Penguin poo in Antarctica reveals 6,700-year history of deadly volcanic eruptions

The gentoo penguins of Ardley Island have shown remarkable resilience for thousands of years.

Ancient penguin poo in lake sediments at Ardley Island on the Antarctic Peninsula suggests that the gentoo penguin population was repeatedly decimated by huge eruptions from the Deception Island volcano.

The gentoo penguin colony at Ardley Island, which lies close to the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, is the largest in Antarctica. Today there are some 5,000, to 6,000 breeding pairs of penguins living there. But they have had a turbulent history, recovering from several enormous eruptions that pushed the population to the brink of extinction.

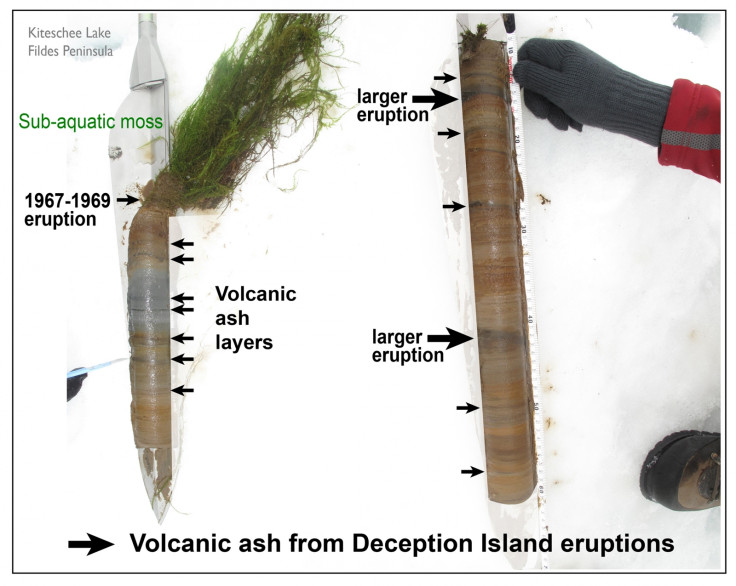

The lake sediments at Ardley Island have trapped a record of the poo of the birds that lived on the island for the past 6,700 years. The climate records from lake sediments at the island go as far back as 8,500 years. The sediments also trapped the ash that erupted from neighbouring Deception Island throughout that period. The findings are published in a paper in the journal Nature Communications.

The eruptions are recorded as dark bands in the lake sediment cores, with the larger bands corresponding to more ash coming from larger eruptions. Thicker sections with biological markers showing the presence of penguin poo, or guano, suggests larger populations of the birds.

"What we see after the three biggest eruptions is an almost immediate decline in guano in the record," study author Stephen Roberts of the UK's Natural Environmental Research Council told IBTimes UK. "We see a very rapid decline in guano followed by a very slow recovery."

It would be centuries – up to 400 years – before the gentoo populations would recover from the largest eruptions. The falling ash from Deception Island would have covered the ground and made it almost impossible for the penguins to live, breed or nest there.

As a result, the vast majority of the penguin populations died after these events. There is a possibility that some clung on at the island, or else swam to a nearby land mass to survive until the island had begun to recover.

But even the worst that Deception Island could throw at the gentoos didn't destroy their populations entirely, revealing the species' remarkable resistance to repeated natural disasters.

"After the largest eruption, about 5,300 years ago, we see some evidence that the penguins struggled through for quite a while, but in relatively low numbers," Roberts said.

"On a broad scale over a several thousand years they do seem to bounce back. We've seen that they can recover – it might take a long time but they do get there each time. And they still live on the island today. They are pretty resilient."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.