Poland's Holocaust bill: The 'Polish death camps' controversy explained

Poland's president says he will sign a bill outlawing suggestions the Polish nation or state was complicit in Nazi crimes.

Poland's president says he will sign a Holocaust bill into law, despite protests from Israel and the United States. The measure would impose fines or prison sentences of up to three years for suggesting "publicly and against the facts" that the Polish nation or state was "responsible or complicit in the Nazi crimes committed by the Third German Reich".

However, President Andrzej Duda has said he will ask the country's constitutional court to evaluate the bill and suggest possible amendments.

Poland's right-wing government says the law is necessary to protect the reputation of its citizens and make sure they are recognised as victims not perpetrators of Nazi aggression during World War Two. Poland has long objected to the use of phrases like "Polish death camps" to describe Auschwitz and other camps.

Poland has a point: the death camps were not Polish. The concentration camps were built and run by the Nazis in an area of Poland that had been annexed to the Third Reich – and as such, they were on German soil.

Unlike other countries occupied by Germany at the time, there was no collaborationist government in Poland. The prewar Polish government and military fled into exile, except for an underground resistance army that fought the Nazis inside the country.

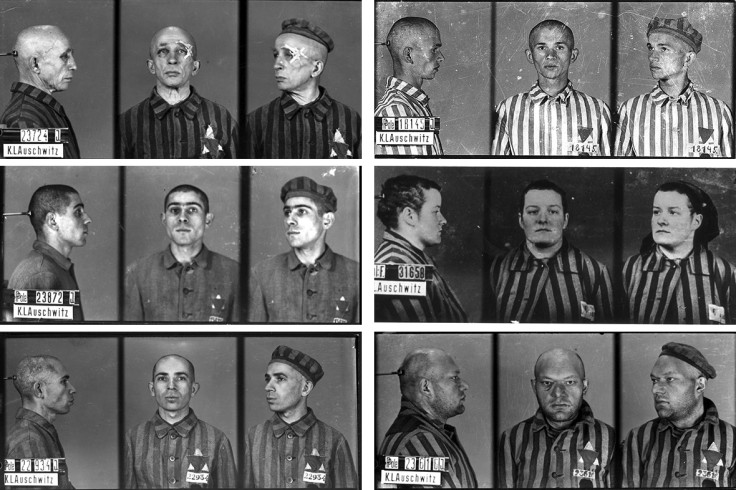

Poland, which had Europe's biggest Jewish population when it was invaded by both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union at the start of World War Two, became ground zero for the "final solution", Hitler's plan to exterminate the Jews of Europe.

More than three million of Poland's 3.2 million Jews were murdered by the Nazis, accounting for about half of the Jews killed in the Holocaust. Jews from across the continent were sent to be killed at death camps built and operated by Germans in what today is Poland, including Auschwitz, Treblinka, Belzec and Sobibor. According to figures from the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Nazis also killed at least 1.9 million non-Jewish Polish civilians.

The Israeli government in the past has supported the campaign against the phrase "Polish death camps," but it has strongly criticised the new legislation. Israel, along with several international Holocaust organisations and many critics in Poland, argues that the law could have a chilling effect on debating history, harming freedom of expression and leading to a whitewashing of Poland's wartime history.

Critics of the new law say it will backfire. Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Alex Storozynski, writing for Reuters, says the law "will not suppress painful realities or opposing views. It will do the opposite. It already has. Usage of the phrase 'Polish Death Camps' has skyrocketed on the Internet."

David Harris, executive director of the American Jewish Committee wrote, "Polish leaders ought to withdraw the legislation and focus on education, not criminalisation, about inaccurate and harmful speech."

Storozynski writes: "As the son of a decorated Polish soldier who fought Nazi Germany and a Polish mother who was imprisoned in a German work camp, it pains me when people call Auschwitz a 'Polish Death Camp'. It had a German motto – 'Arbeit macht frei' (work sets you free) – and German sentries and German Shepherds guarded it. It was a German camp in Nazi-occupied Poland."

Poland played no part in the Holocaust. Indeed, as Storozynski writes, there is archival evidence that "the exiled Polish government's goal was to stop the Holocaust. In 1942 it published a report in New York on 'The Mass Extermination of Jews In German Occupied Poland'. America and its allies turned a blind eye toward the report."

But how about the Poles living near the concentrations camps? Surely they knew what was happening? In 2015, as the 70th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz neared, Reuters interviewed four Polish women who had grown up in the town of Oswiecim, near Auschwitz. How did their parents go about their daily business when such inhumanity was taking place just the other side of a barbed wire fence? How much did they know of what was going on?

"Of course people knew what was going on," said Bogumila, who lived through the occupation as a child. (The women declined to give their family names.) She recalled how as a small girl, she saw prisoners beaten by Nazi guards and watched with her mother the distant glow of the crematorium fires of Auschwitz. "Everyone sat in their homes in silence, windows shut as tightly as possible," she said.

The mass extermination of prisoners and the incineration of thousands of bodies, she said, were no secret. Some former residents have described having to live with the stench from bodies being incinerated at Auschwitz, but keeping quiet to survive. Survival was uppermost in the minds of most of the town's population. "Most of them did nothing, because they were scared," said Bogumila.

Some Poles risked their lives trying to help. Today, Poland boasts the highest number of rescuers who were granted the Righteous Among the Nations title by the Israeli Holocaust research institute Yad Vashem, with 6,706 Poles officially recognised for their efforts to save Jews.

But with Jews making up around 10 percent of the country's pre-war population, anti-Semitism was also rife among Poles. Some pointed out Jews to Nazi soldiers. Some also tried to benefit from the situation financially, either by trading information to the Germans, or by blackmailing Jews in hiding. This was punished by death by the Polish underground. Some Poles also benefited from the death of Jewish countrymen by acquiring their property.

Israel says the law would enable Poland to whitewash the role of Poles who killed or denounced Jews to Germans during the German occupation of Poland during World War Two.

A leading figure in the Jewish American community has criticised Poland's handling of its new Holocaust law. Malcolm Hoenlein, the executive vice chairman of the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organisations, says Poland has made an "issue" out of its people's actions during the Holocaust and is denying the truth.

He says that while Poles who helped save Jews during the Holocaust should be recognised, Poland should also acknowledge that many Poles were complicit in aiding the Nazis. "It is not credible to engage in the denial," Hoenlein said. He says it would be better if Poland said "there was evil done. We recognise it."

Defending the law, Duda said the law will not block Holocaust survivors and witnesses from talking about crimes committed by individual Poles. "We do not deny that there were cases of huge wickedness," he said in a speech.

President Duda said the bill would protect Poland's interests "so that we are not being slandered as a state and as a nation. But it also takes into account the sensitivity of those for whom remembering the Holocaust is extremely important." He added that he would ask the Constitutional Tribunal for a number of clarifications about the bill. Those would likely be issued after it goes into effect. The legislation provides exemptions for research and art.

Israel said it hopes Poland will amend the bill. Israel's foreign ministry said in a statement on Twitter that Israel hoped that before it was finalised "it will be possible to agree on introducing changes and amendments to the law".

On Monday (5 February), Israel's education minister had said he was "honoured" Poland had cancelled his visit to Warsaw this week because he refused to back down from condemning the bill. "The blood of Polish Jews cries from the ground, and no law will silence it," Naftali Bennett later said in a statement.