Paris attacks: George Osborne risks reputation with spending cuts to army and police

"He found that his Chancellor was wanting some swingeing cuts in welfare state expenditure, more than was feasible politically. [He] was challenging the whole ethos of post-war conservatism."

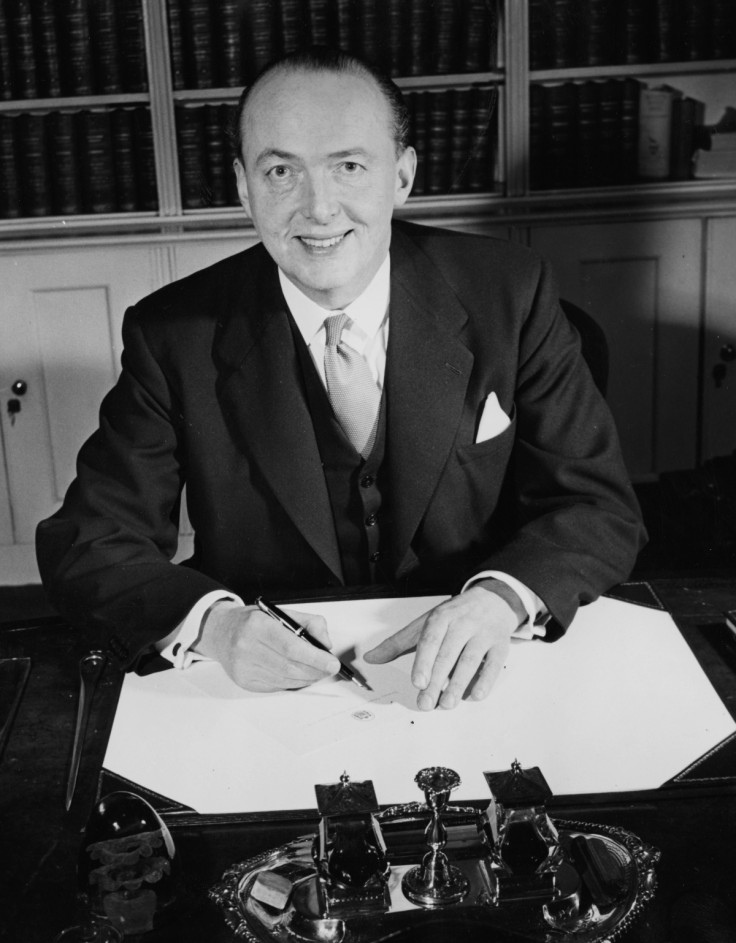

That quotation comes from Edmund Dell's magisterial book on British Chancellors of the Exchequer. It refers not to Prime Minister David Cameron and Chancellor George Osborne, but to Prime Minister Harold Macmillan and Chancellor Peter Thorneycroft in late 1957.

Macmillan was vehemently against the public spending cuts being proposed by Thorneycroft, who resigned over the issue, along with two fellow Treasury Ministers, in January 1958. Macmillan brushed off their resignations with a famous phrase describing them as "a little local difficulty", and then went ahead, in unflappable style, with a planned Commonwealth tour.

It is the present position of Chancellor Osborne that reminds me of this episode. There are parallels, but there are also crucial differences. Like Thorneycroft before him, Osborne has so far been insisting on cuts to the welfare budget which are looking politically unfeasible.

Having won this year's general election, the Conservative government in general and its Chancellor in particular tried to convince themselves and the public that they had a mandate for swingeing cuts in tax credits. These alleviate the financial burdens of people on low pay, and are also intended to encourage higher employment.

In his July budget speech, Osborne argued that other changes, principally an ambitious increase in the minimum wage, would compensate most of the losers. Since then there has been an avalanche of impressive analysis from highly respected think tanks that this would be far from the case. Moreover, the message has got through to Conservative members of Parliament, who are in open revolt and in increasing numbers.

The arrogance of Osborne's cynical approach to this revolt was well illustrated when he told one Tory MP not to worry because he had a very safe seat in his particular constituency. He was swiftly told that was not the point - the MP actually cared for the many constituents he represented who would be badly hit if Osborne went ahead.

Now, it so happens that Harold Macmillan is one of David Cameron's political heroes. It also happens that Cameron has from time to time insisted that, like Macmillan, he believes in what is known as One Nation Conservatism - that is, the ethos of that post-war conservatism referred to by Edmund Dell in the above account but most certainly eroded by the sharp move to the right under Margaret Thatcher.

However, whereas Macmillan did not approve of unnecessary austerity measures, and was not especially close to Thorneycroft, on the evidence so far Cameron and Osborne are, as the saying goes, 'as thick as thieves'.

Thus Cameron has so far gone along with Osborne's controversial aim of swingeing cuts in public spending. These are part of a two fold aim: one is to achieve, for doctrinal reasons (no serious economist thinks this is necessary) not only a balanced budget but a budget that is in annual surplus on both current and capital account (capital spending, in both public and private sectors, obviously needs long term finance. Few people pay off their mortgage in one year).

The second aim is to make room for tax cuts aimed principally at the better off. This very aim contradicts the argument that the cuts are somehow "necessary".

Like his hero Macmillan, Cameron has a reputation for being unflappable. He is certainly a very smooth operator on public occasions. But Macmillan also had a reputation for ruthlessness with colleagues who proved unpopular. Until now Osborne has given the impression that he thinks he can walk on water.

But the terrible events in Paris have, by chance, highlighted another problem with his cuts. Until now he has also been planning drastic cuts in budgets for the armed forces and the police. Cameron has, not surprisingly, announced that as a result of Paris attacks he is going to increase spending on the key intelligence departments MI5, MI6 and GCHQ.

It was Macmillan who famously said that what he most feared was "the opposition of events." The newly re-elected Conservatives have been congratulating themselves on the weakness of the official opposition. Their austerity programme is now up against events. And Osborne's reputation hangs in the balance.

William Keegan is a journalist, academic, and the senior economics commentator at The Observer. He has published his latest work – Mr Osborne's Economic Experiment - Austerity 1945-51 and 2010 (published by Searching Finance).

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.