Pay Power: How the Minimum Wage Movement Went Global

Workers of the world are eyeing a pay rise. From cleaners in Salford, to waitresses in Seattle –more and more pressure is being put on legislators to hike and introduce statutory minimum wages. Now, as the Great Recession is confined to the history books and economies build momentum, the cry for fairer wages grows stronger.

Predictably, the social democracies of Western Europe are facing rate rises. Angela Merkel made history in April when she approved Germany's first minimum wage of €8.50 per hour (£6.93, $11.66).

But the move may not have ever happened if Merkel's Christian Democratic Union (CDU) had its way. The party originally resisted a statutory flaw, instead supporting the tried and tested method of wage rates set by the outcomes of collective barraging agreements between employers and workers. However, the pursuit of power changes the CDU's position.

The canny Merkel proposed a statutory minimum wage in all but name in 2011. Later, when her party sealed a deal with the left-wing Social Democratic Party (SDP) to secure Merkel a third term in late 2013, the "Grand Coalition" agreement wiped the CDU's euphemisms on the wage question away – there would be a statutory hourly rate of €8.50 by 2015.

The phenomenon of more and more low-paid work in typically un-unionised industries was the driving force behind Germany's historic move. The same trend seems to be behind Ed Miliband's promise to "significantly increase" the UK's current national minimum wage of £6.31 an hour.

In fact, Miliband's "Cost of Living Crisis" campaign has shades of "Poor Despite Having a Job" – the convincing slogan the chairman of the German Federation of Trade Unions (DGB) deployed while campaigning for a statutory rate.

Miliband's election pledge comes after the Conservative and Liberal Democrat parties called for an increase in the rate. Even the Conservative Chancellor George Osborne argued that employers could afford to pay-out more to their low-paid employees.

Osborne's comments were significant. It meant that the country's national minimum wage, introduced under a New Labour government in 1998, was endowed with "sacred cow status". Only two other British institutions enjoy such bipartisan support – those are the Armed Services and the National Health Service (NHS).

But the Minimum Wage Movement's momentum slowed recently when it suffered a blow in Switzerland. The rich, egalitarian Western European state said no to a statutory minimum wage of CHF22 (£14.66) an hour.

In a country-wide vote, a vast majority (76.3%) of voters rejected the proposal amid fears that the measure would cause job losses. Like Germany, wage rates are set by collective bargaining agreements. The issue is the same – workers who don't have strong union representation tend to get lower wages.

But it seems the proposed rate, which would have meant the Swiss would enjoy the highest national minimum wage in the world, was just too high for voters to stomach – in spite of the high costs of living associated with the country's main cities.

Maybe the comrades at the Swiss Federation of Trade Unions, which was one of the driving forces behind the proposal, should have aimed lower.

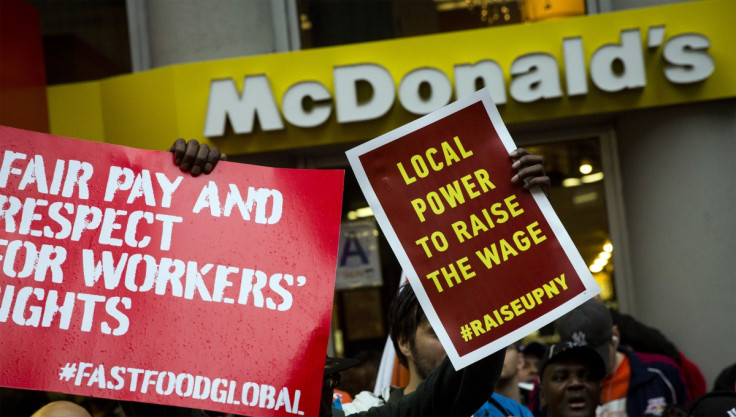

The same cannot be said of trade unions and workers in the United States who are calling on legislators to increase the country's measly Federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour to $10.10. But the Democrat Party's bill to increase the rate was blocked by Republicans in Congress. Campaigners have now focused their attention individual state rates, coinciding with protestors hoping to increase the pay of fast food workers across the world's largest economy.

It seems the fight for fair wages has gone global. The Minimum Wage Movement could be easily rejected as misguided utopianism, but the Swiss poll result shows that the workers understand that if employers have to pay too higher price, jobs will be lost.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.