Scottish elections 2016: How left-wing is the SNP?

For now in Scotland, Labour is finished. The Conservatives barely started. And the less said about the Liberal Democrats the better. So the Scottish National Party (SNP) will, bar a shock on 5 May, maintain its tight grip on power in the Holyrood elections for the foreseeable, as they have done since first forming a minority government in 2007, and upgrading to a majority in 2011. But what of their record in government?

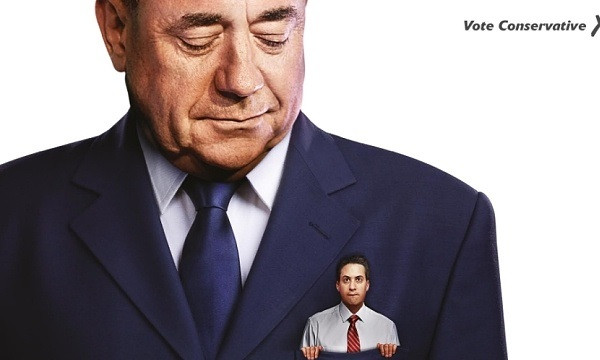

The SNP characterises itself as a left-wing anti-austerity party. In the 2015 Westminster elections, it all but wiped out Labour in Scotland after taking a tougher stance on public spending cuts than Ed Miliband's ill-fated shadow cabinet. Meanwhile, the Conservative campaign lumped the SNP and Labour in together, warning voters that Miliband would need a coalition with the Scots to secure Number 10, giving the hard-left the keys to Downing Street.

Or would it? For all its railing against Tory cuts and Labour's supposed acquiescence to the mantra of austerity, the SNP's own record in power, and its past policy platform, is hardly MacMaoism. "I think you've got to separate the party as part of a wider movement, and as a party of government," Dr Craig McAngus, a politics lecturer at the University of Aberdeen, told IBTimes UK.

The Scottish independence movement tends to be more left-wing than wider society. The vocality of independence activists and grassroots SNP members fuels a perception of the party as wholly on the centre-left. But, according to McAngus: "In overall terms, of ideology in an absolute sense, I think the SNP is quite a centrist, slightly left-leaning party with some liberal credentials."

Progressive or regressive?

Holyrood's powers under the devolution settlement are limited, but expanding, a consequence of Westminster's promises (or bribes, depending on your view) during the referendum campaign as it sought to convince Scottish voters not to break up the 300-year-old union.

The SNP has used its spending powers to keep university education free and abolish prescription charges. While it believes such services should be free to all on principle, critics argue these are regressive policies because they are expensive perks for middle and high earners. Essentially, taxes paid by low earners are used to fund free services for people wealthier than they are and who could pay their own way, such as through a graduate tax to fund higher education.

I think the SNP's quite a centrist, slightly left-leaning party with some liberal credentials.

The party has also frozen Scottish council tax for nine consecutive years, squeezing council budgets in what is effectively a tax break for the middle class at the expense of funding for local services, such as education. Not only that, but the SNP is decentralising some spending powers to put power in local people's hands. Or, a sceptic might argue, to pass the buck of difficult financial decision-making as Westminster cuts Scotland's central budget.

"By assigning a share of income tax to councils, they will be less reliant on central government funding, and incentivised to grow their local economies," says the SNP manifesto. Under plans unveiled by John Swinney, the SNP's deputy first minister, local councils will also set their own business rates, which are currently fixed by the centre — an attempt to drive them down by increasing competition between councils.

Moreover, the Labour party in Scotland is proposing a 1% income tax rise to offset the financial effects on local councils of funding cuts and the council tax freeze. As Owen Jones, the left-wing columnist, put it in the Guardian, cuts "become a choice".

But the SNP rejects this proposal, calling it "completely unacceptable and entirely regressive" because it is a tax rise across the board, though Labour argues increases to the personal allowance — the earnings threshold at which income tax begins — mean low earners would not be worse off.

Alex Salmond, leader of the SNP before the independence referendum, once pledged to reduce corporation tax below the rates of the rest of the UK, already low by European standards. They are so low, in fact, that Chancellor George Osborne has been accused of turning the UK into a modest tax haven. It was the SNP's desire to turn an independent Scotland into a hyper-competitive economy with lower corporation tax than the Thatcherite Conservatives south of Hadrian's Wall.

Talking a good game

As it is, the SNP must project itself as to the left of the Labour party to maintain its broad coalition of support from across the disaffected centre and left of the Scottish political spectrum. McAngus said this is easier to do in the context of Westminster than Holyrood because the SNP must be a party of government in Scotland.

"The SNP is in a position where it can almost see things, and do things, and present itself in a particular way because it will never have to implement it at least at the Westminster level," he said. "They can talk a good game, and say 'we're here to end austerity', and then actually be able to say 'we couldn't because the Labour party wouldn't let us', and it's a very easy get-out clause."

A benevolent Scottish nationalism which seeks self-governance is the glue binding the SNP. But as Scotland secures more power and control through devolution, the SNP's internal ideological contradictions may stretch to breaking point. How does an empowered governing party which contains the Bennite socialist MP Mhairi Black and pro-market MSP Fergus Ewing reconcile itself?

"I don't think the powers will produce any kind of radical change," Paul Cairney, professor of politics and public policy at the University of Stirling, told IBT. "One issue with them is I never think there's been a more confusing settlement. At the start, you could have a good idea of what they were responsible for. They had limited tax and social security powers. Now they've got all these shared powers and responsibilities for little bits of taxation... I think they've still got the ability to blame the lack of devolution for the things they do."

McAngus said when parties are electorally successful "people tend to shut up and just get on with it". But independence, the party's raison d'être, is where division may grow. "It will be probably over the timing of calling a second referendum, or the structure of the SNP's, the Scottish government's, argument for an independent Scotland the next time around," McAngus said. "Were the lessons learned from last time? Is the vision of an independent Scotland the SNP espousing radical enough?"

The SNP is pro-EU. If the UK votes to leave the EU on 23 June, it will almost certainly trigger a second independence referendum in Scotland, when voters would be likelier to back breaking free. "The SNP could split up because its main goal has been achieved," Cairney said. "I think before then, they still seem too professional for that sort of thing to happen."

Before the 2015 general election, Salmond's successor Nicola Sturgeon dropped the policy of a blanket cut to corporation tax. It was seen as symbolic. Does Sturgeon's ascension herald a more left-style of politics for the SNP? "I think they'll stay centrist," Cairney said. "They'll do centre-left things. I think they'll try, for example, and reintroduce this idea of universalism in the provision of public services. But I don't think it will go much further than that."

McAngus said there is still some time to go before Scotland knows what Sturgeon is ideologically about. "I think we haven't had enough time yet to really judge that as a first minister in government," he said. "I think the next five years will give us that opportunity."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.