RemoveDebris: First mission to test space junk removal systems set for launch next year

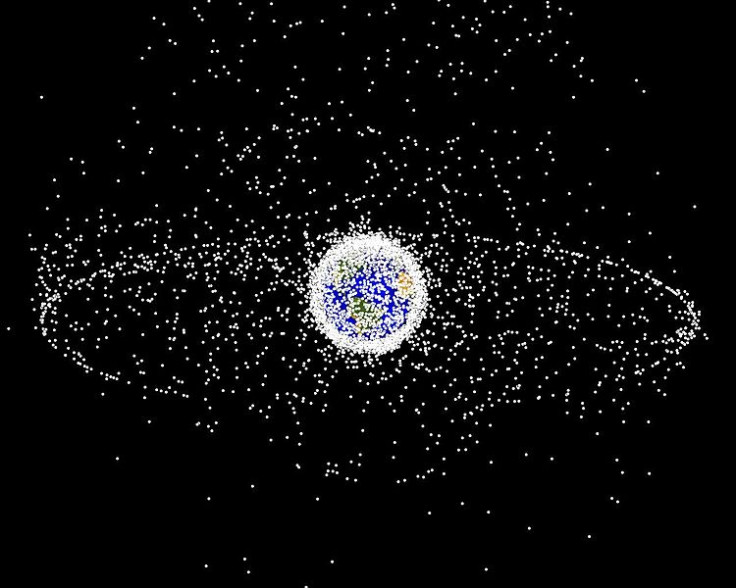

Over 7,000 tons of space debris orbit Earth and at present there is no way to get rid of it.

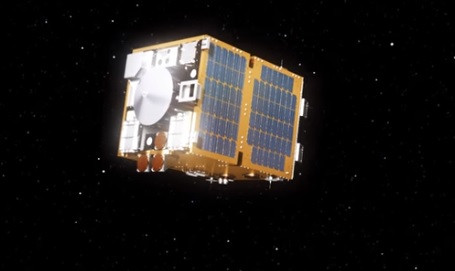

The world's first mission to test out a space junk litter-picker is set to be launched next year. Led by the Surrey Space Centre, the RemoveDebris mission will see an international team of scientists launch a spacecraft that can catch pieces of space junk with a net then drag it back down towards Earth, where it will burn up in the atmosphere.

The team behind the mission presented their plan at the Royal Society Summer Science Exhibition in London. Dr Jason Forshaw, from the Surrey Space Centre and project manager on the RemoveDebris mission, told IBTimes UK: "All about 7,000 tons of junk currently floating around in space. There's so much up there – dead satellites, flecks of paint etc. Our aim is to deal with this issue and get rid of it."

The mission will be the first to test debris removal technology in space. RemoveDebris will deploy small bits of artificial junk that it can catch with its harpoon and net. They also plan to test the de-orbiting devices that will dispose of the debris. Once the technology has been successfully tested, missions to capture existing space debris can be launched.

Aaron Knoll, Lecturer in Plasma Propulsion at Surrey Space Centre, is involved in moving the litter-picker around in space. To rendezvous with the space junk, the spacecraft must adjust its orbit to match that of the debris. "The objects are moving really fast – about 7.5km every second – mind-bogglingly fast," he said.

Space debris and the Kessler Syndrome

There are currently thousands of pieces of space debris orbiting Earth. Widely popularised in the Oscar-winning film Gravity, these pieces of space junk have the potential to cause huge damage to satellites and spacecrafts – both those being kept in Earth's orbit or those travelling farther afield.

Since the 1960s, the amount of space junk has been increasing at an immense rate. In 2011, a report by the US National Research Council said we are getting close to the point where there will be too much space debris to carry out a successful launch.

First proposed by Nasa's Donald Kessler in the 1970s, this tipping point is now known as the Kessler Syndrome. It says there will come a time where the density of space junk will be so high it will cause more collisions, resulting in even more space junk. This ricochet effect could make future missions extremely dangerous, if not impossible.

"In order to know exactly where the space debris is located and match your orbital speed with the orbit of the object, then to rendezvous with it in close proximity on such a fast moving object, it's incredibly difficult. Also there's the whole problem of the orbital dynamics... things behave very differently in space and it becomes quite a problem."

However, Knoll said he is confident the tests will be successful. "Because it's a space mission and every part of the mission is critical, you have to qualify and test every aspect of the mission before the flight, so that's what we're going through at the moment," he said.

Forshaw said once they have successfully tested out the technology on smaller items, the nets and harpoons can be scaled up to capture larger pieces of space debris. "We believe space is part of our overall environment," he said. "A lot of people think of rainforests and oceans as part of Earth's environment, but very rarely people think of space as being part of it.

"What we need to do is to clear up this junk so it doesn't impede future spacecraft being launched into different orbits. Eventually if we keep having junk launched into all these orbits, we're going to end up with lots of collisions in the future and it's going to cost more than if we act now and start dealing with this problem... We've got to get rid of this junk in these areas because there's a high risk of collision and there have been collisions in the past. They will keep increasing."

Knoll added: "I think everything that goes into space going forward should have the capability of removing itself. It's responsible behaviour from people launching things into orbit. But for those things that were launched previously, say since the 1960s, there should be missions to go up, capture and de-orbit to keep the space environment clean for generations to come."

The RemoveDebris test mission will be launched early in 2017. Funding for the project comes from the European Commission and partner organisations include Airbus DS, Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd and CSEM in Switzerland.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.