Sixty years after Hungarian refugee crisis, how things have changed

Hungarians fleeing Soviet repression were welcomed by the West in 1956 - but Hungary has responded to the latest influx of refugees by sealing its southern border with razor-wire.

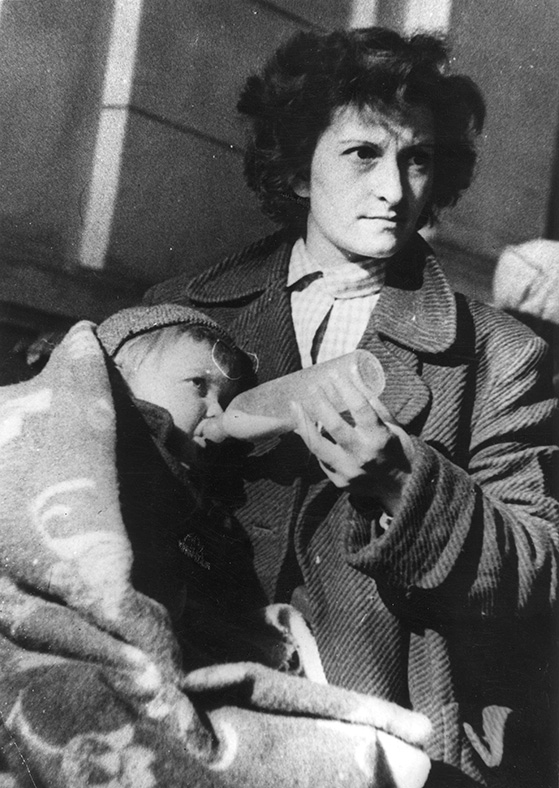

Sixty years ago, Soviet tanks crushed an anti-communist uprising in Budapest, sending 200,000 Hungarians – men women and children – fleeing across the border into Austrian refugee camps, then onwards into a welcoming Western world. They quickly found new homes, beneficiaries of the most efficient relocation campaign the world had ever seen.

Today, memories of that welcome brim with irony in a land that spurns a new generation of refugees fleeing fighting, abandoning their homes, as Hungarians themselves did before them. Present-day Hungary opposes a policy that would require all EU states to take in some of the hundreds of thousands of mainly Muslim migrants seeking asylum in the bloc after arriving last year.

The country's right-wing Prime Minister Viktor Orban has led resistance to the stance taken by German Chancellor Angela Merkel, who has said EU states have an obligation to share the burden of taking in refugees. He responded to the influx last year by sealing Hungary's southern borders with a razor-wire fence and deploying thousands of soldiers and police.

The government and some former refugees dismiss parallels between today's migrants and Hungarians fleeing across the East-West divide after Soviet troops crushed the bid by a reforming Budapest government to leave the Soviet Bloc defence alliance. "The Iron Curtain divided two inalienable parts of Europe," government spokesman Zoltan Kovacs said. "Any comparison to what's happening now, third-country migrants trying to enter the European Union is ... ignorance of history."

