Over 300 child soldiers lay down their weapons after being released by armed groups in South Sudan

Over 19,000 children are thought to have been recruited, often by force, by armed groups on all sides of South Sudan's brutal civil war.

More than 300 child soldiers were released by armed groups in South Sudan on Wednesday (8 February), the second-largest such release since civil war began five years ago. Over 19,000 children are thought to have been recruited, often by force, by armed groups on all sides of South Sudan's brutal civil war.

The "laying down of the weapons" ceremony for 87 girls and 224 boys was the first step in a process that should see at least 700 child soldiers freed in the coming weeks, the United Nations said.

Some 215 children were released by the South Sudan National Liberation Movement (SSNLM), which in 2016 signed a peace agreement with the Government and is now integrating its ranks into the national army.

Additionally, 96 children were released from the ranks of the Sudan People's Liberation Army-In Opposition (SPLA-IO), the biggest rebel group, which is led by former vice president Riek Machar.

The Associated Press interviewed a 17-year-old boy who had been abducted and forced to fight. He gave only his first name, Christopher. "They told me to kill my mother," he said, his voice barely audible. After being seized from his home by opposition soldiers at the age of 10 during a period of localised fighting, he said his mother came into the bush to plead with his commanders to set him free.

"When she came they told me to shoot her or I'd be killed instead," the boy said. "I had no option, I just asked God to forgive me." But he had never shot a gun, and when he pulled the trigger it jammed. His mother escaped. Now freed, Christopher said his family has forgiven him.

Reuters spoke to 14-year-old girl named Bakhita, who was snatched by armed rebels from her family farm two years ago. "I was thinking of my family every day. Sometimes I cried but I couldn't escape, the soldiers were everywhere in the bushes," Bakhita told Reuters. "There's no house. We sleep in a tent. Sometimes at night, some soldiers come to my place and want to rape me by force. If I resist, they will beat me and make me cook for a week as a punishment for refusing to sleep with them," she said, beginning to cry.

An upsurge of fighting in the region in July 2016 stalled the progress that had been made in securing the release of children associated with the forces, but this release is a positive step forward.

