Oscar Pistorius to be released: Punishment for violence against women rarely fits the crime

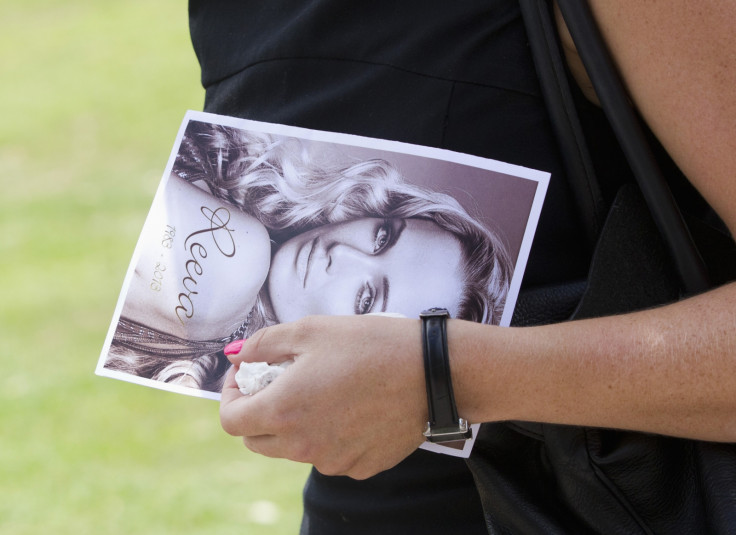

After a trial that lasted six months, Oscar Pistorius was handed a sentence of five years for killing his girlfriend Reeva Steenkamp, with whom he shared a home, under a culpable homicide charge. Eleven months later, he is set to be released to go into house arrest to spend the rest of his sentence at his uncle's house in an affluent Pretoria suburb. It seems the life of one woman is not even worth a year of her killer's.

The release will be within South Africa's sentencing guidelines, which state non-dangerous prisoners should only spend one-sixth of a custodial sentence behind bars before being moved to correctional supervision, depending on good behaviour and rehabilitation prospects. But in a country with one of the highest rates of gender-based violence in the world, the early release of Pistorius sends out a dangerous message in a country where physical and sexual violence against women is an enduring problem.

A woman is killed by an intimate partner in the country every eight hours in South Africa. Although the country's annual crime figures, released in September, saw the number of sexual offences drop by just over 5% to 53,617 between 2014-2015, most researchers agree the figure reflects only a fraction of those that actually occur – largely due to underreporting. Pistorius' release might be legitimate in line with the country's culpable homicide charge – equivalent to the UK law of manslaughter – but it does not make it right.

Steenkamp's parents have maintained Pistorius killed their daughter on purpose and they have consistently opposed parole. In August, when Steenkamp would have turned 32, her mother told a South African tabloid: "For our beautiful daughter – for anyone's life – it's definitely not long enough. She was robbed of her future, her career, her chance to get married and have a baby."

Intimate partner violence is a global problem. Horrifying statistics tell the story time and time again: more than a third of women worldwide have experienced either physical and/or sexual partner violence at the hands of a partner or non-partner, and of all women killed in 2012, almost half were killed by partners or family members. The treatment of women as second-class citizens is a pandemic.

The problem was also one Steenkamp was all too aware of. On 13 February 2013, the day before she was killed, she announced her support for a "Black Friday" demonstration in protest of the number of South African women raped and murdered. A friend of Steenkamp who knew her through her burgeoning law career, Kelly Smith, said the pair had plans to start a firm to help abused women.

The lack of accountability equally harrowing, and itself a problem that fuels violence against women. Perpetrators have a sense of impunity which is fairly substantiated – in 2009, South Africa's intimate femicide rate was more than double the rate in the US, but in more than 20% of murders, no perpetrator was identified. Steenkamp was already using her rising profile to raise awareness of violence against women, as the voice of an immeasurable number of women killed who remain nameless. So many perpetrators are never brought to justice, leaving the families, friends and children left to grieve with no closure.

"Violence against women should be treated as seriously as any other crime," says Sandra Horley, chief executive of national domestic violence charity Refuge. "An assault is an assault – whether it happens in broad daylight or behind closed doors. Sadly, we know that often the sentences given out to men who abuse women rarely fit their crimes – and that many perpetrators still go unpunished.

"Correct sentencing not only means that men are punished appropriately, but that other abusive men receive a strong warning that a similar fate awaits them should they continue to offend. Poor sentencing reflects the need for further training: it is essential that all professionals involved in the criminal justice system properly understand the complex risks and dynamics of domestic violence and other forms of violence against women."

"The courts need to send out a strong message to abusive men and to the public: that violence against women is never acceptable and there will be serious consequences for anyone found guilty of these crimes," Horley adds.

Aggressive masculinity is the root cause of violence against women. Pistorius' trial revealed snapshots of the athlete's volatile side, as well as a penchant for guns, fast cars and women. He was "jealous and insecure" and, according to Steenkamp herself in a text message she sent to Pistorius, he could be threatening. "I am scared of you sometimes and how you snap at me," she wrote.

The problem is part of a thriving macho culture which prevents women from reaching the higher echelons of their careers, keeps the pay gap open and sees pre-teen girls married off to men five times their senior. It is a culture which prevents 62 million girls from receiving the education they need to thrive, fuels the continuation of female genital mutilation and, fundamentally, means all women of any age, ethnicity, race, sexual identity and class are at risk of violence, and death.

"Thirty-eight per cent of all women who have been murdered have been murdered by their intimate partners. Violence against women and girls is a human rights crisis that states are obliged to take action to end," says Bethan Cansfield, policy manager at Womankind Worldwide. "But all too often we see low levels of convictions, short sentences given to perpetrators and survivor-blaming from state officials – all of which send the message that these crimes are not taken seriously."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.