Plummeting vaccination rates mean measles could kill more than Ebola in affected countries

Disruptions to vaccination programmes as a result of Ebola could lead to an outbreak of measles that kills more than the virus itself. Major disruptions in the health care systems of affected West African countries has led to a significant drop in vaccinations for childhood diseases, including measles, diphtheria, and tuberculosis.

Researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health have found that for every month of interruption in the health care system, an additional 20,000 children become susceptible to measles.

Publishing their findings in the journal Science, they said measles epidemics often follow humanitarian crises. "Measles has been seen associated with acute crises, like the Ethiopian famine in 2000, and long term unrest, like a large outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo between 2010 and 2013," study leader Justin Lessler told IBTimes UK.

"If vaccination rates remain low, measles outbreaks are inevitable, but they may be smaller and more localised than the large outbreak we considered. However, vaccination can virtually eliminate the risk of measles."

During crises, however, vaccination rates fall and in countries affected by Ebola, many children have missed out.

The team used data-driven models to estimate the potential measles outbreak risk, attack rates and mortality rates from a 75% disruption to health care services in Ebola-stricken countries. They also looked at different reduction rates, but 75% was most in line with reports.

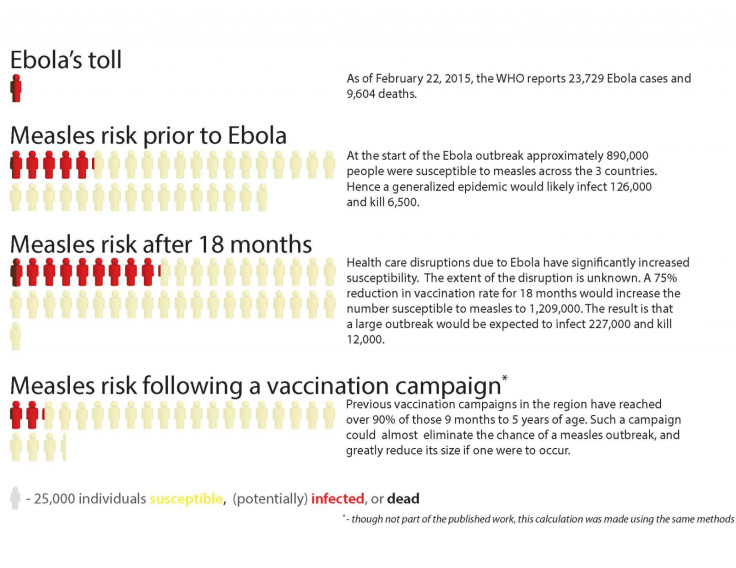

Currently, over 24,000 people have been infected by Ebola and almost 10,000 have died. In the study, researchers found that before the Ebola outbreak, there were 778,000 children between nine months and five years old in the three nations who had not been vaccinated against measles. After 18 months of Ebola disrupting normal services, researchers estimate there will be 1,129,000 unvaccinated children.

Prior to the outbreak, scientists say about 127,000 children would get measles in the event of an outbreak. After 18 months of Ebola, however, this figure is raised to 227,000. Of these, they estimate there would be up to 16,000 deaths.

Lessler said: "I was surprised at how high the case fatality rates to measles had been in previous humanitarian crises, and by the implications of that for these countries. Strengthening health infrastructure in general and maintaining strong partnerships between local and international health communities, even when there is not a crises, is key. Limited resources both locally and internationally are a big challenge. Improvements to routine vaccination and a vaccination campaigns to make up for the Ebola related setbacks could virtually eliminate the risk from measles."

Lessler said deciding when to vaccinate is a balancing act for countries affected by Ebola and local and international officials should best decide when a campaign should be carried out – this, he thinks, will likely take place in about a year if Ebola cases continue to decline.

Another problem facing authorities once a campaign is launched, however, is the mistrust of health workers that has grown among Ebola-hit communities. "It is a big concern. If people are fearful of workers coming into their communities or don't trust they are administering a safe and effective vaccine, then a vaccination campaign could fail to improve immunity to vaccine preventable diseases," said Lessler.

Speaking about the study findings, he added: "It could be a long time before the health care systems in the region recover from this."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.