Technique to Develop Clot to Stem Bleeding Developed

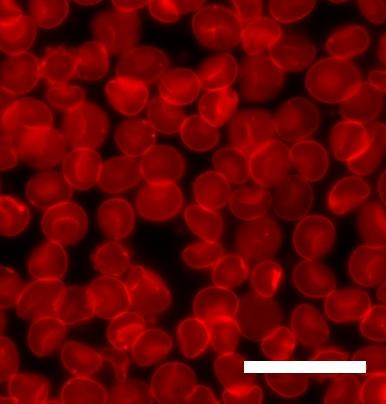

An international team of scientists has come up with a new treatment for emergency internal bleeding. They have developed nanoparticles that make blood platelets rapidly create healthy clots, thereby causing to slow or halt internal bleeding until the victim reaches a hospital and receives blood transfusions and surgery. They claim the new discovery will save many lives across the world.

"We knew an injection of these nanoparticles stopped bleeding faster, but now we know the bleeding is stopped in time to increase survival following trauma," said Erin Lavik, a professor of biomedical engineering at Case Western Reserve University.

Natural platelets, activated by injury, emit chemicals that bind natural platelets, but take a lot of time to stop bleeding. Researchers have developed nanoparticles that make the blood platelets rapidly create healthy clots.

"We began focusing on synthetic platelets after learning the military has no equivalent of a tourniquet, pressure dressing or other easily transportable technology to slow bleeding from internal injuries," said Lavik.

The platelet-like nanoparticles, already approved by the Food & Drug Administration for use in humans, are made of biodegradable polymers used in devices.

To know the effectiveness of nanoparticles, researchers conducted a test on lethal liver injury models in lab rats.

One group of mice received platelets like nanoparticles while the other group was treated with saline alone.

The study found that the survival rate of the mice injected with the nanoparticles was 80 percent. For control groups treated with saline alone the survival rate fell to 47 percent. Mice treated with the platelet-like nanoparticles exhibited the least blood loss.

Researchers also found that the hybrid clots, created by the nanoparticles, were as firm as natural clots. Tests have shown that these synthetic platelets can cut bleeding by as much as half and that, a week later, the rats showed no ill-effects from the materials, according to Eurekalert.

"We are continuing to test the platelets with other models of injury, working toward the best design and dosage for human use," said Lavik.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.