Why the Mars Rover Curiosity is Worth Every Penny [BLOG]

It's been quite a week for displays of how far human achievement can be pushed. While London witnesses the limits of physical accomplishment in the Olympics, another event millions of miles from Stratford has showcased the phenomenal feats that humans can achieve in science and technology.

The Mars Science Laboratory has, over the course of 254 days, covered 560 million kilometres to travel from Earth to Mars. Compare this to the 400,000 kilometres required to get to the moon - it's like comparing a stroll to the local shops with crossing the English Channel.

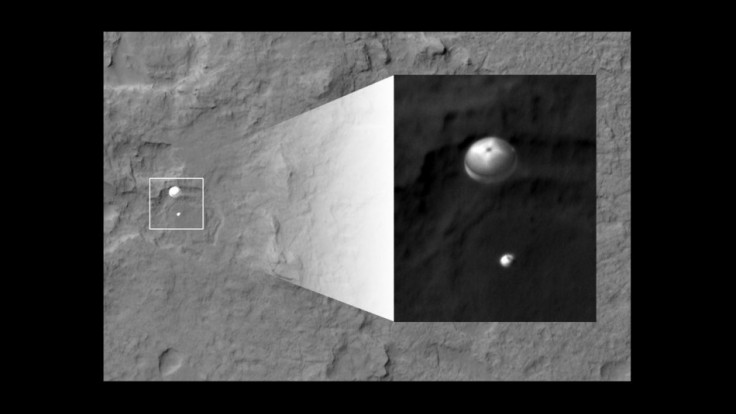

When it reached Mars, the spacecraft plummeted through the tenuous atmosphere of the red planet, before jettisoning its heat-shield and deploying a 16 metre-wide parachute.

Even this wasn't enough to slow it to a safe speed however. Whereas its predecessors Spirit and Opportunity were light enough to survive impact by inflating airbags around them, the Curiosity Rover, which literally weighs a tonne, would have left a brand-new and very expensive crater on the surface of Mars.

Instead, Curiosity was gently lowered to the surface by the skycrane, a hovering craft that dangled the rover beneath it on nylon threads. Having deposited the craft in its landing area, the skycrane flew off to safely crash in the distance. Curiosity will now spend the next few days preparing for a Martian year (two of your Earth years) trundling around the Gale crater, uncovering the history of the planet, zapping rocks with an honest-to-goodness laser gun, and ascertaining the feasibility of a future manned mission.

You probably won't be surprised to learn that depositing a one tonne laser-wielding science robot on another planet isn't cheap. The total cost of the mission is $2.5bn; moreover, it had no guarantee of reaching its target. Far from it - two thirds of missions to the red planet have failed before completing their mission.

Some people are a little wary about investing so much in what may turn out to be a rather pricey planet-to-planet missile. Indeed, space exploration as a whole is often criticised for drawing funds that could be used elsewhere (although I can't help pointing out, as the astrophysicist Neil DeGrasse Tyson has, that more was spent on the 2008 bank bailout than has ever been spent on NASA in its entire 50-year history) and using the money on projects that have no practical benefit.

Nevertheless, here are some reasons I think that venturing out into the black is worth every penny.

Safety in Numbers

The Earth is doomed. That much is certain; how it will happen is the only contentious point. At the very least, 5 billion years from now the sun will swell up and engulf the planet in its death throes (although if we haven't figured out a way off this rock by then, we probably deserve to fry). Before then, it's almost certain that a massive piece of rock will smash into us and make the planet unlivable, putting us and the dinosaurs in the 'close, but no cigar' category. Closer to hand (Republicans and Nigel Lawson can ignore this one), our continued suicidal experiment in altering the atmosphere may see us off for good. Adding in potential plagues, nuclear wars, robot uprisings and zombie apocalypses, our species is far less secure than we think.

So unless you're not all that hot on the continuation of the human race (and you couldn't be blamed for feeling ambivalent after watching a few hours of ITV3), a sensible strategy would be to get the hell off this planet and make a backup. We're currently incapable of even getting anyone out of orbit, and of the few hundred planets we've discovered so far, none of them are exactly cosy.

