RIP E.T. – Alien life on most exoplanets dies young

Aditya Chopra, Australian National University and Charley Lineweaver, Australian National University

Astronomers have found a plethora of planets around nearby stars. And it appears that Earth-sized planets in habitable zones are probably common.

So, with tens or even hundreds of billions of potentially habitable planets within our galaxy, the question becomes: are we alone?

Indeed, the search for alien life has become the holy grail for the next generation of telescopes and space missions to Mars and beyond. But could our search for E.T. be naively optimistic?

Many scientists and commentators equate "more planets" with "more E.T.s". However, the violence and instability of the early formation and evolution of rocky planets suggests that most aliens will be extinct fossil microbes.

Just as dead dinosaurs don't walk, talk or breathe, microbes that have been fossilised for billions of years are not easy to detect by the remote sampling of exoplanetary atmospheres.

Gaian Bottleneck

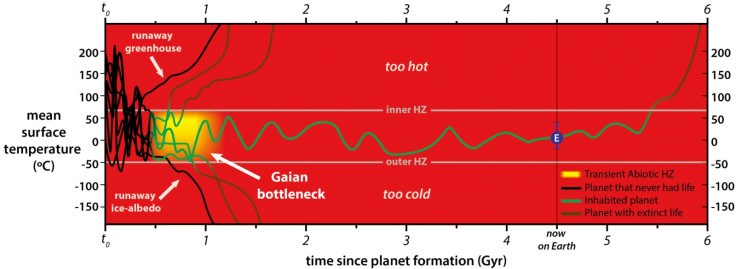

In research published in the journal Astrobiology, we argue that early extinction could be the cosmic default for life in the universe. This is because the earliest habitable conditions may be unstable.

In our "Gaian Bottleneck" model, planets need to be inhabited in order to remain habitable. So even if the emergence of life is common, its persistence may be rare.

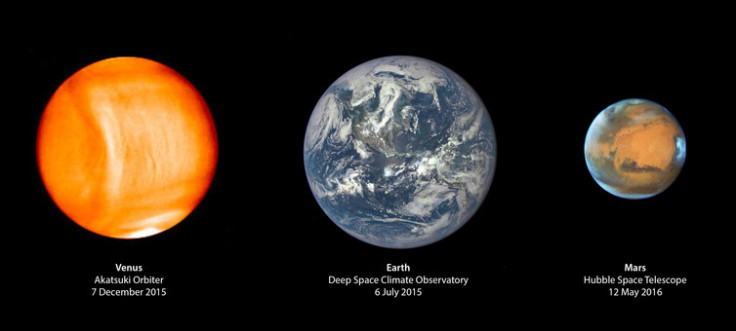

Mars, Venus and Earth were more similar to each other in their first billion years than they are today. Even if only one of the planets saw the emergence of life, this era coincided with heavy bombardment from asteroids, which could have spread life between the planets.

But about 1.5 billion years after formation, Venus started to experience runaway heating and Mars experienced runaway cooling. If Mars and Venus once harboured life, that life quickly went extinct.

Even if wet rocky Earth-like planets are in the "Goldilocks Zone" of their host stars, it seems that runaway freezing or heating may be their default fate.

Large impactors and huge variation in the amounts of water and greenhouse gases can induce positive feedbacks cycles that push planets away from habitable conditions.

The carbonate-silicate weathering cycle, which provides the major negative feedback to stabilise Earth's climate today, was probably inoperative, or at least inefficient, until about 3 billion years ago.

However, life on Earth may have had the fortuitous ability to create stability by suppressing the positive runaway feedback loops and enhancing the negative feedback loops.

We should probably thank the unpredictable evolution of microbial communities our planet hosted early in its history for saving us from runaway conditions that would make Earth too hot or too cold for us to live.

As soon as life became widespread on Earth, the earliest metabolisms began to modulate the greenhouse gas composition of the atmosphere. It is no coincidence that methane, carbon dioxide, hydrogen and water are all potent greenhouse gases and also the reactants and products of metabolic reactions of the earliest microbial mats and biofilms.

The emergence of life's ability to regulate initially non-biological feedback mechanisms (what we call "Gaian regulation") could be the most significant factor responsible for life's persistence on Earth.

Abiotic habitable zones are transient

The Earth is not the only planet in our galaxy with liquid water on its surface and energy sources and nutrients to enable life to form.

Although the universe is filled with stars and planets conducive to life, the absence of any evidence for alien life suggests that even if the emergence of life is easy, its persistence may be difficult.

Our work challenges conventional views that physics-based habitable zones provide stable conditions for life for many billions of years.

Although, the cottage industry of habitable zone modellers can turn various knobs that control atmospheric and geophysical properties to stabilise planets over short-timescales, they have mostly ignored the role of biology in keeping planets habitable over billions of years.

This is in part because the complexities of interactions between microbial communities that keep ecosystems stable are not sufficiently understood.

We hypothesise that even if life does emerge on a planet, it rarely evolves quickly enough to regulate greenhouse gases, and thereby keep surface temperatures compatible with liquid water and habitability.

Maintaining life on an initially wet rocky planet in the habitable zone may be like trying to ride a wild bull. Most riders falls off. So inhabited planets may be rare in the universe, not because emergent life is rare, but because habitable environments are difficult to maintain during the first billion years.

Most life dies young

Our suggestion that the universe is filled with dead aliens might disappoint some, but the universe is under no obligation to prevent disappointment.

We should not expect technological or spacefaring civilisations because there is no evidence that biological evolution converges to human-like intelligence. And subjective philosophical notions of life in the universe should not inform our estimates of the probability of life beyond Earth.

Superficially, these ideas seem to undermine the motivation for SETI and the recently announced Breakthrough Listen project.

Nevertheless, we support SETI because when we explore new regions of parameter space, we often find the unexpected.

In his book Pale Blue Dot, Carl Sagan reminded us that "in our obscurity, in all this vastness, there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves".

In the two decades since it was published, we've learnt that our cosmic backyard is littered with pale dots, probably in many colours of the rainbow. As we embark on the adventure of exploring our galactic neighbourhood with bigger and better telescopes, we may find only spooky planets haunted by long dead microbial E.T.s.

Aditya Chopra, Post-doctoral Research Fellow, Australian National University and Charley Lineweaver, Researcher at Research School of Astronomy and Astrophysics and the Research School of Earth Sciences, Australian National University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.