Slavery Remembrance Day: Why fugitive terrorist John Brown was America's Greatest Emancipator

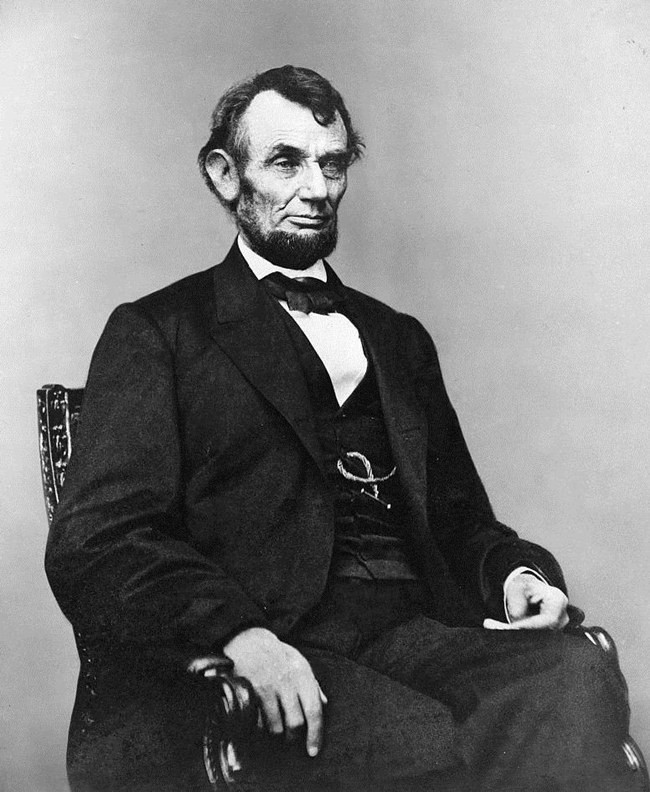

Today we remember Abraham Lincoln as the man who vanquished slavery in America. The man who achieved an impossible dream through the courage of his convictions, and ended up paying with his life. The man who created the multi-racial America that became a superpower.

This version of history is accurate, up to a point. Lincoln did deliver the Emancipation Proclamation, and he did direct the Union army to victory over the pro-slavery Confederates in America's Civil War. And he was killed in cold blood by a rabid opponent of abolitionism. These are all undisputed facts.

But, if you dig a little deeper, it's certainly possible to question the view of Lincoln we have today. He disliked the institution of slavery, but his commitment to abolition certainly wasn't unflinching; he wrote in the early stages of the Civil War that "If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it." Abolition wasn't the fundamental driving force of his life, more a political expedient harnessed to save the Union.

The real driving force of emancipation, the man who did more than anyone to banish the scourge of slavery, was a figure who has largely been airbrushed out of history, remembered only by keen students of the period. Whereas Lincoln's commitment to abolitionism was largely pragmatic, this man genuinely devoted his life to the cause, and it's possible Lincoln would never have risen to greatness without him.

John Brown was, to say the least, a charismatic figure. With his shock of hair, piercing eyes and booming voice, he would have attracted attention even without the bellicose passion which coarsed through his veins. A devoutly religious man, he fathered an impressive 20 children during his 59 years on earth, and like many other prominent Americans of this period (Ulysses S Grant among them), he was absolutely appalling with money, a failing which led to his applying for bankruptcy in the 1840s.

Yet Brown did have one very significant talent: rabble-rousing. He was a natural orator, and the force of his religious conviction, the belief that he was God's instrument, inspired others to fall in behind him. This skill enabled him to build a band of vigilantes in the 1850s and raise hell during the skirmishes in Kansas which provided a prelude to the eruption of the Civil War in 1861. To him, the end of abolition justified all means, no matter how barbaric; when his men surrounded a pro-slavery settlement in 1856, they slashed them to death with swords and left their bodies to rot.

