Portia Antonia Alexis On Economic Inequality, Social Mobility, And the Future Of Global Wealth Distribution

Economic Expert Portia Antonia Alexis is a leading voice within income inequality, wealth distribution and social mobility research.

Economic Expert Portia Antonia Alexis is a leading voice within income inequality, wealth distribution and social mobility research.

Portia Alexis is a 'humanist', and according to her we all are.

The pursuit of her history is key to Portia Antonia Alexis' passion for her research area: income inequality, social welfare and social mobility. Her recent papers The black minority in wealthy countries and The Social Welfare Meteroffer her the chance to continue her rise as a prominent millennial economist within her field.

Portia has cemented herself as a force to be reckoned with, a recent UN nomination and book deal are all another day's work. Sitting on the chair in front of me she looks otherworldly: her cheekbones are framed by a sweep of immaculate hair; in the golden-hour light she looks luminous, dressed in a navy dress and bow loafers. Her combination of model looks and intellectual power has been monumental in her rise on social media as an 'economic influencer,' the first of this sort of brand.

"Since the petrol shocks and the subsequent slowdown in the growth rate, many people have started fearing a breakdown of the social elevator. Research in sociology does not necessarily legitimize this fear, but it is far from entirely reassuring,' says Portia.

Her parents were both social mobility success stories going from humble 3rd world beginnings to global industrialists and philanthropists. 'I wanted to become an equestrian and trained extensively," she says. "I still ride, but only for leisure these days.' 'I fell in love with numbers, and my father told me I could be anything I wanted in the world, but I must give back to it. I used my love of mathematics to analyse the issues I saw every day.'

'My journey began when I started volunteering at 18. I worked as a victim support worker for the Metropolitan Police. After a training course, I became a youth counsellor and I realised there was more to what determines a person's success than meets the eye. From then on my life's work began.'

In the U.S. and the U.K., if downgrading is more a fear than a reality for the middle classes, they must continuously make more efforts to maintain their position in society. "I was intrigued to find that studies on economic mobility suggest that an individual's income depends strictly on that of his parents. Contrary to what one might tend to think a priority, intergenerational mobility is higher in certain developed countries such as France than in the United States or the United Kingdom.'

She continues, 'Also, international comparisons show a negative correlation between income inequality and intergenerational mobility: the higher the difference, the more individuals tend to reproduce the same situation as their parents in the income scale. It is what Alan Krueger calls the "Great Gatsby curve," says Portia, as her brow suggests concern and curiosity simultaneously.

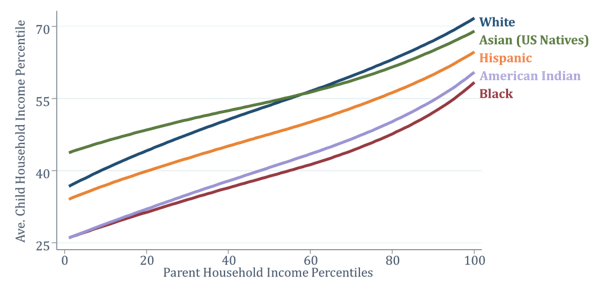

Race is an area she is micro focused on and how the trajectory of minority groups varies in different wealthy countries. Currently she is comparing the USA and the UK with an emphasis on black minorities. Speaking on the probability of social mobility in the USA for black minorities, she states, 'Growing up in high-income families in the United States does not protect against these disparities: black children born in the highest income quintile are as likely to stay there as they are in the lowest quintile. Conversely, white children born to high-income families are five times more likely to stay there than to fall into the lowest-income quintile.'

She shows me a graph and some notes pinpointing the information. 'The "American dream" is out of date: most Americans are not sure that their children will be better off than they are. It is entirely consistent with the evolution of wage dynamics in the United States in recent decades. While the real wages of 30-year-old Americans increased at an average annual rate of 1% between 1965 and 1995, they only increased on average by 0.6% per year between 1985 and 2015.'

Research shows me that the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) confirms she is indeed right. Social mobility is even less in the United States than in Europe. When a father is among the most deficient 20% of Americans, there is a 40% chance his son will not do any better than 30% in the U.K.

Not taking attention away from the UK she states issues are similar on both sides of the pond. 'Precariousness has worsened for all workers in the U.K. in the past seven years. It concerned 3.2 million in 2016, 11% more on average than in 2011. Employers offer temporary or zero-hour contracts.' She pauses. 'Black employees are also mainly concerned by the proliferation of precarious contracts for the latter, with an increase of 58% in temporary agreements relating to them against a rise of 8% for white employees.'

Most upsetting, she states is that black women in the UK are the most affected: they are 82% more likely than in 2011 to be on a temporary contract, while the increase was 37% for black men.

I asked Portia what key facts she thinks are important to know about social mobility as she munched on the end of her pen. She said, "Firstly, we must understand that 'The decline in absolute upward mobility is mainly due to the increase in income inequality and the slowdown in economic growth. The latter is the primary explanatory factor in most countries; in the United States and, to a lesser extent, in the United Kingdom.'

"Secondly, on the other hand, it is the rise in income inequality that explains the decline in social ascent. The prospect of further weak growth and widening income inequality suggests that this dynamic will continue."

What does she worry about? She looks downcast. "It is the rise in income inequality that explains the decline in social ascent. The prospect of further weak growth and widening income inequality suggests that this dynamic will continue. And if economic growth accelerates unexpectedly steadily, this might not be enough to encourage social ascent: the increase in absolute upward mobility could necessarily go through a decline in inequality.'

Portia's Young Adult Book Series Will Be On The Shelves in February 2022.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.