Srebrenica massacre: Meet the Belgian prosecutor who wants to jail Ratko Mladic and Radovan Karadzic

It was dawn on a hot May morning when Serbian Special Forces raided a house in Lazarevo, northern Serbia, and found Ratko Mladic about to take a walk in his yard. Pinning him to the ground, the soldiers ended a 15-year manhunt for one of the Balkans' most wanted men.

The so-called Butcher of Bosnia is blamed for the Srebrenica massacre, when 8,000 Muslim men and boys were murdered by Serbian military under his command at the height of the war in the former Yugoslavia, an event that has been classified as genocide by the United Nations.

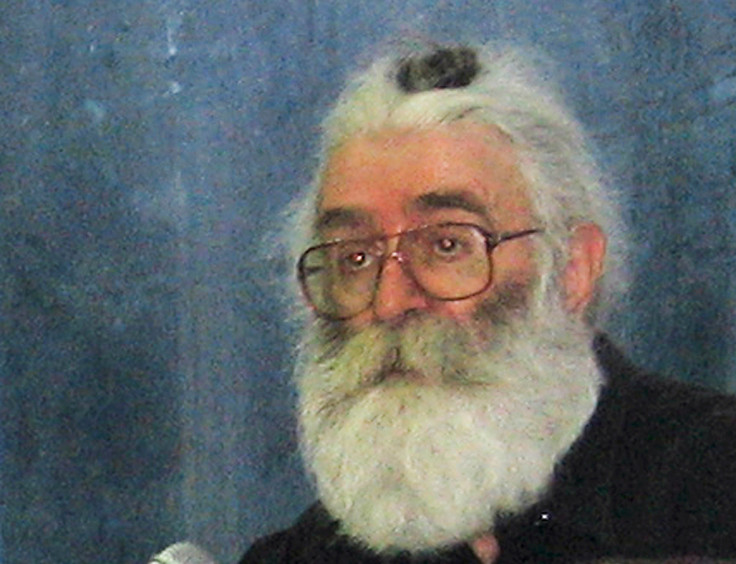

Serge Brammertz, a Belgian jurist and prosecutor for the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, remembers getting the call about Mladic's arrest. It came three years after Radovan Karadzic, the former president of Republika Srpska and the man alleged to have ordered Srebrenica, was also tracked down to a town in Belgrade.

"We are professional prosecutors and of course we leave our emotions out of the courtroom, but of course it was a great satisfaction in both cases when we got the phone call that the arrest operations were successful," Brammertz told IBTimes UK.

"In both cases, my first thought was the victims' organisations, and I was reminded of the many meetings we had with them. I knew that for a short moment it would give them a form of satisfaction, a recognition of what they went through."

When Brammertz took up the role at the ICTY, his first trip to Bosnia was to meet the families of those who died in July 1995, when Bosnian Serb soldiers killed more than 8,000 Bosnian Muslims – known as Bosniaks – in and around the Muslim town of Srebrenica.

At that time, many of the bodies of the victims were still missing (many remain so today) and Mladic and Karadzic were still on the run. Brammertz recalls the arrest of the two men – who are currently on trial for war crimes in the Netherlands – was a priority for the families.

"It was extremely important for the victims that those two key figures allegedly responsible for the crimes that were committed were brought to justice, and at all key moments of the trial many victims were present in the courtroom and following the proceedings," he said.

The families of victims of Srebrenica have long sought recognition from the authorities in both Serbia and Bosnia of what occurred on 11 July 1995 but in many instances, it has been lacking. Both Serbian and Bosnian Serb politicians have repeatedly denied genocide occurred at Srebrenica and in many parts of both countries, Mladic and Karadzic are considered heroes.

Indeed, both men had apparently been able to evade capture, live freely and in some cases even travel abroad both to work and watch football matches even as international warrants were out for their arrests. As for lower-level commanders that have been caught and jailed, many have been honoured when they are released.

"We have the situation where people who are convicted war criminals – even those who actually admitted responsibility for crimes – were received in their own community after serving their sentence as heroes, with all honours. That is one of the big challenges," Brammertz said.

"There is still a very fragile reconciliation process and this process can only be successful if people agree on the past. This is today absolutely not the case. In Bosnia alone depending on what you go school you have a totally different history book to teach students."

Given how divisive an issue the massacre and the war of the 1990s more generally remains in Bosnia, Brammertz said he is often asked whether he feels that work of the ICTY is beneficial.

While he feels that reconciliation in Bosnia has to come from within society, there can never be a hope of it unless figures such as Mladic and Karadzic are convicted.

"I fully understand that today there are many other challenges which are hitting the news every day, but the fact is that for survivors crimes committed 20 years ago are still at the centre of their lives today, every day," he said.

"Many family members still don't know where they are or what happened to them. The search for missing persons is still an important issue, thousands are missing and every year new graves are discovered."

There has been discussions in recent years about international justice more generally, especially given the fact that bodies such as the International Criminal Court have struggled to secure convictions and track down suspects.

The latest example of this is Omar al-Bashir, the Sudanese president accused of war crimes by the ICC, who was recently allowed to visit and then leave South Africa despite an international warrant for his arrest.

But Brammertz said that such criticism does not take into account the complexities of international justice. During Mladic and Karadzic's trials alone, the ICTY brought 400 witnesses to court. A more general challenge is tying leaders such as Karadzic, who was not at Srebrenica physically in July 1995, to the massacre there.

Genocide denial is still very common in parts of Bosnia and we are very far from a society that speaks with one voice

"I was a prosecutor in Belgium for 15 years and if an important crime was committed you had immediate access to the crime scene, you had all the experts you need, you had a clear legal framework and the support of both the public and politicians," he said.

"All this is absent in the international field. We have to conduct all our investigations abroad. Very often people we want are considered as heroes in their own communities. Often governments in place are in one way or another involved.

"We are talking about thousands of victims and thousands of perpetrators and everybody seems to know who they are. They are on TV or in leadership positions and we have to establish before an international court beyond any reasonable doubt that they are responsible. So it is a little unfair criticism, I think."

But while both Bosnia and arguably international justice has some way to go, Brammertz said the world that the ICTY operates in now is very different to a decade ago. The court previously had no dealings with the judicial authorities in Bosnia, Serbia or Croatia; now it shares information that has already seen lower-level historic crimes heard in local courts.

But 20 years after Srebrenica, there remains a wound in Bosnia that international justice alone cannot solve.

He added: "A lot still needs to be done. Every time an arrest takes place and it is of a well-known figure it gets complicated. Genocide denial is still very common in parts of Bosnia and we are very far from a society that speaks with one voice."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.