Mystery surrounding Saturn's icy moon Enceladus, possibly home to alien life, resolved

Origin of tiger stripes of Saturn's moon revealed.

The mystery surrounding Saturn's moon has finally been resolved. A group of researchers has explained the cause behind the moon's "tiger stripes."

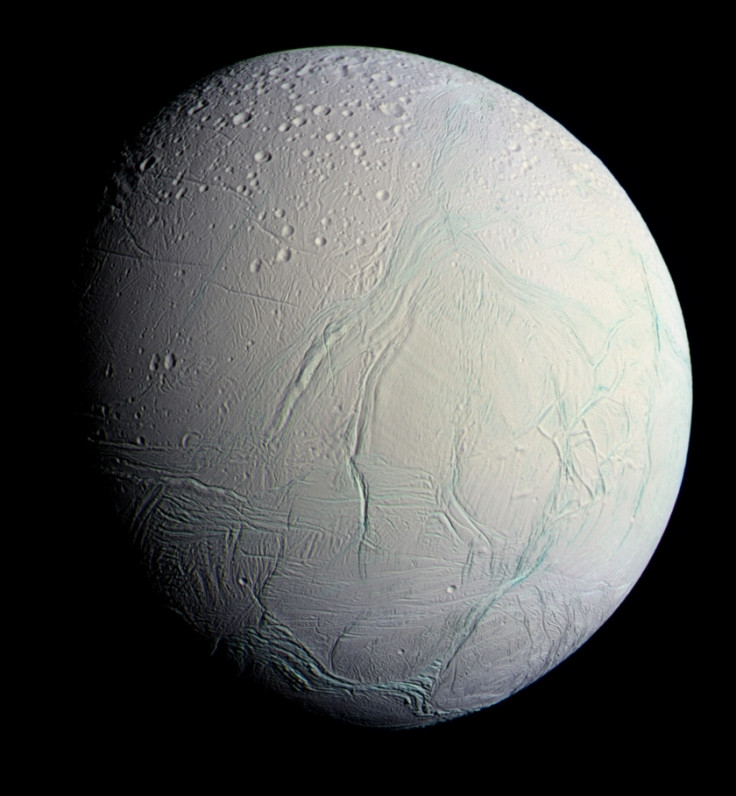

Enceladus, the sixth-largest moon of Saturn was discovered in the 18<sup>th century. The moon has particularly intrigued scientists for years because it is thought to be one of the places where extraterrestrial life might exist, the subsurface moon, and the stripes on its south pole that is unlike anything else in our solar system.

Among so many mysteries, scientists seem to have figured the answer for one, the icy stripes. These four stripes were first observed by NASA's Cassini spacecraft to Saturn. And now researchers have figured the physics behind these linear depressions that open up and emit ocean water creating the fissures.

"They are parallel and evenly spaced, about 130 kilometers long and 35 kilometers apart. What makes them especially interesting is that they are continually erupting with water ice, even as we speak. No other icy planets or moons have anything quite like them," lead author Hemingway explained in a statement as quoted by Space.com.

Strange as it seems, the ocean continues to spill out water, which is often argued as the source of extra-terrestrial life suitable for the evolution. Meanwhile, scientists have many questions regarding the nature and the existence of these stripes. They are curious why the eruptions are located at the South Pole specifically.

The new study has been presented by Hemingway and colleagues Max Rudolph of the University of California, Davis, and Michael Manga of UC Berkeley. They used numerical modelling, which helped them understand the physical forces on the icy shell encasing Enceladus.

They were able to discover what keeps these stripes parallel. It was found out that when the first stripe opened, it remained opened and spewed water. This led to the formation of the other three stripes.

"Our model explains the regular spacing of the cracks," the study's co-author, Max Rudolph, said. He also pointed out that the weight of the icy material that falls back "caused the ice sheet to flex just enough to set off a parallel crack about 35 kilometers away."

The study was published in the science journal Nature Astronomy with the title "Cascading Parallel Fractures on Enceladus."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.