My South African Adventure: 'Is Rugby Racist?'

Cath Everett examines why if you are black in South Africa you play football, and you are if white you play rugby

South Africa must be one of the few countries in the world in which the sport you watch, or play for that matter, is largely dictated by the colour of your skin.

While it's always a bit tricky to trade in stereotypes, as a general rule, the games that people enjoy here appear to be linked to the racial categories assigned to them under the apartheid regime that was disbanded 20 years ago.

If you're black in this sports-mad nation, chances are that you will support, or maybe even play for, a local football team – or soccer as it's known here. This includes Bafana Bafana, the national side.

If you're white, you'll almost certainly be into rugby, and maybe a bit of cricket too – although the latter is also popular among members of the Indian community as well.

People of mixed-race, coloured ethnicity, meanwhile, are likewise generally keen on a bit of rugby, but usually support an international soccer team too, with favourites including Manchester United and Arsenal.

But the government is trying to put a stop to all of this. So, in April this year, it took the controversial step of upping the quota for black and coloured players in certain national sports teams from 50% to 60% in a bid to redress historical imbalances in selection procedures.

These teams, which include the Proteas (cricket) and the Springboks (rugby), have so far mostly failed to even hit the 50% requirement.

Unhappy with the speed of so-called "transformation", the minister of sport Fikile Mbalula has now threatened that failure to fall in line will lead to the withdrawal of central funding from all sports bodies. National teams will also be banned from representing South Africa at international events.

To date, his demands have still to be implemented following meetings with representatives of various sporting groups that led to the process being delayed.

Is rugby racist?

But the real target of the minister's wrath appears to be the country's iconic sport of rugby – a situation that has sparked national debate over how racist the sport actually is and the fairness of measures such as positive discrimination to right historical wrongs.

A key point here is that, since 1995 the Springboks have had 182 white players representing them, compared with a mere 56 black or coloured ones. Even today the team is still only able to field three black players at any one time, out of a squad of 35.

One of the main issues, according to specialist rugby writer Liz McGregor, is that 41% of Springboks come from only 40 private, or former Model C schools, which were reserved for white children under apartheid and are located in demographically white areas.

As a result, if South Africa makes it to the Rugby World Cup next year, it will be lucky to field two black players, McGregor said while speaking on African news channel eNCA's recent Checkpoint documentary, Is South African Rugby Racist?

But civil rights organisation AfriForum, which represents the rights of white Afrikaners, attests that rugby is anything but, and that the government is being racist.

It argues that, while rugby may be a popular sport among white South Africans who make up 4% of the total population, basketball is equally popular among African-Americans who make up 10% of the US population, but dominate their chosen sport.

To make its point, the organisation has just taken the contentious issue of quotas to the International Rugby Board (IRB).

The IRB's regulations prohibit racism in the sport, which includes positive discrimination – something that the South African Rugby Union (Saru) fell foul of during this year's Vodacom Cup tournament, when it announced that participating teams had to field seven players "of colour" in their 22-man squads.

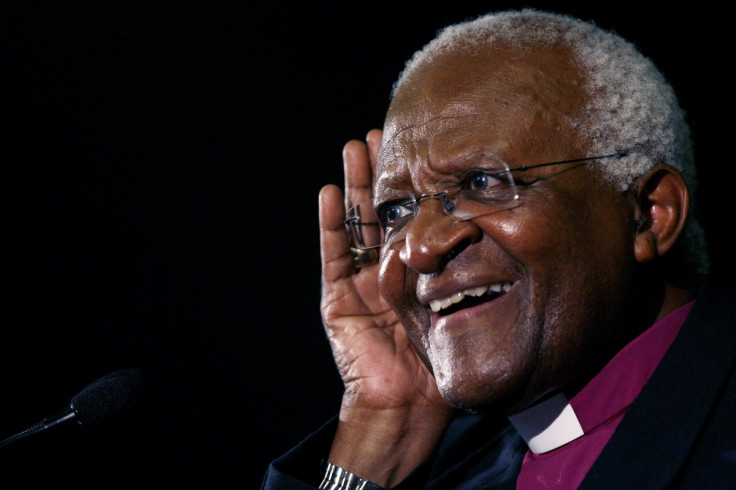

But Anglican Archbishop Emeritus, Desmond Tutu, has now also entered the fray, writing in a letter to The Cape Times newspaper saying that South Africa deserves a team to represent "the full spectrum of the rainbow that defines us".

He criticised South Africa Rugby Union (Saru) for the "tortoise pace" at which transformation was being effected, saying that it was "particularly hurtful" to see the selection of black players as "peripheral squad members never given the chance to settle down and earn their spurs".

Wider forces

Bantwini Matika, coach at Loyiso High School, Port Elizabeth, Eastern Cape, who was also interviewed on eNCA's documentary, was similarly censorious, describing Saru as a "very racist organisation managed by black people".

"It's a classical case of institutional racism," he added. "There are black people in charge, but their systems don't accept black people."

Mervyn Green, Saru's development manager, batted off the criticism, however. "We don't really have a problem in selecting black players just to make up the numbers. We have talent in abundance. We're so blessed in this country with a proper school system that produces top talent year after year."

But it seems that, while Saru and the provincial rugby unions should take at least some responsibility for failing to alter the status quo, there are also wider forces at play.

In defiance of the stereotype, there are "plenty of rugby-mad, majority-black schools in the Eastern Cape", particularly in Port Elizabeth, but they are not getting enough support from the government, according to McGregor.

Limited resources mean that there is simply a lack of infrastructure and technology available in this poor rural province, while high unemployment levels result in poverty and poor nutrition, which in turn adversely affect performance.

On the other hand key white feeder schools have "the same facilities virtually as the Springboks", which include specialist coaches, nutritional guidance and huge institutional and parental support, McGregor said.

But Zola Yeye, a former Springboks' manager, believes that this disadvantageous situation is being made even worse because young black men are kept in special development squads for too long, until they are too old to play or simply injured out. As a result, many of these academies simply become "nurseries and a window dressing exercise".

So, like so many things in South Africa, it would seem that the situation is not as straightforward as it appears at first glance.

And as such, it is unlikely to be solved by simply forcing through blunt instruments such as quotas without effecting much deeper economic and societal change.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.