These actions have caused many historians to dub Brown a terrorist, and even the man's greatest apologists must agree there is a grain of truth in this. But, just like Nelson Mandela a century later, Brown's violence had a higher purpose, and, like the great South African statesman, his extreme vigilantism played a key role in defeating the evil he so despised.

'He wasn't crazy, he wasn't a lone gunman in a cave'

According to Tony Horwitz, a historian who has written a book on Brown, "he had an extreme personality but wasn't crazy. That part of the stereotype, I believe, has gotten in the way of genuine understanding of this man and what he did.

"In some ways he was a conventional American of that era. He was largely self-taught, he was an American on the make, he fathered 20 children, he wasn't a fringe character in the outline of his life. He wasn't a lone gunman in a cave.

"His beliefs were that slavery was evil. He was descended from puritans and revolutionary war soldiers, classic New England stock, and he believed America's founding destiny of freedom and equality could only be fulfilled through the destruction of slavery. And he believed it was his God-given mission to do the job."

It is claimed that the kernel of abolitionism first entered Brown's mind when he saw a slave being beaten while travelling through Michigan. But he turned militant while he was in his 30s, when the slavery debate began to engulf the country, with William Lloyd Garrison publishing an incendiary pamphlet and abolitionist groups springing up all over the North.

"Brown wasn't a part of that movement but he began there, like many others," says Horwitz. "He gradually went his own way in a much more militant way.

"He didn't emerge quickly, he had business and family problems , [but] he spent decades plotting and planning and finally in the 1850s he became a public figure in Kansas, which is the first real battlefield of the civil war, the first time white northerners and white southerners were killing each other over slavery. He fought for the northern side, part of the militant wing of the anti-slavery fight. He became a national figure of that time."

Brown amassed a small guerrilla band, composed largely of his own family, and began raiding pro-slavery settlements. The most controversial foray came at a place called Pottowottamee in 1856. Horwitz takes up the story:

'In some ways he was a conventional American of that era. He was largely self-taught, he was an American on the make, he fathered 20 children, he wasn't a fringe character in the outline of his life. He wasn't a lone gunman in a cave.'

"He led a small band in the night in an attack on a settlement, dragged several men from their cabins and killed them in the night, shooting them and slashing them with their swords. It was a very brutal act that struck terror into the hearts of white southerners. The bodies were left where they fell."

The massacre was undeniably a callous act, which could easily have caused moderate abolitionists to turn against Brown. But the details of the massacre didn't really come out until later, by which time Brown had fought a pitched battle against pro-slavery forces at another place called Osowottamee, bravely repelling a much larger force of pro-slavery southerners.

Yet Brown was undeniably seen as a renegade in polite society, and he was driven underground, criss-crossing the Midwest and New England on a peripatetic journey, striking out at slavery settlements when the chance arose. In one of his night raids he freed a number of slaves and managed to ferry them a thousand miles, while being chased, before putting them on a boat to Canada.

This astonishing success pushed Brown's notoriety to new heights, and forced President James Buchanan to put a bounty of $250 on his head. Yet Brown was undaunted; he responded to Buchanan's bounty by offering $2.50 to anyone who could arrest the president.

Throughout this period, Brown's instinctive survival skills allowed him to hide largely in plain sight, says Horwitz.

"He was a skilled guerrilla, and he moved fairly freely in communities that were sympathetic to him. He would dine with prominent northerners such as [the writer Ralph Waldo] Emerson, he wasn't hiding in a cave. He would turn up from these exhausting marches and go straight to dinner with the great and the good of the northern states.

"He knew how to present himself as a warrior to these effete abolitionists. Some gave him money and guns. He was allied with Frederick Douglas, the most prominent black abolitionist of the day, and Harriet Tubman, the greatest woman involved in the underground railroad. So he had very prominent connections. He was not a lone gunman. He had a movement."

The final reckoning

The money which flowed from Brown's admirers was carefully squirreled away. Brown had been a lousy businessman in the 1830s and 1840s, but, when his calling came, he discovered a hitherto hidden shrewdness. He knew that he would need all the resources he could muster when the defining passage of his life arrived.

