South Sudan: High Hopes, Broken Dreams

When I arrived in Juba, South Sudan on 1 October 2012, the prospect of helping build a new nation seemed so exciting that it overcame any slight feelings of trepidation I might have had. I had worked in other African countries before, Kenya, Tanzania, Ghana; but this was different.

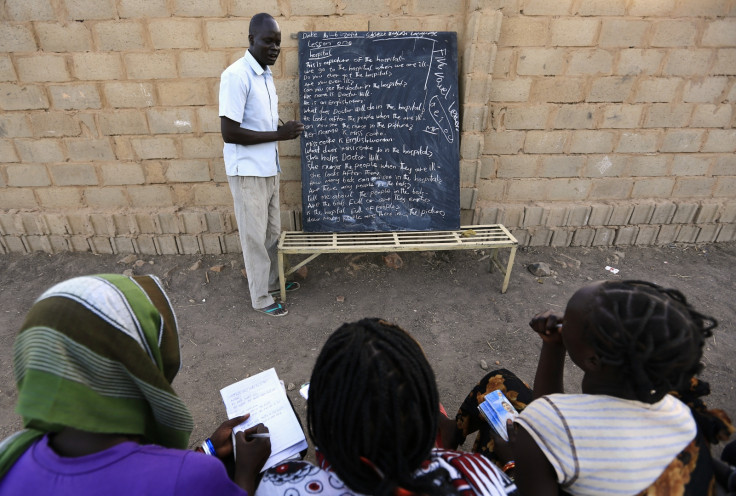

I had come to do a six month work placement with VSO (Voluntary Service Overseas) as their English language teaching adviser. The new Republic of South Sudan, which achieved independence from the north in July 2011, had recently declared English as the country's official working language as well as the language of instruction at all levels of education. My aim was to improve the skills of teachers, thus enabling them to deliver the new school curriculum through English.

There was huge optimism all round and Juba itself was bursting with energy. Well over a hundred NGOs were already operating in the country and many western governments, the US, UK, EU, Norway, Japan, were all investing heavily in developing the country's infrastructure.

Buildings were going up at breakneck speed. South Sudan had oil. The economic potential was huge. Little did I know, as the year drew to a close, that our enthusiastic plans and dreams were soon to be shattered.

15 December 2013 started out as a fairly normal day in Juba. I went to church as usual, which is what most people tend to do in South Sudan on a Sunday morning. I hurried back from church because, unusually, this particular Sunday was going to be a working day.

We had flown 12 of our tutors into Juba to attend our new 'master tutor' course and I had arranged to meet with them that Sunday afternoon. As the majority of teachers in South Sudanese primary schools are untrained, our work was crucial to South Sudan's development.

Our lively meeting broke up around five and everyone dispersed, looking forward to the course which was to commence the very next day. I went to bed early that night, exhausted, having worked non stop for seven days.

In spite of the heat, I slept heavily. I woke up to hear my phone ring a couple of times in the night but was too tired to get up and answer it. In the morning, I was startled to see several missed calls on my phone and umpteen text messages. 'Anna, stay calm'....'Seems there's fighting in the army barracks'...'It's not as bad as it sounds'...'Don't worry, it's a mere skirmish'...'Should be over soon'.

Apparently, there had been an attempted, thwarted, coup, but fighting had then broken out within the presidential guard. The fighting spread quickly to the other heavily armed army barracks around the city. Throughout the night, deafening gunfire had been lighting up the Juba skies, but I had heard nothing.

The conflict appeared to be mainly inter tribal. President Salva Kiir Mayardit (a Dinka) accused ex vice president Riek Machar (a Nuer) of plotting against him. Machar had been sacked from his post a few months earlier.

The Dinka and Nuer, who are the two most populous tribes and live side by side in the north of the country, have had a long history of rivalry, which was deviously stirred and fomented during the civil war by the government in Khartoum. In 1991 there had been a notorious massacre of more than 2,000 Dinka civilians in Bor, Jonglei state, carried out by Nuer fighters under the then command of Machar.

South Sudan Factbox:

Capital: Juba

Independence: 9 July 2011

President: Salva Kiir Mayardit

Population: 8,260,490 (disputed 2008 census)

GDP: $21.738bn (2014 estimate)

Juba was in meltdown. I realised, much to my disappointment, that the training course that we had all been looking forward to, was not going to start as planned that Monday morning. Thankfully, our neighbourhood was quiet, but an eerie silence descended over the city in between sporadic gunfire.

Juba returned to apparent normality by Wednesday but the fallout from those few days was huge. The killings spread quickly to the three northern states of Jonglei, Upper Nile and Unity which were populated mainly by Dinka and Nuer, and the three state capitals were soon brutally devastated by opposing forces.

Law and order had collapsed. Thousands died and thousands more fled their homes in terror. As of now, it seems that around 1.3 million people remain displaced inside South Sudan, afraid to return home, while an additional 451,000 have fled to neighbouring countries. Eighty-four schools remain occupied, either by armed forces or by displaced civilians.

I remained in South Sudan for another six months before returning to the UK. We kept hoping that the crisis would end and normality would resume. But the humanitarian crisis loomed larger and larger and donor agencies were diverting their funds to meet basic humanitarian needs. Development projects were no longer a priority.

Juba was in meltdown. I realised, much to my disappointment, that the training course that we had all been looking forward to, was not going to start as planned that Monday morning.

Back home in quiet North East London, I feel terribly sad for my South Sudanese colleagues who have no choice but to continue to live and work in a country that has become increasingly impoverished (in spite of the oil) and progressively insecure. The events of the past few months had put a stop to all our activities. The 'master tutor' course never happened, and many teachers in the country remain untrained.

After all the high hopes, nation building in the world's newest state seems to be at a standstill. There is a South Sudanese proverb which says: When two elephants fight, it is the grass that suffers. The poor grass in South Sudan has indeed suffered, terribly. I can only hope that it revives.

Anna Kulakiewicz is an education advisor at Windle Trust International, an NGO that provides access to education and training for those affected by conflict in Africa.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.