Secrets of the Great Pyramid of Giza's hidden void could be revealed by these tiny flying robots

The mini robots have been designed to fit through a 1.5 inch-wide hole.

Ancient Egypt's secrets, hidden for centuries, may finally be revealed with the help of a pair of tiny, flying robots developed by French scientists.

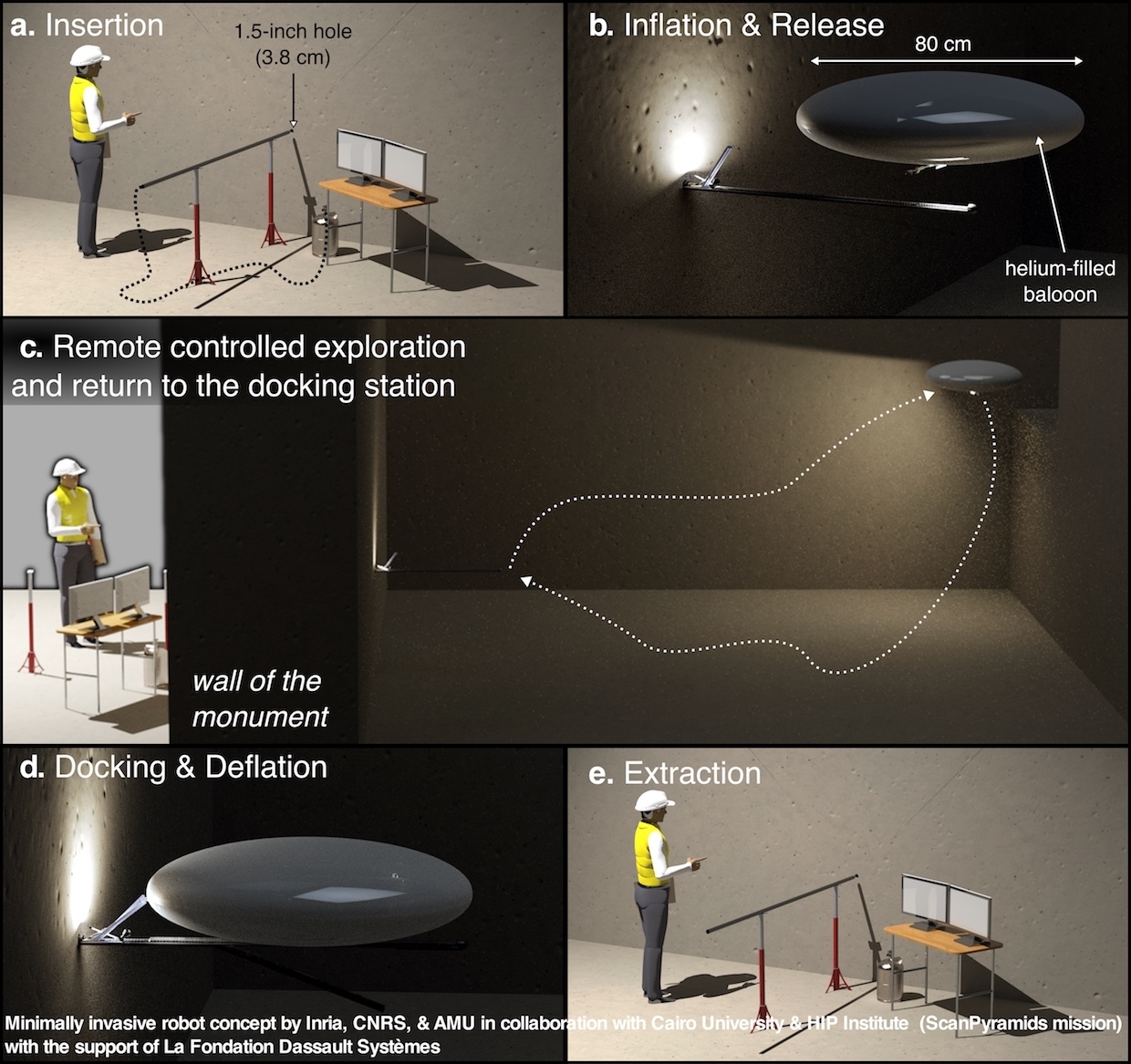

The two mini remote-controlled robots could reportedly help researchers peep into the giant hidden void that was recently discovered right in the heart of the Great Pyramid of Giza. The bots could also reach other inaccessible places within the ancient pyramid, without causing much damage to the structure, according to reports.