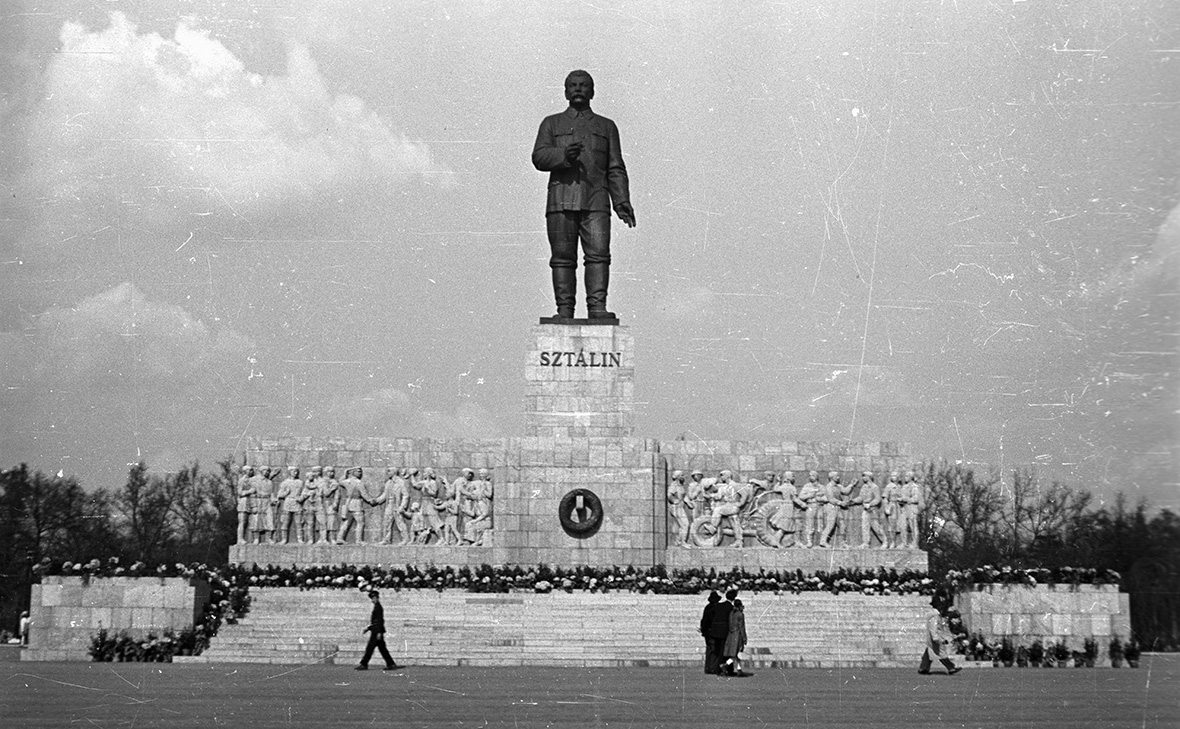

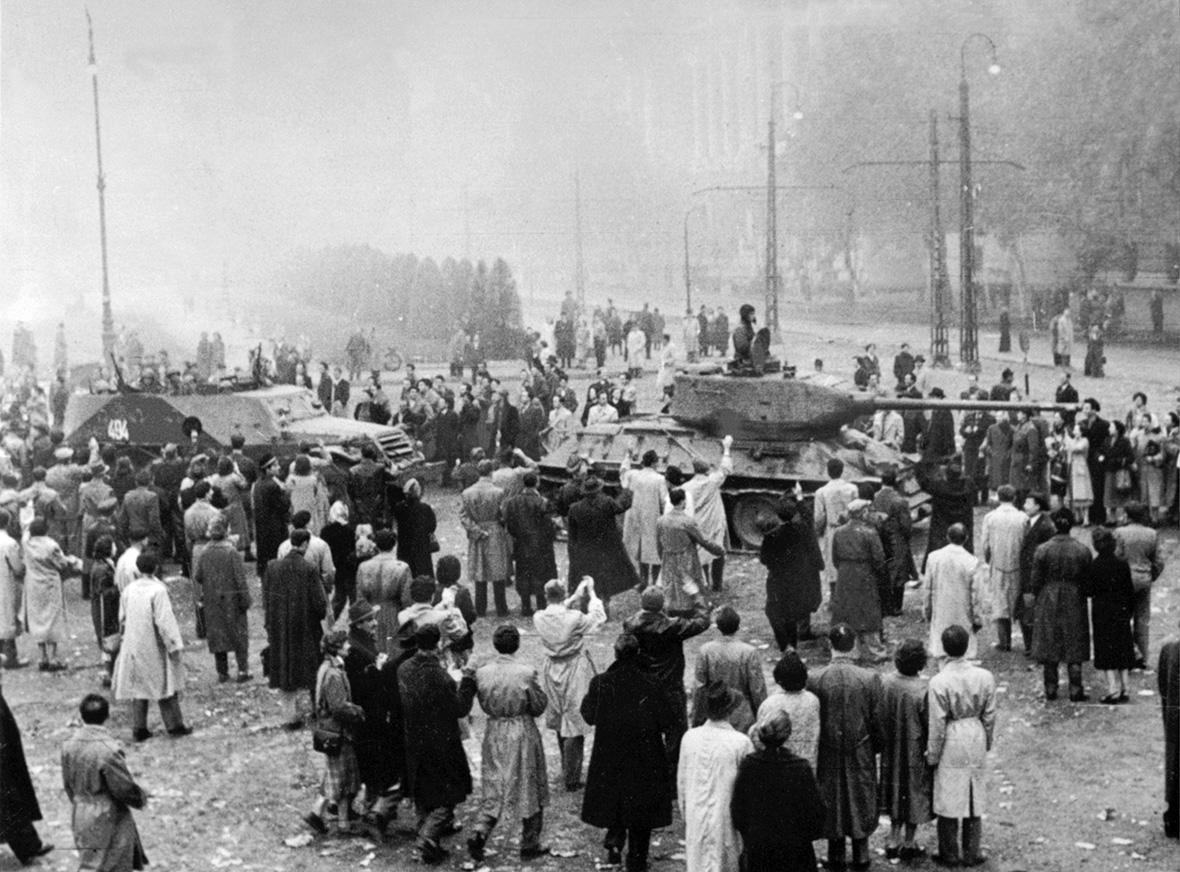

The 1956 uprising challenged post-World War Two Soviet domination of eastern Europe. The brief but bloody anti-communist uprising began on the afternoon of 23 October 1956 with a student march in Budapest in solidarity with reforms in Poland. By the evening, secret police had killed demonstrators who rushed the headquarters of Hungarian radio to have their list of 16 demands – including the withdrawal of Soviet troops – read on the air.

