Paradox of the 'iceberg armadas' in the depths of the last Ice Age resolved

Understanding how ice sheets behaved during the Ice Age can refine our predictions of how fast Antarctica will melt with climate change.

Huge numbers of icebergs broke off from the ice sheet that covered much of North America in the last Ice Age – but only during the coldest periods. Scientists now think they have solved the problem of why the ice sheet broke up so quickly when temperatures were low.

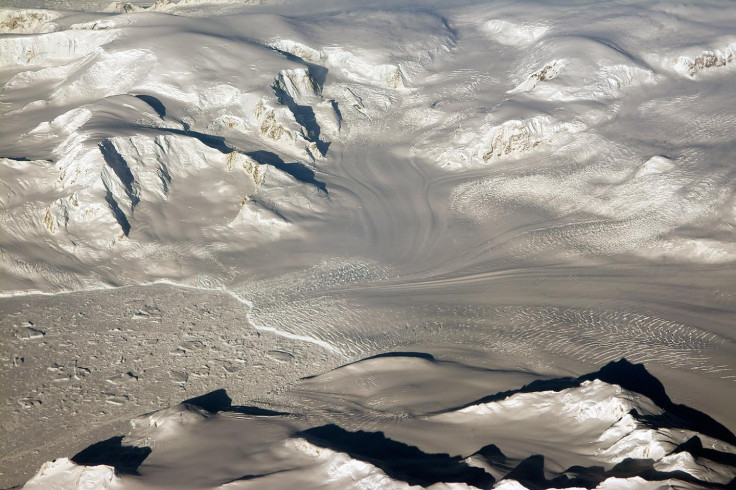

The Laurentide Ice Sheet covered a vast expanse of present-day Canada and the northern US during the last Ice Age. Icebergs would occasionally break off in huge numbers and spread into the Hudson Strait and the North Atlantic Ocean. This mass-calving of icebergs is known as a Heinrich event.

A paper in the journal Nature proposes that Heinrich events at the fringes of the Laurentide sheet happened when ice spread out along the land, which started to deform under their weight. This pushed the hard crust down on the semi-molten mantle, lowering the level of the land, bringing the base of the ice sheet below sea level. Exposure to the warm water then triggered the disintegration of the ice sheet and the release of the 'iceberg armada', the authors say.

"We've shown that we don't really need atmospheric warming to trigger large-scale disintegration events if the ocean warms up and starts tickling the edges of the ice sheets," said study author Jeremy Bassis of the University of Michigan in a statement.

"It is possible that modern-day glaciers, not just the parts that are floating but the parts that are just touching the ocean, are more sensitive to ocean warming than we previously thought."

Predicting sea level rise

In the last Ice Age, which ended more than 10,000 years ago, this sudden release of icebergs from the Laurentide sheet led to a sea level rise of more than 6 feet over a period of a century. Although Heinrich events only happen during glacial periods, there are some ways in which modern ice sheets show behaviour analogous to these events.

The models based on the Heinrich events of the Laurentide sheet fit well with the behaviour of Greenland's ice sheet today, Bassis said. The West Antarctic Ice Sheet also has a comparable structure to the Laurentide sheet, particularly the fast-retreating Pine Island and Thwaite glaciers.

"We're seeing ocean warming in that region and we're seeing these regions start to change. In that area, they're seeing ocean temperature changes of about 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit," Bassis said.

"That's pretty similar magnitude as we believe occurred in the Laurentide events, and what we saw in our simulations is that just a small amount of ocean warming can destabilise a region if it's in the right configuration, and even in the absence of atmospheric warming."

Last year another paper in the journal Nature revised up the expected amount of sea level rise from millimetres to more than a metre.

The comparison between the Ice Age Laurentide sheet and present-day Antarctica is a useful line of research for guiding predictions of the effects of climate change, Jennifer Stanford, a researcher at Swansea University who studies Heinrich events, told IBTimes UK.

"In terms of thinking about rates we could start to see Antarctica de-glaciate, it's important to look at past analogies to see whether we could draw a link to what might happen," Stanford said.

"This analogy is quite good. In Antarctica we have marine-based ice shelves: you have the ice shelves that extend out like a tongue of ice onto sea, and then you have your land-based ice.

"That's exactly what you had in Laurentide extending out down Hudson Strait, and behind that you had land-based ice. The question is, when you take that ice shelf away, how quickly does the land-based ice disintegrate behind it?"

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.