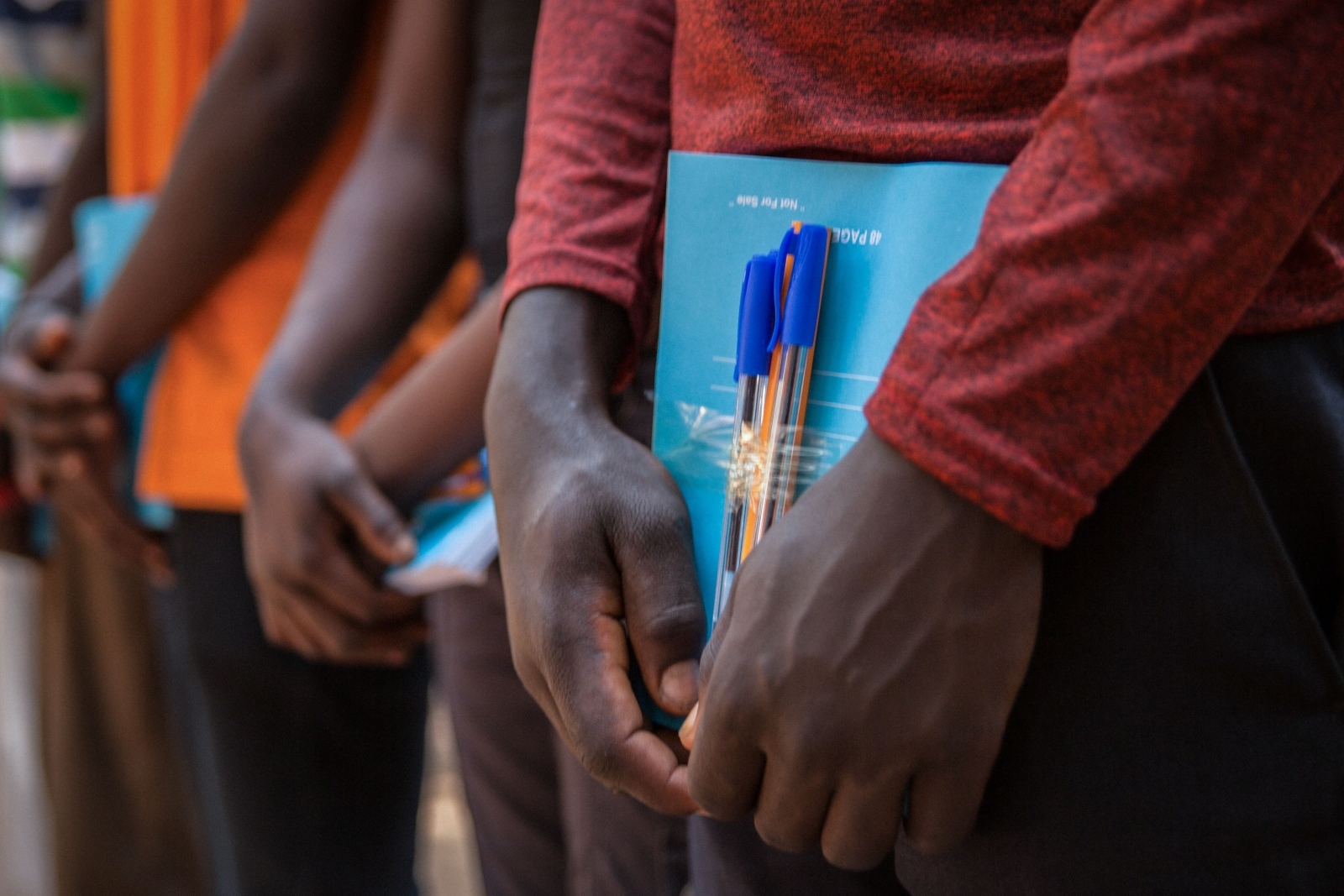

During the release ceremony, the children were formally disarmed and provided with civilian clothes. Medical screenings will be carried out, and children will receive counselling and psychosocial support as part of the reintegration programme, which is implemented by Unicef and partners.

Those with relatives in the area will be reunited with their families, while others will be placed in interim care centres until their families can be traced. When children return home, their families will be provided with three months' worth of food assistance to support their initial reintegration. The children will then be provided with vocational training aimed at improving household income and food security. Being able to support themselves economically can be a key factor in children becoming associated with armed groups.

"This is a crucial step in achieving our ultimate goal of having all of the thousands of children still in the ranks of armed groups reunited with their families," said Mahimbo Mdoe, Unicef Representative in South Sudan. "It is the largest release of children in nearly three years and it is vital that negotiations continue so there are many more days like this."

"Not all children are forcibly recruited. Many joined armed groups because they feel they had no other option," said Mdoe. "Our priority for this group – and for children across South Sudan – is to provide the support they need so they are able to see a more promising future."

Putting down weapons and rejoining normal life is just the "beginning of the journey," said the head of the UN mission in South Sudan, David Shearer.

In addition to services related to livelihoods, Unicef and partners will ensure the released children have access to age-specific education services in schools and accelerated learning centres.

Although aid workers were optimistic, they worried that renewed violence could force the children back into armed groups. A new round of peace talks began this week in neighbouring Ethiopia, mediated by a regional bloc. "If peace isn't sustained and people are forced to the bush, we'll lose these children," said Anne Hadjixros, a child protection officer with Unicef.

Human rights groups say child recruitment continues, even as South Sudan's government says it has committed to ending the practice. "The continued recruitment and use of children by the military and opposing armed groups points to the utter impunity that reigns in South Sudan, and the terrible cost of this war on children," Mausi Segun, Africa director at Human Rights Watch, said in a new report this week.

Speaking at the release ceremony, South Sudan's First Vice President Taban Deng Gai called the release of child soldiers a sign of peace. He also warned other countries, particularly the United States, against criticism from those in "glass houses". Some in the East African nation have responded angrily after the US imposed an arms embargo last week. The vice president said the US had had to learn from its mistakes and South Sudan would, too.

Oil-rich South Sudan became the world's youngest nation when it won independence from Sudan in 2011. Civil war broke out two years later, eventually forcing a third of the 12-million strong population to flee their homes.

Unicef will continue to work with all parties to the conflict, as well as UNMISS, to secure the future release and reintegration of all children associated with armed groups through a meticulous process of negotiation, verification and registration. Adequate funding for Unicef release programme is essential. The UN Children's Fund requires £32 million ($45m) in 2018 to support release, demobilisation and reintegration efforts across the country.