In fact that passage arrived quickly. In the summer of 1859 Brown hatched a plan to seize the Federal arsenal at Harper's Ferry, Virginia, and use the weapons to liberate a series of nearby slave settlements. The freed slaves would, in turn, allow him to wage a campaign of rolling liberation across the south, fanning out across the plantations and freeing their brethren as they passed.

The plan was ridiculous. Brown could never have beaten the entire US army, not to mention all those tooled-up plantation owners, by freeing a handful of slaves from bondage. But his religious faith brooked no argument; God had clearly mapped out this strategy, and who was he to quibble with the almighty?

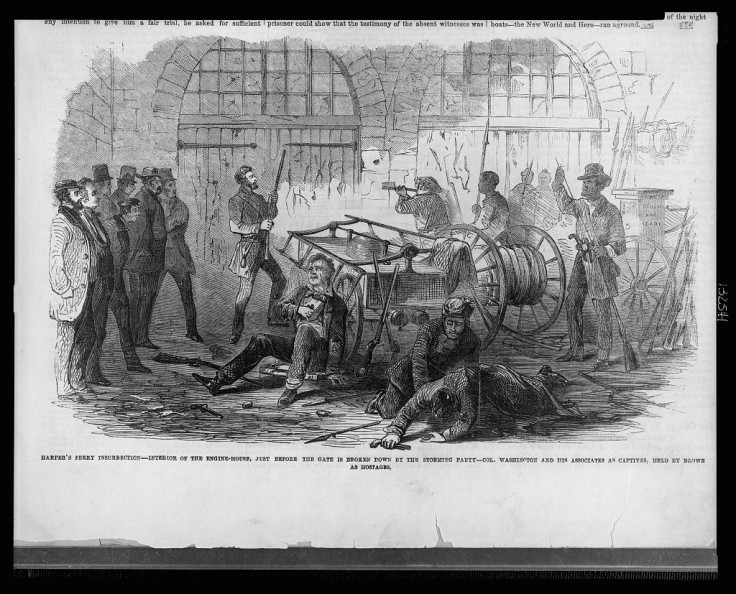

One night in mid-October he led a force of 19 men into Harper's Ferry, and succeeded in seizing the arsenal. But he only managed to free about 10 slaves from nearby plantations and was forced to hole up in the armoury, where he was surrounded a government force led by Robert E Lee – who ironically served as the Confederate commander in the Civil War, and went down in legend for the brilliance of his struggle against the Federal administration.

Brown was sure to hang. But, crucially, he was granted a trial, which allowed him to hammer the institution of slavery and push America into a turmoil from which war was inevitable.

"This is the great irony of Brown's story," says Horwitz. "He failed in his military mission, but he triumphed through the power of his oratory in court. His trial became a national sensation and he used it to really put the south and slavery on trial. He admitted to what he did, but insisted he was in the right because he was fighting this most evil of institutions.

"He made reference to the declaration of independence and the Bible, two documents that spoke powerfully to Americans, and said he was acting in accordance with them. He also wrote letters from prison and then, finally, went very gallantly to his death.

"He was surrounded by southern troops and thousands who hated him. He never flinched or gave any hint of fear or regret, and as a result he died a martyr to many in the north. He became almost a Christ-like figure."

Many of history's greatest figures have lived better than John Brown. But none has died better. In that courageous last stand, facing certain death, he achieved more than his raid on Harper's Ferry ever could have. He set America on an irreversible course towards emancipation, a course which killed thousands but ultimately freed millions.

Whenever we remember the victims of slavery, thoughts naturally turn to Lincoln. But he's already had plenty of credit; after all he's arguably the most famous statesman of all time, and surely the most venerated American. Perhaps we can switch the spotlight onto someone else for once, a person who really, really deserves it.

Thanks to Tony Horwitz for providing his insight on Brown's life. You can find links to Tony's books here.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.