Second language learning theories: Why is it hard for your adult brain to master another dialect?

The older we get, the more difficult it becomes to learn another language. Why? Some say our brains are only built for it when we are young. Some say it is the way we are taught that does not cater towards an adult learning pattern. Some even say that certain individuals may just not have the brain capacity for it.

Connections in the brain

Scientists at the Society for Neuroscience have been hard at work analysing why some people struggle more than others to pick up another language. They wrote in the Journal of Neuroscience that learning a second language depends on the strength of connections in the brain.

"The most interesting part of this finding is that the connectivity between the different areas was observed before learning," said Arturo Hernandez, neuroscientist at the University of Houston. "This shows that some individuals may have a particular neuronal activity pattern that may lend itself to better learning of a second language."

They found that stronger connections between the left anterior insula and the left superior temporal gyrus parts of the brain made individuals better at speaking the language. At the same time, connections between the left superior temporal gyrus and the visual word form area of the brain decide the competency of reading.

Teaching troubles?

Education experts from the language-learning app Voxy, suggest the problem lies more with the way that adults are taught to understand the new dialect. They think we try and learn as much vocabulary as possible – which can be stored with relative ease – but then ultimately do not know what to do with all of the information when we try to put it together.

Katie Nielson, chief education officer at Voxy, told Business Insider: "In history class, you start chronologically and you use dates in order of how things happened. That's just not how language-learning works. You can't memorize a bunch of words and rules and expect to speak the language. Then what you have is knowledge of 'language as object'. You can describe the language, but you can't use it."

Nielson uses the example of learning the past perfect tense - the tense used to described an action that had finished before another has started. She says that learning the different verb conjugations for the past perfect does not mean you can hold a conversation with someone who speaks that language. It simply means that you can use the past present correctly when you have to.

This is the difference between learning French as 'an object', for example, as opposed to French as 'a skill'.

Linguistic skill has nothing to do with learning a language

Are you a strong mathematician, but struggle with picking up a second language? Researchers say you could be in the small percentage group of people that experience this. They suggest that being linguistic is associated to picking up on patterns in maths, and non-verbal reasoning. The research from Hebrew University, and published in Psychological Science, used short 15 minute tests to discover the link.

That could explain why some people struggle to learn new dialects, as a study from Johns Hopkins University says that most people are born bad at maths.

"These new results suggest that learning a second language is determined to a large extent by an individual ability that is not at all linguistic," said Ram Frost, lead researcher of the study.

"This finding points to the possibility that a unified and universal principle of statistical learning can quantitatively explain a wide range of cognitive processes across domains, whether they are linguistic or non-linguistic."

It all comes back to your routes

Another study from Rutgers University, New Jersey, has suggested that different nationalities of learners experience different levels of difficulty in learning the same language. So, if you struggle to learn German for example, it may be because you are thinking about translation too literally.

The research, published in Studies in Second Language Acquisition, studied how an English student and a Romanian student differed in learning the Spanish for "yesterday the man ate", or as it translates "yesterday the man eats". As the English translation is slightly different, it was more difficult for the English student to pick up.

Nuria Sagarra, co-author of the study, told MedicalDaily: "If your native language is more similar to the foreign language (e.g. your native language has rich morphology and you are learning a different rich morphology, such as a Russian learning Spanish), things will be easier."

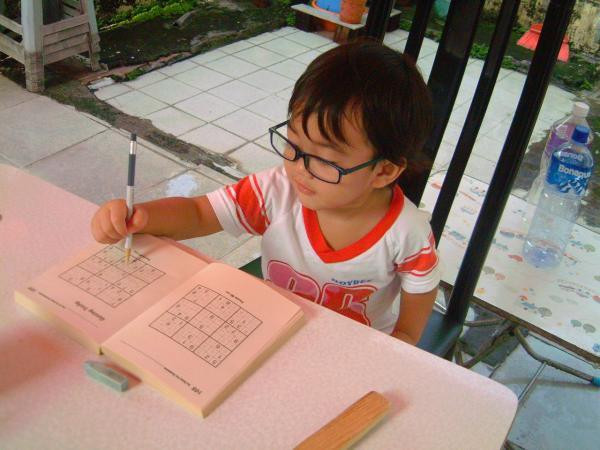

Baby brains put us to shame

Of course, the more commonly accepted theory is that the mind is catered for learning when we are young – not necessarily when we grow up. Scientific advisors at The Urban Child Institute say that a baby's brain has up to twice as many synapses (connections in the brain) than adults. This is a response to the trauma they have experienced in birth, and the brain overcompensates by creating as many connections as possible.

The young child will almost certainly not need to use that much space – like having a 128GB iPhone when you only use it to text your mum. With that added space, the brain can store as much information as it wants – most of which will indefinitely remain throughout later life, hence how we continue to understand our first language up until we pass away.

After the child turns around six-years-old that ability is lost and they are resigned to the aggravation of French or Spanish lessons like the rest of us.

William Alexander, writer for The New York Times and author of 'Flirting with French', summed this up by saying: "Adult language learners are, to borrow a phrase used by some psycholinguists, too smart for our own good."

The reality is that there is most likely no sole reason for adults struggling to learn a language. It is a combination of the above, and then some too.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.