Stefan Stern: Britain's got talent and employers must realise the value of their workforces

You can't get the people. This has been the traditional cry of frustrated bosses who advertise vacancies but find to their disappointment that few suitable candidates apply to fill them. The UK's Office for National Statistics says that in May this year, there were as many as 734,000 vacancies in the British economy, a surprisingly high figure that reinforces the sense of recovery implied by an unemployment rate of 5.5%.

And yet, as I have mentioned here before, productivity remains disappointingly low, and prosperity is being enjoyed only by a small proportion of the country. In a speech on 30 June, Labour leadership candidate Liz Kendall said Britain has become "world class at creating low-paid jobs", and she has a point.

So perhaps several things are going wrong at the same time here: not only can we not "get the people", we aren't even designing and creating enough high value-adding, wealth-creating jobs in the first place.

Chuck in excessively strict visa and immigration requirements for those foreign workers who do have the right skills and your economy will be well and truly stuck: technically growing as activity returns, yet not getting much richer as the work being done is of too little value.

In this context, talk of "attracting and retaining talent" might sound a bit hollow. But "talent" has become one of those unavoidable business phrases that is bound to come up in management meetings again and again.

A new report from PA Consulting, The Future Is Fluid, takes another look at talent management and finds, disappointingly but perhaps unsurprisingly, that this question of developing people is still being mishandled.

The firm spoke to over 70 CEOs of large international businesses, two thirds of whom said talent management was one of their top five challenges. But less than half had a formal talent management programme in place. And under 5% had a system for collecting, storing and managing talent data.

Perhaps today's more uncertain and volatile trading conditions make talent spotting slightly harder to pull off. As Lesley Uren, a talent management expert at PA Consulting, says: "The war for talent has turned into a series of skirmishes around who can respond most nimbly." But some fundamentals about hiring and developing the right people have not changed.

High expectations from talented employees

Employers need to wise up in a number of ways. First, understand that the talented people they might want to hire are entering the jobs market with high expectations. As Michael Maccoby says in his new book, Strategic Intelligence, this new generation of workers "wants transparent and fully credible leaders who treat them as collaborators, not followers".

While pay matters, providing a stimulating and civilised work environment may matter more. In Rob Goffee and Gareth Jones's book, Clever, which is about working with talented staff, they quote an HR director who tells them: "I am a master of the dark [financial] arts of retention...

"Let me tell you, none of these will work if the competition really wants your people. On the contrary, they will only stay if you can offer them a great place in which to express their cleverness and other clever people to work with."

Flexibility and variety at work are important too. Goffee and Jones add: "The most effective clever organisations will be collections of 'value networks', or temporary value chains. These deliver a particular project or perform as a particular team and then, once they have completed their work, are reabsorbed in other places."

If this is the way the world has changed no wonder traditional "succession planning" has been found wanting in recent times. As PA Consulting's Uren says: "In many organisations, the roles listed on succession plans often will not exist in five years' time, while the people on these plans are often placed there without it even being clear whether they actually aspire to the role or not."

Employers should be growing their own talent: it's cheaper than hiring in and saves time on inductions, team-building, cultural awareness training and all the rest. So-called "stretch assignments", if chosen properly, can also help. Around half the CEOs interviewed by PA described being given a stretch challenge as a career-defining moment.

All employees – whether labelled as "talent" or not – notice pretty fast how their business is being run, and whether or not they should plan to stay there. This means the people stuff matters. HR should not be a joke but a leading player.

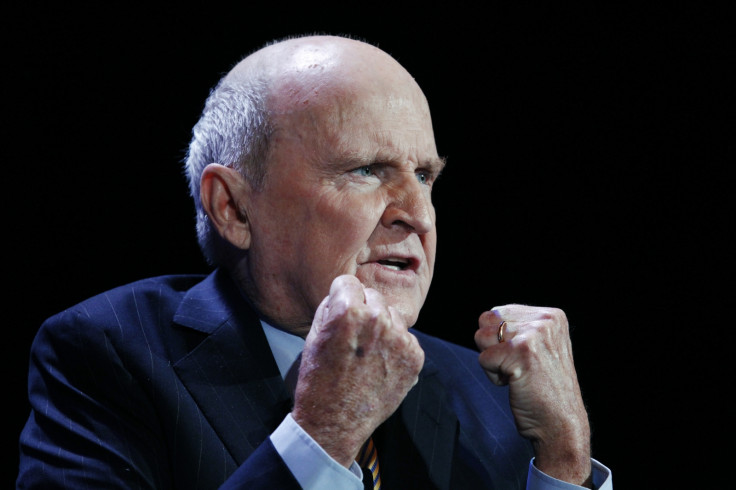

Jack Welch once said companies who think the chief financial officer is more important than the HR director are "nuts". But as Professor Ed Lawler from the University of Southern California wrote in his book, Talent: "The conclusion one has to reach based on this is that most boards are 'nuts', because they do, in fact, [usually] have their CFO present but not their head of HR."

Talent is mobile and on occasion impatient. If you want to attract it and then hang on to yours, you are going to have pay attention and make your talented people feel wanted.

Stefan Stern is a business, management and politics writer. He writes for The Guardian and The Financial Times and is a visiting professor at Cass Business School.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.