The North American Indian: Early 20th century photos by Edward Curtis captured a vanishing way of life

Edward Sheriff Curtis dedicated his life to photographing the lives of Native American people. Between 1907 and 1930, he produced 20 volumes of a series called The North American Indian, documenting a way of life that was already beginning to die out.

He began photographing Native Americans in 1895, when he met Princess Angeline, also known as Kickisomlo, the daughter of Chief Sealth of Seattle.

Three years later, the US National Photographic Society selected three of his photos for a major exhibition. Two were of Princess Angeline (The Mussel Gatherer and The Clam Digger) and another, entitled Homeward, won the exhibition's grand prize and a gold medal.

In 1906, banker and philanthropist JP Morgan commissioned Curtis to produce a series on North American Indians.

Curtis was given $75,000 for his work, which was expected to take five years. In fact, Curtis spent more than 20 years creating the series.

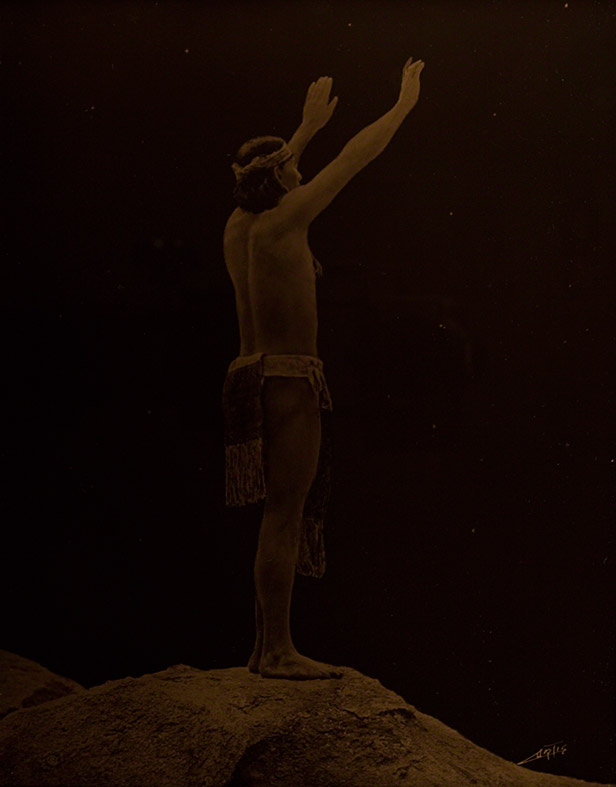

He didn't just take photos – he also made over 10,000 wax cylinder recordings of Indian language and music. He documented tribal customs and history, and wrote detailed descriptions of traditional foods, housing and ceremonies.

In 1912 he made a film called In the Land of the Head Hunters. This was the first feature-length film whose cast was composed entirely of Native North Americans.

He sold the rights to the American Museum of Natural History for $1,500. It had cost him more than $20,000 to film.

While working on his North American Indian series, he was away from home for long periods. His wife Clara eventually filed for divorce. In 1919 she was awarded his photographic studio and all of his original negatives as her part of the settlement. Curtis went to his studio and destroyed all of the glass negatives, rather than have them become his ex-wife's property.

Curtis died of a heart attack in Los Angeles on 19 October, 1952, at the age of 84.

Original printings of The North American Indian fetch high prices at auction, as only 272 copies were made.

While he is generally praised as a gifted photographer, Curtis has been criticised for retouching and staging some images. He often removed any trace of modern-day Western way of life from his photos.

In this photo called In a Piegan Lodge, he removed the clock between the two men seated on the ground. (Mouse-over the image to see both versions.)

He also paid Native Americans to pose wearing historically inaccurate dress and stage simulated ceremonies.