Nevertheless, we need to learn to crawl before we engage warp drive, and planetary exploration is a vital first step on the long road ahead of us. And if you have any desire at all to do a Kirk and make it with an Orion slave-girl, well, this is the first step to that, too.

Pushing forward

Luddite hankerings for a pre-technological golden age that never existed aside, it's generally agreed that progress is a good thing. Compared to just a hundred years ago, you're far more likely to see your fifth birthday, you have access to a far vaster amount of information, and also, dude, you've got Xbox (all of these assuming you were lucky enough to be born into a first world country of course).

Necessity is the mother of invention, and in the past, the necessity has usually been to find ways to invade and destroy other countries, or prevent others from doing the same. Witness the off-shoots of the last major conflict, World War 2: radar, computers and nuclear power among others.

If there was a way to drive this innovation without the whole pesky death-of-millions thing, then that would be a huge advantage. Luckily, large projects like the Apollo program (and more recently scientific centres like CERN) can provide the nucleus for scientific, engineering and technological progress whilst pursuing a far worthier and less genocidal goal - be that putting a man on the moon, or uncovering the fundamental laws of nature.

Economic studies indicate that every dollar spent on the Apollo program has yielded more than seven dollars back, thanks to the stimulus provided by the R&D performed by the hundreds of scientists, and engineers, who were assembled and given the single goal of safely putting someone on the moon, and getting them back.

Scientific projects like these aren't meaningless vanity campaigns that siphon excess money, and only satisfy the curiosities of a few boffins. They are vital drivers of technological advancement, and we reap far more than we sow when we push ourselves to get them done.

I'll mention in closing that while he was at CERN, Tim Berners-Lee (last seen having a house lifted off him in the Olympic opening ceremony) was trying to solve a problem involving sharing information between computers. He ended up linking between data using hypertext and the internet, and so created the World Wide Web. Had the scientists and engineers working at CERN not been brought together with the entirely separate purpose of particle physics, then it may have been much later that we would have had the ability to waste time at work looking at lolcats.

Our place in the Universe

We've evolved on a planet where, at one time, one can only see a few miles into the distance. This is why standing at the top of a mountain and absorbing the view is such a moving experience; you're struck at once by the enormity of your world, and how insignificant we are in comparison.

The ultimate extension of this experience must lie with the view afforded to astronauts who can look down on our whole planet at once, especially the 12 Apollo astronauts who walked on the moon: the only people to have viewed the Earth from another world. Jim Lovell, the commander of the ill-fated Apollo 13, had this to say.

"We learned a lot about the Moon, but what we really learned about was the Earth. The fact that, just from the distance of the Moon, you can put your thumb up and you can hide the Earth behind your thumb. Everything that you've ever known - your loved ones, your business, the problems of the Earth itself - all behind your thumb."

One of the iconic images of the Apollo missions was the famous 'Earthrise' picture taken in 1968 by William Anders of the Apollo 8 mission. For the first time, people on Earth saw their whole planet as a single, borderless unit, hanging fragile and alone in the void.

Everything humans have ever done is in that few square centimetres - the Pyramids, the works of Shakespeare, Duran Duran, everything

Space exploration does a great deal for helping us appreciate our place in the universe. A quick glance at the papers will confirm that brotherly love is not exactly in plentiful supply around the world, but other than an alien invasion to rally together against, it's hard to see what else, other than gazing further out into the universe, will help us realise what a precious and rare gem our planet is. I'll leave the last word on the subject to Apollo 8 astronaut Frank Borman:

"When you're finally up at the moon looking back on earth, all those differences and nationalistic traits are pretty well going to blend, and you're going to get a concept that maybe this really is one world and why the hell can't we learn to live together like decent people."

Donald Sinclair is a former physics teacher and lecturer who now works as a medical physics researcher / imaging scientist in cancer research at one of London's top hospitals

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.