Ray Abernathy Obituary: The PR Man Who Gave US Workers a Voice and Broke 'Mad Men' Stereotypes

Corporations have their minions who plot the messages that sell products. They work for the Madison Avenue agencies, popularised the two martini lunches, and are the legend of "Mad Men."

When there is a mining disaster, a chemical plant explosion, or a catastrophic event causing workplace death, they are the people behind the scenes spinning the message that will stanch the bleeding on brand and reputation.

They are the ones who scheme to focus heads and eyes away from that which merits attention and the light of day.

And then there is Ray Abernathy who - until his passing on 12 September - did the opposite.

Exposing Working Conditions

Working with some of the largest labour unions in the United States, Abernathy and his wife Denise Mitchell, orchestrated campaigns that exposed the plight of workers and the consumers they served.

From discriminatory working conditions for low-paid nursing home workers in the gulf coast of Texas, to a campaign to expose substandard elderly care at one of the nation's giant nursing home chains, Abernathy & Mitchell were the antithesis of Madison Avenue.

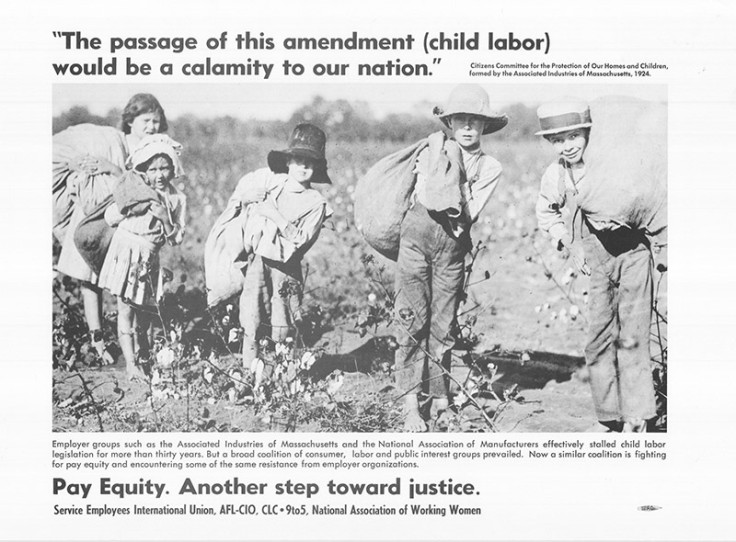

They taught labour unions to deliver the word that the mistreatment of workers has a rippling effect, impacting consumers and shareholders, and through their messaging, workers without a voice were heard.

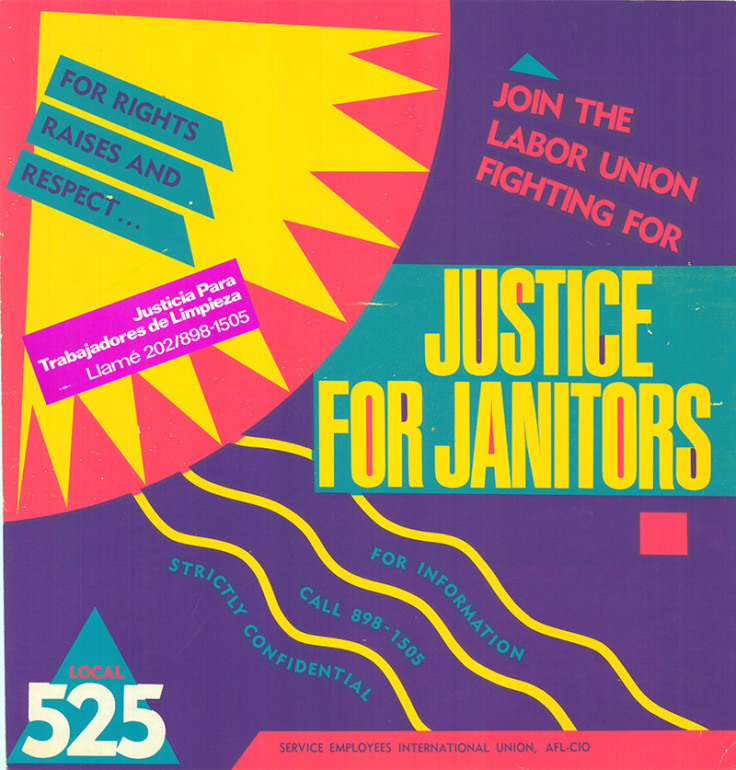

In 1980, Abernathy & Mitchell took on work for the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) - a union built around the representation of low paid janitors and nursing home employees.

At the time, SEIU's size was dwarfed by the Steelworkers, the Auto Workers and the other industrial unions.

