Photos: Isis destroyed priceless Mosul museum artefacts, but preserved palace of Assyrian king

Inside Mosul's antiquities museum, which once housed priceless Mesopotamian artefacts dating back thousands of years.

Mosul's antiquities museum – built in the 1970s and the second largest in Iraq – once housed priceless Mesopotamian artefacts dating back thousands of years and a collection of rare Islamic and pre Islamic texts. Now, after two-and-a-half years under Isis control, piles of rubble fill the exhibition halls. Dozens of Assyrian, Akkadian, Babylonian, Persian and Roman artefacts that the ransacked museum held have all been stolen or damaged.

"What they didn't loot they destroyed," said Lieutenant Colonel Abdel Amir al-Mohammedawi, of Iraq's elite Rapid Response units, who recaptured the museum building. "Some were smuggled out of Iraq," Mohammedawi told Reuters.

Some of the jihadists filmed themselves smashing some of the building's contents including priceless statues with sledgehammers and power tools in 2015, as part of their campaign to erase any cultural history that contravenes their extreme interpretation of Sunni Islam.

The sacking of the Mosul museum was just a single act in nearly three years of systematic destruction of Iraq's cultural heritage at the hands of Isis. The militants levelled ancient palaces, temples and churches throughout Nineveh province and beyond, often releasing videos boasting of their acts. Isis has even demolished some mosques, saying they were used to venerate saints, which Isis considers a form of polytheism.

Now, the large stone wing of a statue of lamassu – an Assyrian winged bull deity – lies on the dusty floor along with smashed cuneiform tablets and other broken remnants of the past. A block engraved with Arabic Islamic calligraphy lies close by, and some Islamic manuscripts have been left undamaged. But almost everything else has gone.

"These are the remains of a lamassu and the lions of Nimrud," Layla Salih, an Iraqi archaeologist and former curator of the Mosul museum told AP. "They were priceless," she said, "they were in perfect condition."

Adjoining rooms on the two main floors are largely empty apart from a set of carved wooden coffins and doors left untouched. There are also smaller piles of rubble from what appear to be additional destroyed artefacts, but the stones are crushed beyond recognition.

A handful of history books remain in the main entryway of the museum beside a bag of placards from old exhibits. They describe flint objects found in Nineveh dating back to about 4,000 BC, copper oil lamps discovered in Ur dating back to 2,600 BC and Sumerian statues dating back to 2,050 BC.

The outside of the building, which features Roman-style columns, is blackened from shell or rocket blasts and peppered with bullet holes. A Chaldean Catholic church next to it has also been mostly gutted, its altar cracked down the middle.

"Daesh came to Iraq to destroy our heritage because they don't have their own," said Federal Police Corporal Abbas Muhammad, who was one of the first to enter the building after it was recaptured.

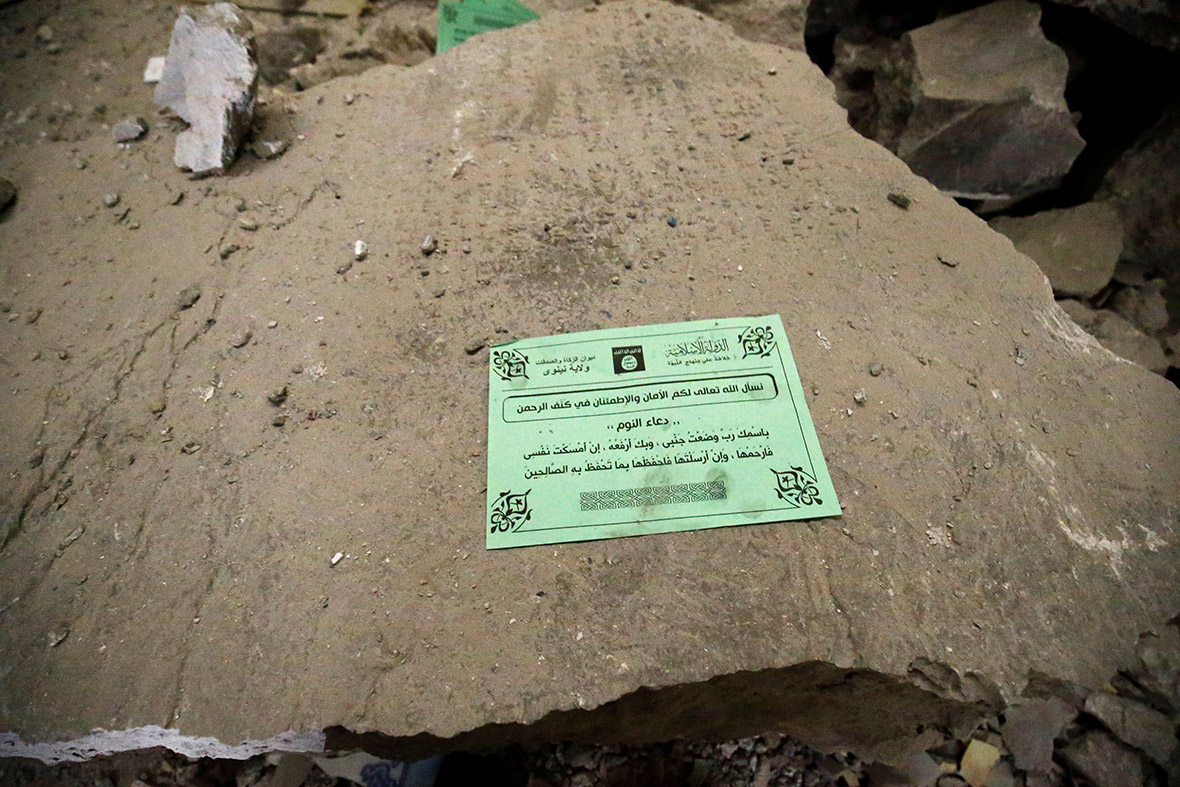

However, a recent discovery elsewhere in Mosul suggests that Isis may have helped to excavate and preserve the palace of an ancient Assyrian king who ruled some 2,700 years ago. The extremists blew up the ancient Mosque of Jonah in 2014 after taking control of the city. They started digging tunnels into the side of the hill under the shrine. The careful way the tunnels were dug show the militants wanted to keep the treasures intact so that they could sell them, said archaeologist Musab Mohammed Jassim, from the Nineveh Antiquities and Heritage Department

"They used simple tools and chisels to dig the tunnels, in order not to damage the artefacts," he said, standing near the tunnel network which leads from the mosque ruins above ground to the much older subterranean palace. The digging "was carried out according to a plan and a knowledge of the palace," he added.

Ancient inscriptions and winged bulls and lions were found deep in the tunnels, thought to be part of the palace of King Esarhaddon, who ruled the Neo-Assyrian empire in the 7th century BC. Esarhaddon was the son of Sennacherib whose military campaigns against Babylon and the kingdom of Judah are in the Bible.

The efforts to avoid damaging some antiquities contrast with the destruction of ancient sites across the self-declared caliphate in Syria and Iraq, from the desert city of Palmyra to the Assyrian capital of Nimrud, south of Mosul. The United States has said the looting and smuggling of artefacts has been a significant source of income for the militants. In July 2015, US authorities handed Iraq a hoard of antiquities it said it had seized from Islamic State in Syria.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.