online. When we thought he was working or completing late night emails, he was gambling away every penny we thought we had. Gambling away my inheritance, for instance. His last bet was on the day of the court hearing itself.

The Gambling Commission has just released a new report showing that over two million people are addicted to gambling. This has grown since their last report. There has also been a sharp rise in the number of younger gambling addicts. Again, this figure has grown a third since their last report a few years ago.

The Gambling Commission regulates gambling operators in the UK and operators do donate approximately £6m yearly towards mitigating the effects of gambling-related harm, including funding some counselling services.

I know I am not the only one who thinks this could be strengthened. I've talked to government ministers, gambling operators and addicts themselves to try and work out what's missing which is causing stories like my father's to be far from unique.

Last week, 888.com, one of online gambling's largest operators, was fined £7.8m by the Commission for failing to safeguard its customers. Those who self-excluded themselves from the site were still able to bet due to a 'technical glitch' and the company aggressively marketed to them too.

My dad was one, he was in prison and was marketed to by this company and its affiliates. Expensive text messages were sent to his mobile phone at home and it took me several attempts to get the company to stop them. I do not understand why it should be so hard to remove yourself from these sites. Getting an addict to admit they have a problem and remove themselves anyway is such a hard process.

I personally think the true figure measuring the number of gambling addicts in this country could be much higher.

Recently the FA cut its sponsorship ties with gambling operators due to worries over insider betting. This is a good move, but the close association between major sports operators and betting companies has much deeper effects on society.

Young people at sports games get acclimatised to betting and betting companies from a very young age. Sports games on TV are top-and-tailed with betting endorsements and gambling advertising in general has increased by some 600% (Ofcom, 2013) in recent years.

Tim Miller, the chief executive of the Gambling Commission, said last week: "The pace of change to date simply hasn't been fast enough – more needs to be done to address problem gambling."

The UK's leading gambling charity GambleAware, which funds the UK's only dedicated gambling addiction clinic in London, repeated calls for the industry to increase its funding for addiction treatment to £10m.

I think it is now time for gambling to become a much less prevalent pasttime in the lives of young Britons.

It can and should always be a safe, entertaining pasttime - not a booming industry which is producing a growing number of collateral damage case studies like my dad's.

Adam Bradford, 24, is a young social entrepreneur and CEO of social change agency Jianzocorp. He is one of the Queen's Young Leaders and campaigns for autism awareness and for a change in policy on gambling regulations.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.