North Korea: International journalists arrive for party congress – but are taken to wire factory instead

Foreign journalists visiting North Korea to cover its Seventh Workers' Party Congress, the first congress held since 1980, were denied access to the event. They were taken in buses to the April 25th Cultural Palace, a large congressional hall in central Pyongyang where the event is being held, but were only allowed to stand and report from hundreds of metres away.

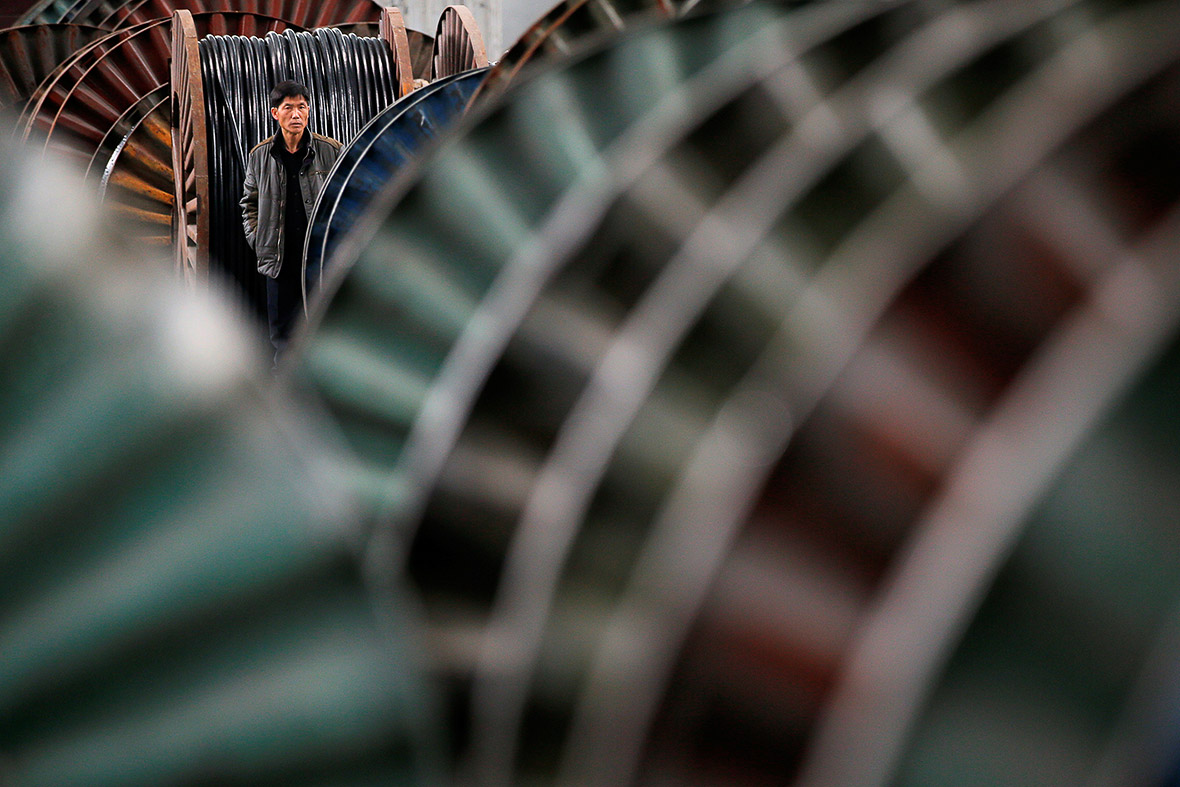

Instead, and somewhat bizarrely, the journalists, who had travelled to North Korea from all over the world to cover the congress, were given a tour of a "model" copper and aluminium wire factory. Officials at the Pyongyang 326 Electric Cable Factory boasted of record production.

For the journalists, the only glimpse of daily life in Pyongyang is from windows of buses, seated next to their North Korean minders keeping a tight watch. Anna Fifield, a correspondent for the Washington Post, said her colleagues in Seoul seem to be more informed about the events of the congress than she is.

"It's North Korea. I'm happy that we are here and able to stand at the front, but at the same time, yeah, it's frustrating not to get any access or any information and then, yeah, this afternoon, to be taken to a wire factory of all things, that has nothing to do with the reason we are here and to be walking around talking to the manager of the factory when we know there's another story going on in town," Fifield said.

The previous day, members of the media were taken to a model farm and had to sit through a two-hour-long gala of music, singing and acrobatics at a "children's palace". Reporters have been offered the chance to visit other locations, including founding president Kim Il-sung's birthplace and a maternity hospital.

It is not yet clear whether foreign journalists will get access to the congress, expected to last between three and five days. Inside the imposing venue, North Korea's 33-year-old leader Kim Jong-un is presumed to be outlining his "Byongjin" policy of simultaneous pursuit of nuclear weapons and economic growth. He is also expected to further consolidate his power.

No one among the overseas press could know for sure, however. The lack of information about the biggest news story in town is hardly a surprise for a country that is notoriously secretive and isolated from the rest of the world. Even state television does not carry live coverage from the congress, and only the presence of a ring of roughly one hundred guards, dressed in identical business suits and holding umbrellas in the rain, gave clues that Kim might be there.

When journalists returned to the press centre at their hotel, cloistered on an island on the Taedong River, four large flat screen TVs had been turned on for the first time. Instead of the congress, the morning's TV programmes included Korean People's Army concerts and old propaganda films.

Still, it is possible to report on some of the economic changes happening in North Korea. The Pyongyang skyline is rising, despite international sanctions imposed in retaliation for North Korea's nuclear weapons programme, and locals can be seen purchasing goods using an unofficial exchange rate. Solar panels also line the balconies of Pyongyang apartment buildings, an indication of people taking power into their own hands amid the country's ongoing energy shortages.

Journalists have been allowed to stop and interview citizens of Pyongyang with almost unrestricted freedom. Some interviewees engage in casual conversation, but in front of television cameras, each thanks Kim Jong-un for his hard work building a thriving socialist nation. "Whenever I come here, I feel the love and affection of our great Marshal Kim Jong-un," said eight-year old Sun Ji-hoon, one of the performers at the children's palace.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.