Saudi Arabia: King Salman's vision is ultra conservative – and Saudis love him for it

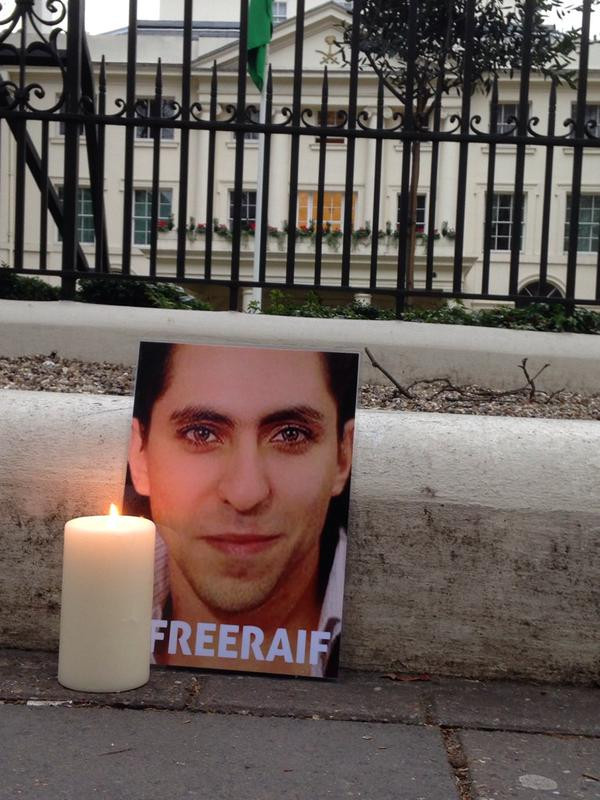

Saudi Arabia is a difficult place to be a liberal – just ask Raif Badawi, the jailed blogger sentenced to 1,000 lashes for insulting Islam – it is an equally difficult place to be a liberal ruler.

Former king Abdullah Bin Abdulaziz was hailed worldwide for the reforms that he initiated in the decade before his death in January, however for many of the clerics and uber-conservatives who dominate Saudi political and social life, he will not be missed.

"I think although most people in the west welcomed what Abdullah did, it was profoundly unpopular in Saudi Arabia," said Robert Lacey, historian and author of Inside The Kingdom, an authoritative 2009 book about the country and its politics.

One of Abdullah's legacy projects was the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST), a mixed-sex science and technology hub near Jeddah that the ageing monarch envisaged as an attempt to put Saudi Arabia on the scientific map.

The multimillion dollar development was also an architectural marvel, winning a number of awards when it opened in 2010 and recruiting staff from across the world. But six months after Abdullah's death, KAUST is "not something that the Saudi authorities like to acknowledge", said Lacey. KAUST declined to be interviewed when contacted by IBTimes UK.

The emergence of the Islamic State was greeted with some sympathy because it fed into an anti-Iranian and anti-Shia sentiment which had been stirred up by Saudi and GCC government rhetoric in the media for years

Abdullah's policy of including 30 women on Saudi Arabia's 150-strong "parliament" – known as the Shura Council – was equally divisive, actually bringing clerics and Islamists on to the streets to call for democracy, albeit only for men. Abdullah's policies were so derided by Islamists that it prompted them to align with liberals in calling for more democracy.

The complex relationship between the Saudi royal family and fanatical Islam dates back to the very foundations of the Saudi state, when Abdullah's grandfather, Ibn Saud bin Abdulaziz, sided with the radical Wahhabi Ikhwan– the Islamic State (Isis) of its day – in order to seize the territory that now makes up Saudi Arabia.

Ever since, successive Saudi royals have had to placate the radical descendants of those religious zealots with both sticks and carrots. The sticks are the occasional crackdowns and jailing of those extremists who shout too loud. And the carrots? The ongoing ban on women driving, the religious police, full-face veils and, for new king Salman bin Abdulaziz, the flogging of Badawi.

But it is not just among the aged, bearded zealots of the villages of the Najd (the central Saudi heartland of Wahhabism) where conservative opinions hold sway. When IS swept out of the deserts of Syria and on to the world stage in 2014, hundreds of young Saudis flocked to join it. Saudi nationals make up one of the largest groups of foreign fighters in Iraq and Syria.

In that, these young fanatics are only following in the footsteps of an earlier generation of fanatics from Saudi that took up the gun and the suicide belt in Bosnia, Iraq, Chechnya and Afghanistan – including Osama bin Laden, a Saudi national and son of one of the kingdom's most prominent businessmen. Saudis, of course, made up 15 of the 19 attackers on 9/11 in New York.

"The emergence of the Islamic State was greeted with some sympathy because [it fed] into an anti-Iranian and anti-Shia sentiment which had been stirred up by Saudi and GCC government rhetoric in the media for years," said Toby Matthiesen, the author of The Other Saudis: Shiism, Dissent And Sectarianism and an expert on contemporary Saudi Arabia.