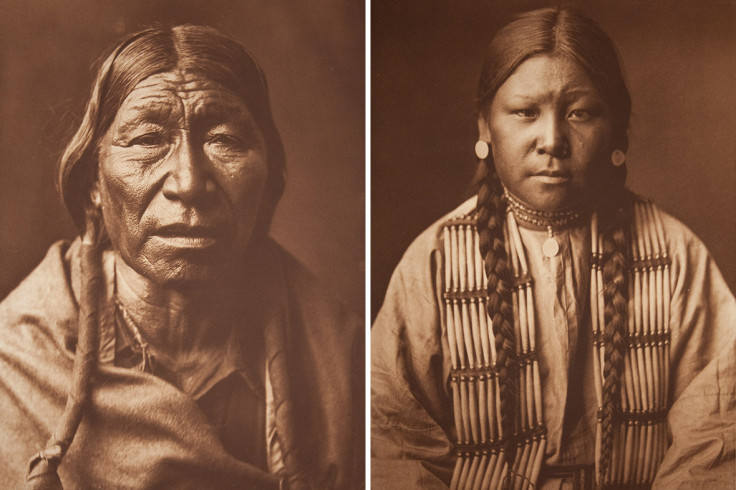

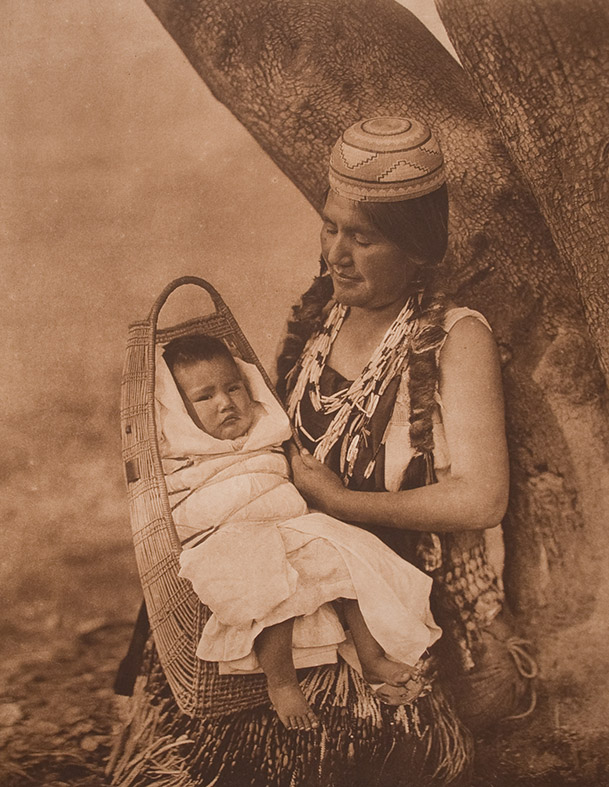

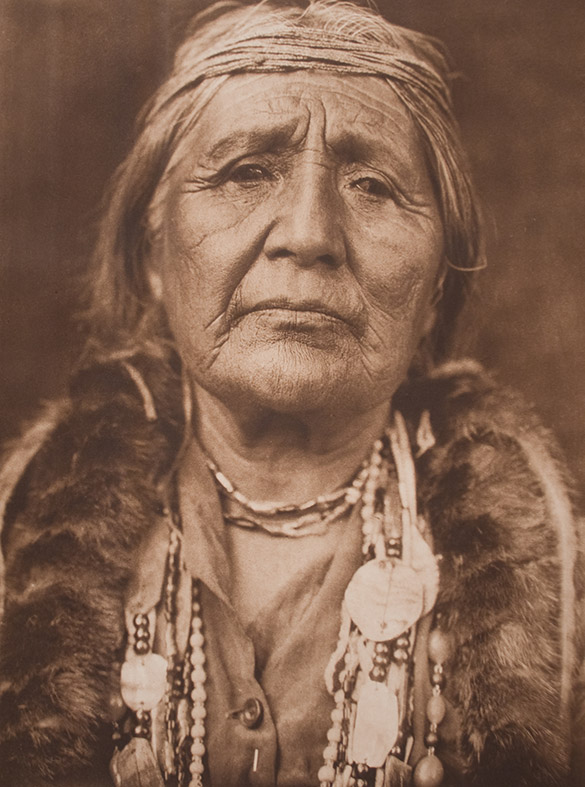

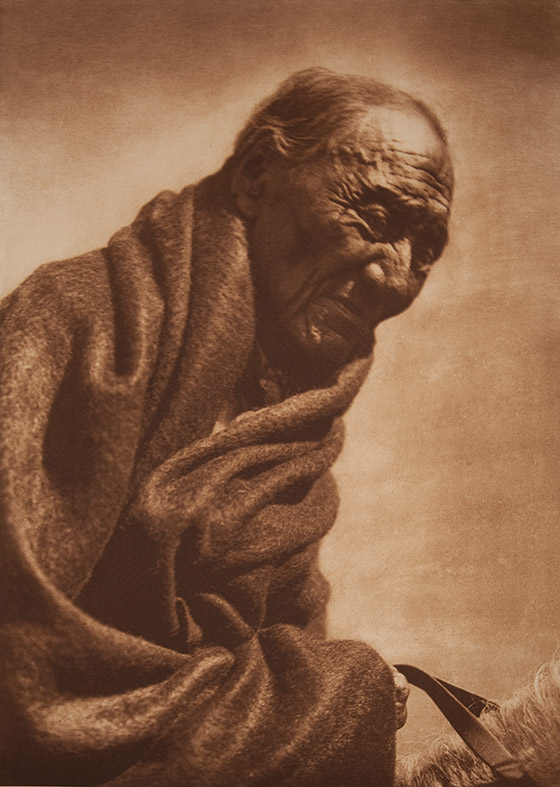

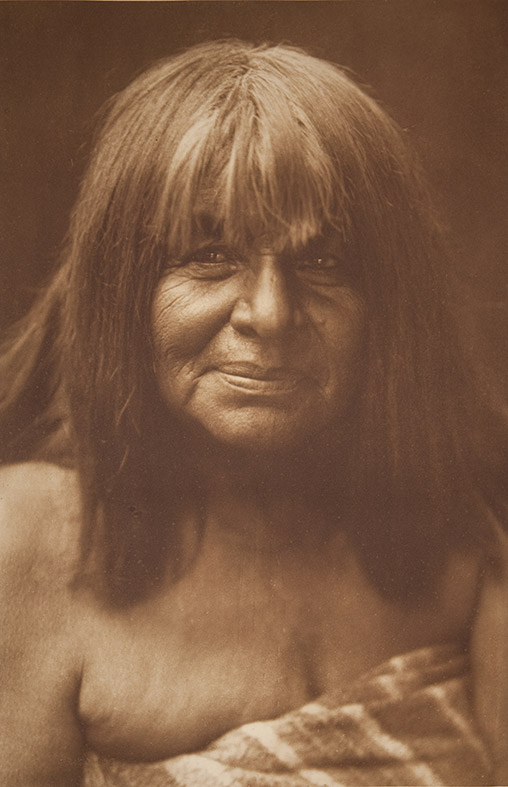

But his photos and descriptions are often the only written history of Native American life in the early part of the 20th century. His biographer Don Gulbrandsen wrote: "The faces stare out at you, images seemingly from an ancient time and from a place far, far away... Yet as you gaze at the faces the humanity becomes apparent, lives filled with dignity but also sadness and loss, representatives of a world that has all but disappeared from our planet."

Laurie Lawlor, author of Shadow Catcher: The Life and Work of Edward S. Curtis, said: "Many Native Americans Curtis photographed called him Shadow Catcher. But the images he captured were far more powerful than mere shadows. The men, women, and children in The North American Indian seem as alive to us today as they did when Curtis took their pictures in the early part of the twentieth century.

"Curtis respected the Indians he encountered and was willing to learn about their culture, religion and way of life. In return the Indians respected and trusted him. When judged by the standards of his time, Curtis was far ahead of his contemporaries in sensitivity, tolerance, and openness to Native American cultures and ways of thinking."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.