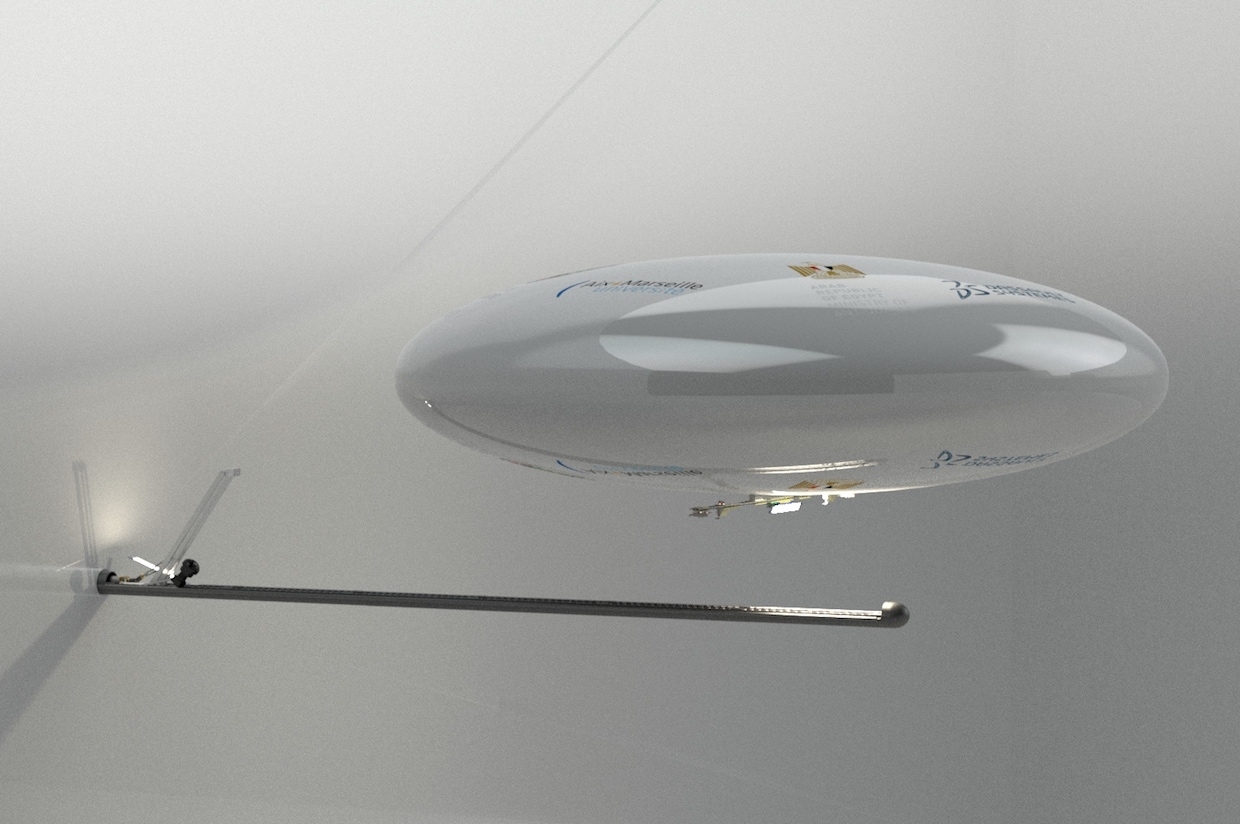

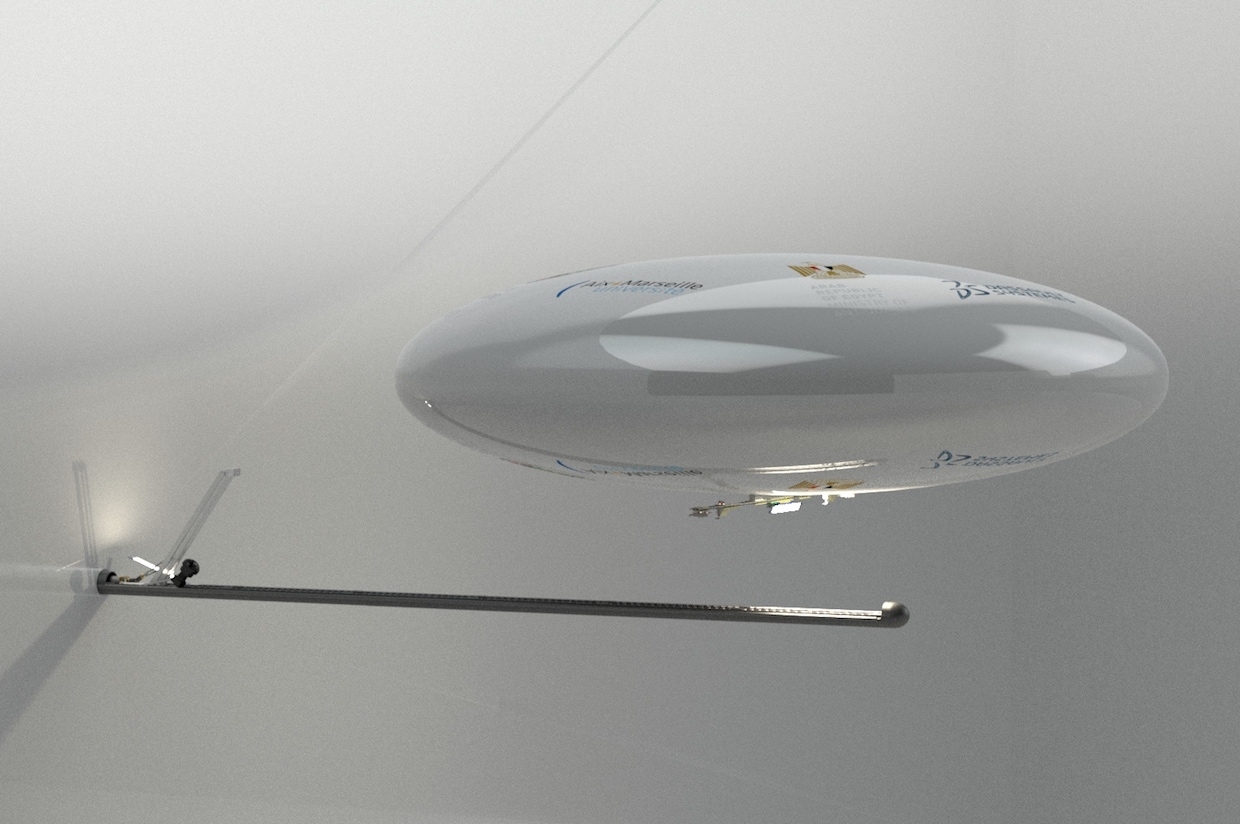

The two robots are built for two separate purposes. While one tube-like robot, fitted with an omnidirectional camera, is designed to take high-resolution photos of the mysterious void within the pyramid, the other robotic blimp has been designed to explore the area.

French robotics researchers at the CNRS and Inria research institutes, working in collaboration with the ScanPyramids project, now hope to drill tiny holes into the Giza pyramid, so as to not cause the ancient structure any damages.

Researchers hope that the robots, which have been designed to fit through a 1.5 inch-wide hole, can be shot through those miniscule holes. The exploration robot has been designed in such a way that it can shrink and be stuffed through a tiny hole, only to later inflate and explore once inside the pyramid. The floating robot also comes with a 50 gram payload, which includes cameras, lights, sensors and a navigation system.

One of the main challenges of this project is to ensure that the robots return from the Great Pyramid, even if it is damaged or loses contact with the operators.

"Unfortunately, tiny flying robot (blimps or quadcopters) cannot carry a tether because this would weight too much (even a light wire), add friction because of the part of the wire on the floor (and the small UAVs cannot pull much), and, overall significantly disturb the flight when we want to do more than hovering," Dr Jean-Baptiste Mouret, a senior researcher at Inria, who is leading the research team developing the robots, told IEEE Spectrum in a recent interview.

"This is why we are using the lightweight bio-mimetic sensors to design a 'virtual tether': the robot needs to be able to come back autonomously even if it loses the radio connection and it needs to dock more or less autonomously (so that we do not rely on expert piloting skills)."

According to Dr Mouret, these tiny robots may have applications beyond archaeology, including potentially conducting post-disaster inspections of areas affected by nuclear energy and more.

However, it may still be a while before the robots can be deployed within the pyramid.

"We recently joined the ScanPyramids team to think about the constraints implied by such a project and be ready if there is an opportunity. However, the ScanPyramids teams needs first to refine the positions of the voids (with more muon measurements) and we will, of course, need authorisation from Egyptian authorities before doing anything. For now, sending our robot in the Great Pyramid is still a dream: There is no concrete plan yet, and we might end deploying the robot in other places," Dr Mouret added.