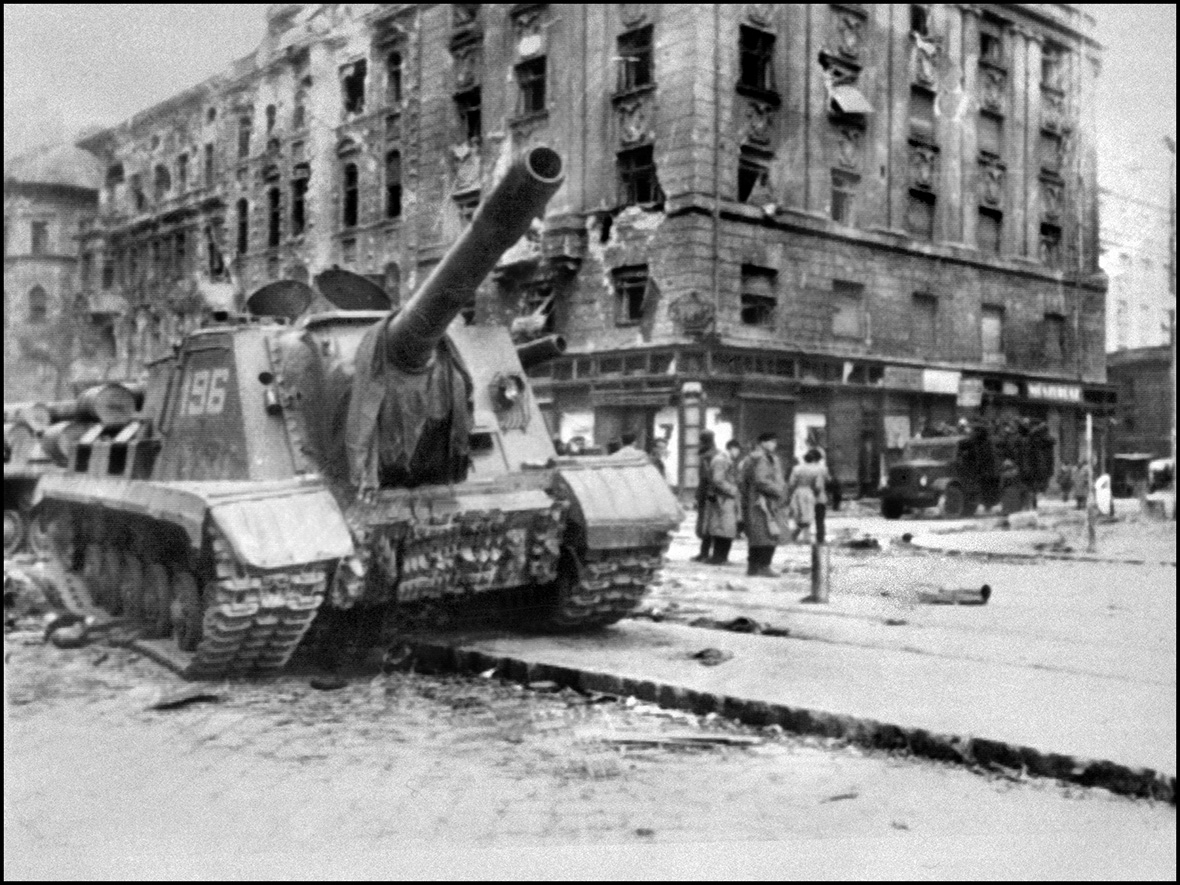

After days of street battles, Soviet troops withdrew on 30 October. The Red Army, however, returned on 4 November with more than 100,000 troops and as many as 4,500 tanks, effectively ending the revolution.

Over 2,500 Hungarians and 700 Soviet troops were killed and 200,000 Hungarian refugees fled the country, most toward Austria. Hundreds of revolutionaries, including Prime Minister Imre Nagy, were executed in the wake of the uprising and the establishment of a Soviet-backed government led by Janos Kadar.

Protesters disturbed the Hungarian government's commemorations of the 60th anniversary of the anti-Soviet revolution of 1956, as supporters of Orban tried to stifle them, sometimes violently. "We Hungarians have started on the more difficult road," Orban said. "We have chosen our own children instead of immigrants, work instead of speculation and aid, standing on our own feet instead of enslaving debts, and border defence instead of raised hands."

Orban also criticised the concept of a "United States of Europe," which would theoretically diminish the influence of individual countries. He likened EU bureaucrats in Brussels to the Soviet Union, a recurring theme in his speeches. "The freedom-loving peoples of Europe have the task of preventing the Sovietisation of Brussels," Orban said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.