Rare Brain Worms from Far East Discovered in UK for First Time Living in Man's Head

Extremely rare brain worms have been discovered in the UK for the first time, having been living in a man's head for four years.

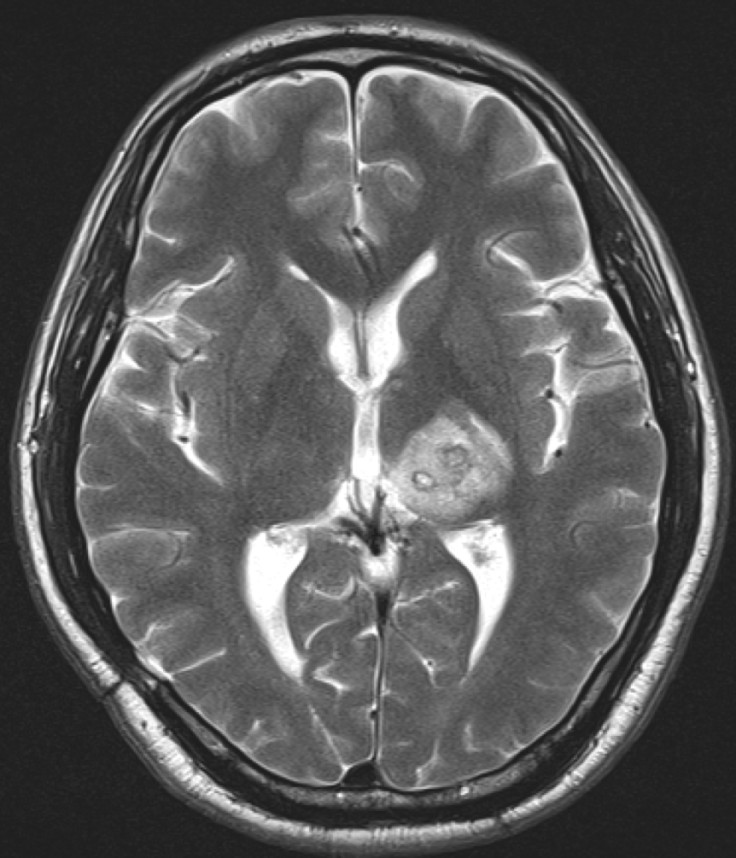

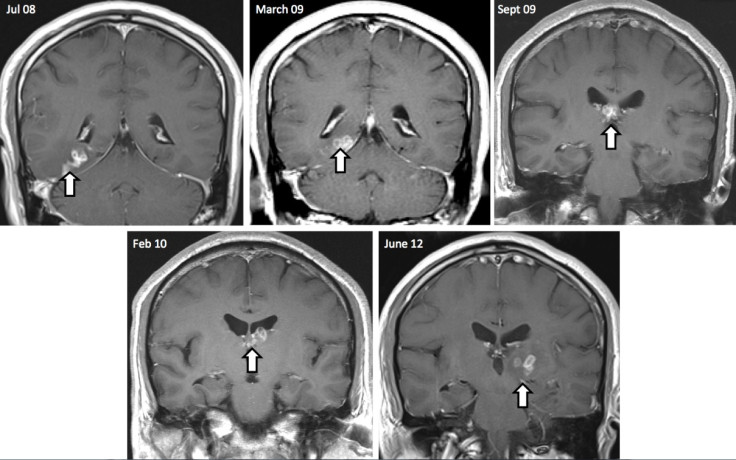

The tapeworm, Spirometra erinaceieuropaei, was 1cm long when it was removed by doctors. It had travelled 5cm from the right side of the brain to the left.

Globally, only 300 cases of the brain-dwelling worm have been diagnosed since 1953 and this was the first to be identified in the UK.

It causes sparganosis – inflammation of the body's tissues, which can lead to seizures, memory loss and headaches. It is thought people become infected by consuming tiny infected crustaceans from lakes, eating raw meat from reptiles and amphibians and by using frog poultice – a Chinese remedy for sore eyes.

Effrossyni Gkrania-Klotsas, study author from the Department of Infectious Disease, Addenbrooke's NHS Trust, said: "We did not expect to see an infection of this kind in the UK, but global travel means that unfamiliar parasites do sometimes appear."

The man has recovered from the operation and is well and scientists have now been able to discoverer the genetic secrets of the worm, offering new opportunities to diagnose and treat the parasite.

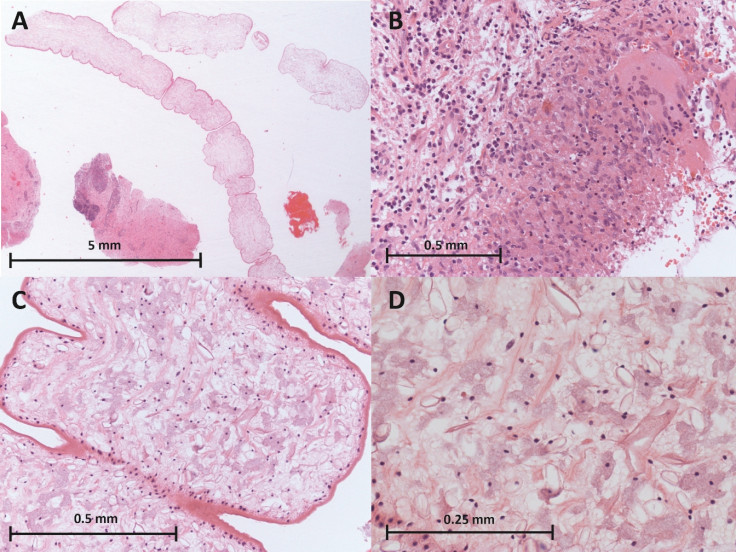

Hayley Bennett, first author of the study from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, said: "The clinical histology slide offered us a great opportunity to generate the first genome sequence of this elusive class of tapeworms. However, we only had a minute amount of DNA available to work with – just 40 billionths of a gram. So we had to make difficult decisions as to what we wanted to find out from the DNA we had."

Published in the journal Genome Biology, the sequence showed the species was one of the more benign of the two sparganosis-causing brain worms. The brain worm's genome is 10 times large than other tapeworm genomes and about the third the size of a human's. It appears the increased size helps the parasite break up proteins and invade its host.

Researchers are now able to diagnose the worm through MRI scans, but more work is needed to identify its vulnerabilities. They also said the information gained can be matched with their work in global travellers' infection, to give a better insight into what infections people can get in specific destinations.

Matt Berriman, senior author and member of Faculty of the Sanger Institute, said: "For this uncharted group of tapeworms, this is the first genome to be sequenced and has allowed us to make some predictions about the likely activity of known drugs.

"The genome sequence suggests that the parasite is naturally resistant to albendazole – an existing anti-tapeworm drug. However, many new drug targets that are being explored for other tapeworms are present in this parasite and could offer future clinical possibilities."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.