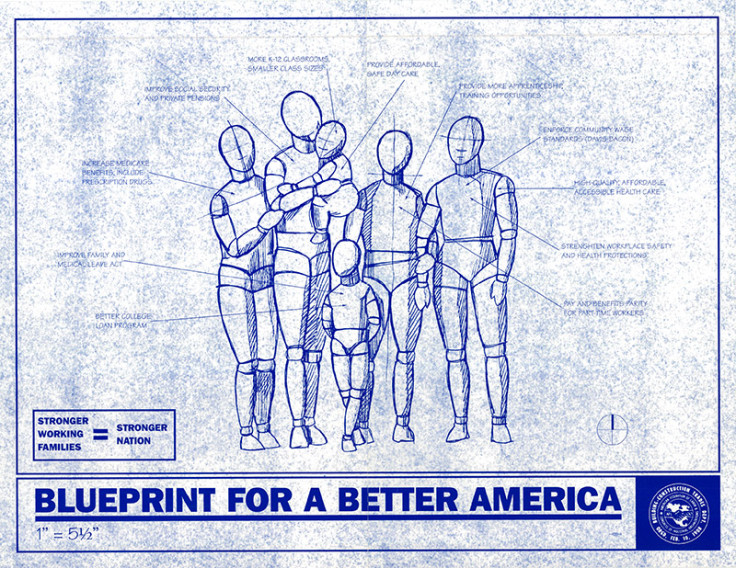

Bringing the sophistication of Madison Avenue to strikes and organising campaigns, Abernathy & Mitchell produced video pieces on the working lives of janitors in Pittsburgh, nursing home workers in Los Angeles and public employees throughout the nation.

They developed radio commercials that told the plight of workers in their own voices and designed newspaper ads bringing the faces of the lowest paid workers to the breakfast table.

They took the union's tabloid newspaper and turned it into a glossy magazine with human interest stories that made workers feel good about their union and made others want to join in.

As giant companies developed new paradigms to circumvent traditional employment relationships and vulnerability to union organising and bargaining table power, Abernathy was part of, and helped promote, a growing culture within the labour movement of progressive trade unionists committed to exploring ways to restore the balance of power between labour and management.

He was not just about the message; he immersed himself in the substance by encouraging litigation, legislation and "out of the box" efforts to vindicate worker rights.

When Abernathy first began work for SEIU, mention of the union's name in major papers including the New York Times was a rarity.

Yet, by the late 1980's the union had grown in size and stature, becoming a leader among labour unions and a force in American politics. And through its trajectory, Abernathy played a role behind the scenes, crafting the message and working with others to formulate a public interest agenda reaching beyond workplace issues.

In 1995, SEIU's President, John Sweeney, parlayed the union's success into election as President of the AFL-CIO. Ultimately, Sweeney was replaced at SEIU by Andy Stern who cut his teeth in the labour movement as leader of the Pennsylvania Social Services Union, another Abernathy client.

Today, of course, the SEIU is one of the largest unions in the United States. It is a union that played an integral role in the election of Barack Obama.

My Mentor

I first met Abernathy over three decades ago. Two minutes out of college, I was a communications staffer for the 47 thousand-member New York State Public Employees Federation, a union representing professional, scientific and technical employees of the State of New York.

Abernathy was a transplanted Washingtonian who migrated from Atlanta, where he had played a role in the election of Jimmy Carter as Governor and had dabbled in Atlanta politics. He was a quick witted word craftsman with a wide streak of cynicism.

When Ray helped get me promoted to Acting Director of Communications, I thanked him and queried as to what he saw in me. He told me that my salary fit within the union's budget.

That was Ray. We would work through the night by phone with me at the Union's printer and Ray back in Washington editing the union's newspaper word for word. When the New York Times erred in its reporting of the union's new contract with the State of New York, Ray walked me through the strategy to convince the Times' young Albany reporter, E.J. Dionne, to print a correction. That was also Ray.

When I went to law school, Ray kept me employed, involving me in work for the meat packers, nursing home workers, and public employees in California.

During the summer of 1984, sitting in his small "shop" on DeSales Street in Washington, DC, we did research and wrote a white paper for release by SEIU on the perils of asbestos in public schools. The paper led to litigation and ultimately the passage of the Asbestos Hazard Emergency Act, a law protecting workers and students from the hazards of asbestos.

That summer he also sent me to California and challenged me to get New York Times reporter Maureen Dowd to write about the unionised janitors who swept the floor of the 1984 Democratic National Convention in San Francisco. That was Ray giving visibility to those not on stage or noticeable to a national TV audience.

While I was still in law school, Ray made me part of an effort to organise Atlanta police into a real labour union and he immersed himself in a legal strategy to secure dues deduction.

He selected former Assistant Atlanta City Solicitor, Henry Bauer, to bring a suit against the City under the Fourteenth Amendment. Today, the union stands as a vibrant reminder of Ray's efforts.

In the early days --before lap tops and desktops -- he would peck out his written work on an IBM Selectric; sometimes cursing at the machine when his fingers hit the wrong keys.

I remember him doing this in a stark Beaumont, Texas union hall in the heat of the summer of 1985 when we were working on a strike of low-paid -- predominantly minority -- nursing home employees.

Back in Washington, he would sit in meetings with union organisers and lawyers and interchangeably talk organising and legal strategy. That was Ray too.

Over the past few years I lost touch with Ray. But like any mentor, the lessons I learned from him and my experiences working with him will never be forgotten.

He gave me my first exposure to representing workers and when I left the union to attend law school, he wrote a piece in the union newspaper noting my impending departure with words of encouragement that he hoped I would return as a labour lawyer.

I did; spending my first five years out of law school as a Washington based attorney for SEIU.

Ray Abernathy was not a lawyer, but through his words he advocated in a court of public opinion on behalf of countless workers whose voices had gone unheard.

Ray's own voice will be sorely missed, but his impact on the labour movement will endure.

Reuben Guttman, heads the international whistleblower practice and runs the Washington, DC office of the law firm of Grant & Eisenhofer . He is a Senior Fellow and Adjunct Professor at the Emory University School of Law Center for Advocacy and Dispute Resolution and has taught for the Center in China and Mexico. He is a founder of the website whistleblowerlaws.com.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.