That anti-Shia sentiment has long found its voice in human rights abuses against Saudi Arabia's estimated 450,000-strong Shia population in the eastern province, where Shi'ite Muslims complain of widespread persecution and which has seen devastating terrorist attacks over the past month.

Shia activists have long warned not just of government persecution but of rising anger and sectarian language coming from radical mosques and extreme Sunni voices.

As for Iran, the Tehran versus Riyadh cold war has been given a bloody lease of life through both the war in Syria – where Iran is backing Bashar al-Assad and Saudi is backing the Sunni militias who are seeking to overthrow him – and in Yemen, which Saudi Arabia is currently bombarding with air strikes in an attempt to oust Shia Houthi rebels.

Saudi Arabia's military venture in Yemen was supported by Western governments early on but the rising death toll, obstruction of aid convoys, military blockade and, most recently, bombing of Unesco-listed buildings while residents were apparently still inside has increasingly garnered negative headlines in the West. Despite that, the war was almost unanimously popular at home.

"[King Salman] is getting an enormous amount of stick in the West for his war in Yemen but he is fantastically popular in Saudi Arabia. It is not just politics – people love it that Saudi is flexing its muscles and socking it to the Houthis," said Lacey.

As for Badawi, while his sentencing has been a major story in the West, it has barely registered in Saudi Arabia. While "Raif Badawi" trended on Twitter in English in mid-June after his sentence was upheld and he was scheduled to receive the next instalment of his 1,000 lashes, it barely registered in Arabic. Analysis of Google Trends by IBTimes UK revealed "Raif Badawi" got three times as much traffic in English as in Arabic. Saudis simply do not care.

Even if they did, it is not Saudi Arabia's small, mostly urban liberal population that King Salman is trying to placate. It is the conservatives both young and old who either support radical groups such as IS or actively join them. The biggest threat to the House of Saud is not liberal bloggers, it is fundamentalist Islam.

"I think Salman felt that Abdullah sacrificed too much of the conservative base [and] one factor in his becoming more conservative is to try and mend that breach [...]. The West goes on about Raif Badawi and liberal bloggers [but] they are irrelevant in the Saudi context," said Lacey.

What matters to them is not what liberals in the West think, but what fundamentalist, potential supporters of ISIS think on the streets of Riyadh

It is not all political. King Salman is known to be more pious than his late brother, and was far more likely to be in the company of clerics than the business elites Abdullah forged alliances with in his 10-year push for development in the kingdom. While Salman has overseen a crackdown on both financing and recruitment by IS in Saudi, he is close to Islamist figures and groups in the kingdom.

"King Salman [has built] on his extensive contacts with various groups in the kingdom which he had forged as governor of Riyadh since 1963, including with Islamist forces. Indeed, he and the new administration that he installed very rapidly seemed to be closer to the Saudi Islamists including to those deemed part of the Muslim Brotherhood," said Matthiesen.

This is a marked departure from the attitude of his brother, who rewarded Egyptian leader General Abdel Fattah al-Sisi with millions of dollars in aid after he overthrew elected president Mohammed Morsi in June 2013. Abdullah's support for the coup in Egypt was unpopular among the millions of Saudis who felt an affinity with the Brotherhood and its rule.

King Salman's lurch towards the traditional means that in a cruel irony, the longer the outcry over Badawi lasts, the longer it is before the blogger is released. The case has parallels with that of Hamza Kashgari, the teenager who was accused of insulting the Prophet Mohammed in 2012 and was subsequently jailed.

Like Badawi, Kashgari's case attracted massive media attention when he attempted to flee to Malaysia before being deported back to Saudi. Unlike Badawi, though, Kashgari was quietly released when the furore died down and he wrote various letters to local clerics apologising for his comments, according to Lacey, who knew the young man's family well.

"That, I am quite sure is just what Salman would love to do with Raif Badawi – but with [...] everybody bleating on about him at every opportunity he has become a hostage to fortune," said Lacey.

"[This] is the last thing that the Saudi foreign ministry wants. They are fully aware of what the West is thinking, but what matters to them is not what liberals in the West think, but what fundamentalist, potential supporters of IS think on the streets of Riyadh."

King Salman's courting of the radical Sunni strain that runs through so much of Saudi society is unlikely to end any time soon, given the resurgence of IS in Iraq and the efforts by the international community to bring Riyadh's main rival, Iran, out of the cold.

The wars in Syria, Yemen and Iraq and the unrest in eastern Saudi Arabia cannot help but have a sectarian identity and it is clear which side of that fence the House of Saud will fall.

At the same time, there has been no attempt under Salman to end the Abdullah-initiated scholarships that saw thousands of young Saudis travel overseas to study, while the opening of the Saudi stock market in June – another Abdullah pet-project – was not torpedoed once the former king died.

Badawi is unfortunate evidence that when change comes in Saudi Arabia, it comes with whispers rather than trumpets.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.