Robin Williams' Suicide: Media Vultures Risk Triggering Copycat Deaths

The way Robin Williams' death has been reported has been condemned as a horrific and sickening display of the media at its most insensitive and irresponsible.

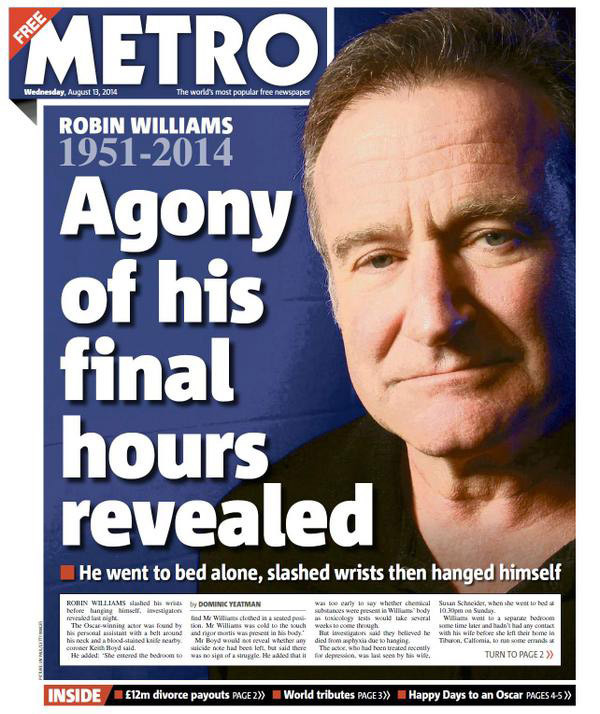

Many newspapers and websites ran front page headlines with Williams' method and means of suicide, describing in gory detail how the actor took his own life.

While news outlets initially celebrated the actor's life and work, while also telling of his long battle with depression, reporters quickly turned into vultures, picking over his corpse looking to get more clicks and sales.

In the UK, the Editors Code clearly states that "when reporting suicide, care should be taken to avoid excessive detail about the method used". This, however, is not enforceable by law so editors have the apparently difficult task of adhering to it because of ethical obligations, rather than legal ones.

.@MetroUK disgraceful front page about Robin Williams. The language used could be highly triggering & the front page suggests glorification

— Matt Woosnam (@MattWoosie) August 13, 2014

The Sun's headline and front page about Robin Williams is absolutely vulgar, they should be ashamed

— Beckie (@BeckayPoole) August 13, 2014

.@Mirror_Editor front page re Robin Williams IS NOT OK!wtf is the matter with you?! pic.twitter.com/jgwcQvg7Lz http://t.co/jgwcQvg7Lz

— laura mcdonnell (@mcdonnell_laura) August 12, 2014

The Press Complaints Commission (PCC) can and does bring cases against publications that report suicide irresponsibly, however many are not upheld because of what appears to be a checklist on sensitivity.

For example, a case was brought against the Sunday Times following the Bridgend suicides between 2007 and 2009. In an article called 'Death Valley' the newspaper ran images of the victims next to a large picture of a noose. The complaint was not upheld.

In its ruling the PCC said: "The newspaper acknowledged that the relatives of those who had died might be upset by the juxtaposition of a noose and pictures of the dead. However, it argued that the whole point of the graphic introduction was to highlight the apparent happiness of the young people in the pictures with the harsh reality of what they had done. It maintained that it had conducted a serious investigation, and had dramatically portrayed it in a way that avoided glamorising suicide."

Research on copycat suicides following celebrity deaths is extensive, with studies showing that the way media outlets report a celebrity's suicide directly affects the number of copycat deaths.

After Marilyn Monroe's death in August 1962, there was a 12% increase in suicides. Sociologist Steven Stack found that suicides of celebrities are 14 times more likely to result in a copycat effect than non-celebrities. He said this was likely because there is a greater degree of identification with the victim.

Those who argue that freedom of speech provides the right to treat Williams' death as a gory spectacle are just plain wrong.

In Taiwan in 2005, the high-profile actor MJ Nee was found dead, having taken his own life. Coverage of his death was extensive, with reports appearing hourly for over two weeks. Newspapers used sensational statements, providing graphic details on the method – hanging – as well as images of the rope, the tree and his body.

In the four weeks that followed, there was a 20% increase in the number of suicides, with those using hanging as a method also increasing.

Suicide contagion is not new. One of the first reported cases dates back to the 1700s when Johann Wolfgang von Goethe published The Sorrows of Young Werther. In the novel a young man takes his own life because of unrequited love. The number of copycat suicides following its release surged.

The Samaritans, the World Health Organisation and the Centre for Centre for Suicide Prevention all provide similar guidelines clearly stating how suicide should be reported. The latter's set out the following list of what journalists should not do:

- Presenting simplistic explanations for suicide

- Engaging in repetitive, ongoing, or excessive reporting of suicide

- Providing sensational coverage of suicide

- Reporting 'how to' descriptions of suicide

- Presenting suicide as a tool for accomplishing certain ends

- Glorifying suicide or persons who commit suicide

- Focusing on the suicide completer's positive characteristics

The coverage of Williams' death can be viewed as contravening several of these points.

Conversely - and even more disheartening to someone working in the media - research also shows that responsible reporting of suicide can reduce the number of contagion deaths. Increasing awareness of the link between mental health problems and suicide, as well as providing contact details for support groups, such as the Samaritans, helps to reduce deaths.

In Bridgend, the media was accused of excessively reporting the deaths and leading to copycat suicides. However, few were ever held to account. Following an investigation, the PCC found: "The picture that emerged was less a case of repeated individual breaches of the Code, than a cumulative jigsaw effect of collective media activity, which became a problem only when the individual pieces were put together."

However, it also adds: "There can be no hard rules in such subjective areas. These and similar measures can only be discretionary."

The conclusion that a "jigsaw effect" of reporting, rather than a direct violation by one individual publication, was to blame is farcical. When coupled with the additional note, it becomes pointless.

Those who argue that freedom of speech provides the right to treat Williams' death as a gory spectacle are just plain wrong. It is morally incomprehensible and serves only to highlight the gaping ethical flaws that still dog the media industry as a whole.

People feeling distressed who feel the need to talk to somebody should call the Samaritans on 08457 90 90 9008457 90 90 90 or email jo@samaritans.org.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.