NASA’s MESSENGER Unlocks Mercury’s Secrets

NASA's MESSENGER spacecraft, the first to achieve orbit around Mercury, has provided scientists with further important information about the planet, by revealing data that showed signs of widespread flood volcanism similar to Earth, provided clearer views of Mercury's surface, provided the first measurements of its elemental composition, and details about charged particles near the planet.

MESSENGER, or the MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging spacecraft, has in the space of six years conducted a total of 15 laps through the inner solar system, and the result of the research are reported in seven papers published in Science magazine Friday.

"MESSENGER's instruments are capturing data that can be obtained only from orbit," says Sean Solomon of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, who participated in the study. "Mercury has many more surprises in store for us as our mission progresses."

The study was launched after scientists debated for years whether Mercury had volcanic deposits on its surface.

The new findings confirm that the planet's north polar Region is surrounded with huge expanse of volcanic plains, which cover more than 6 per cent of the planet's total surface.

According to the reports, the deposits are typical of flood lavas and resemble huge volumes of solidified molten rock similar to those found in the northwest United States.

James Head of Brown University, lead author of one of the papers, said, "If you imagine standing at the base of the Washington Monument, the top of the lavas would be something like 12 Washington Monuments above you."

The research also uncovered vents or openings measuring up to 16 miles (25 kilometres) spread across what appear to be the source of large volumes of very hot lava, which in turn were responsible for carving valleys and creating teardrop-shaped ridges in the underlying terrain.

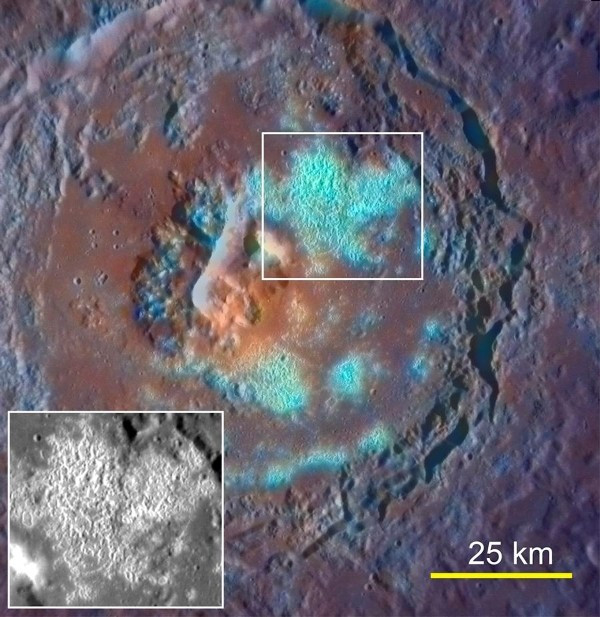

New images also reveal what has been recognised as a new geological process as images of bright areas appear to be small, shallow, irregularly shaped depressions.

The scientists behind the study have named these features "hollows" in an attempt to distinguish them from other types of pits seen on Mercury.

As hollows have been found over a wide range of latitudes and longitudes, scientists now think they could be fairly common across Mercury.

"Analysis of the images and estimates of the rate at which the hollows may be growing led to the conclusion that they could be actively forming today," said David Blewett of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Md., lead author of one of the reports.

Scientists have also made new observations of the chemical composition of Mercury's surface, which is being used to test models of Mercury's formation and continue to study the relationship between the planet's tenuous atmosphere and surface makeup.

Among other findings, the study revealed a higher abundance of potassium than had previously been assumed.

"These measurements indicate Mercury has a chemical composition more similar to those of Venus, Earth, and Mars than expected," says APL's Patrick Peplowski, lead author of one of the papers.

MESSENGER also collected the first global observations of plasma ions, mostly sodium, in Mercury's magnetosphere, which revealed quite weak protection against the solar wind and explained why Mercury's surface environment is hostile with extremes in space weather.

"We were able to observe the formation process of these ions, and it's comparable to the manner by which auroras are generated in the Earth's atmosphere near polar regions," said Thomas Zurbuchen of the University of Michigan, who participated in the study.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.