Stefan Stern: Leaders must break familiar thinking patterns to spot the next 9/11 or Bernie Madoff

How about this for a management innovation in 2015: being wise before the event? When something horrible and apparently unforeseen happens, such as the Charlie Hebdo murders, the hunt for missed warning signals begins. We rush to criticise security and intelligence officers, whose work will involve sifting through mountains of fragmentary and potentially misleading material.

Unless a true "surveillance state" is introduced – hardly a vote-winning proposal – not everybody can be watched all the time. And "hindsight bias", in any case, can lead us to conclude, erroneously, that something unexpected was in fact obviously going to happen.

Being wise before the event means analysing data intelligently. It means, above all, noticing things and acting on them. Max Bazerman, a professor at Harvard Business School, published The Power Of Noticing last year, a follow-up book to his earlier work, Predictable Surprises, which was co-authored by Michael Watkins.

Bazerman has been in London this week and he reminded his audience at an Institute for Government (IfG) talk on 12 January what had been known – but not properly noticed – in advance of the 9/11 attacks in 2001:

• The US government knew terrorists were willing to become martyrs for their cause and that their hatred toward the United States was increasing.

• In 1993, terrorists had bombed the World Trade Center.

• In 1994, terrorists had hijacked an Air France plane and made an aborted attempt to turn the plane into a missile aimed at the Eiffel Tower.

• Also in 1994, terrorists had attempted to simultaneously hijack 12 US commercial aeroplanes in Asia.

• Airline passengers knew how easy it was to board an aeroplane with items, such as small knives, that could be used as weapons.

Add all that up and it does indeed look as though "somebody should have noticed..." And some people did. Five years to the day before the 9/11 attacks, the US General Accounting Office, the investigative arm of Congress, published a report entitled Aviation Security: Urgent Issues Need To Be Addressed.

Learn to spot the missing information

Leaders need to notice things and act on them. That means not allowing your focus on a specific matter to prevent you from seeing what else is going on. "I want leaders to realise that 'what you see is not all there is' (WYSINATI) and to identify when and how to obtain the missing information," Bazerman writes.

At Harvard, Bazerman leads a Behavioural Insights Group, a multidisciplinary collection of academics who are trying to understand human behaviour better. But, ultimately, the goal for us all is to become what writer Saul Bellow called "a first-class noticer". Bazerman told the IfG event: "View it as your job to notice what's wrong."

This was a theme Warren Bennis, the leadership guru who died last year, was much taken with. Good noticers are keen to learn new things, he said. They are always developing. And they tend to cope better with crises and changed circumstances.

As Bennis wrote: "When those who lack adaptive capacity hit a rough patch, they tend to shut down and scar over. The fortunate remain hungry for experience no matter how severely they are tested."

Bazerman says good noticers are simply more perceptive: "They are less likely than most to be blinded by what they want the data to be, and more open to what the data actually suggest.

"A slew of recent crises occurred not because people misused information but because everyone, and most crucially the leaders charged with solving or preventing problems, missed often readily available information," Bazerman writes. He cites the following examples:

• Many people failed to notice that obvious data suggested it was too cold to safely launch the Challenger space shuttle.

• Many overlooked the fact that Enron's financial reports were fraudulent.

• Many did not recognise that Bernard Madoff's claimed investment returns were impossible.

• Many at Penn State University allegedly turned a blind eye to the abuse suffered by children under their watch.

• Few foresaw that the US housing market could trigger a global financial crisis.

"These crises can be explained," he says, "by the common failure of even very smart people to notice important information."

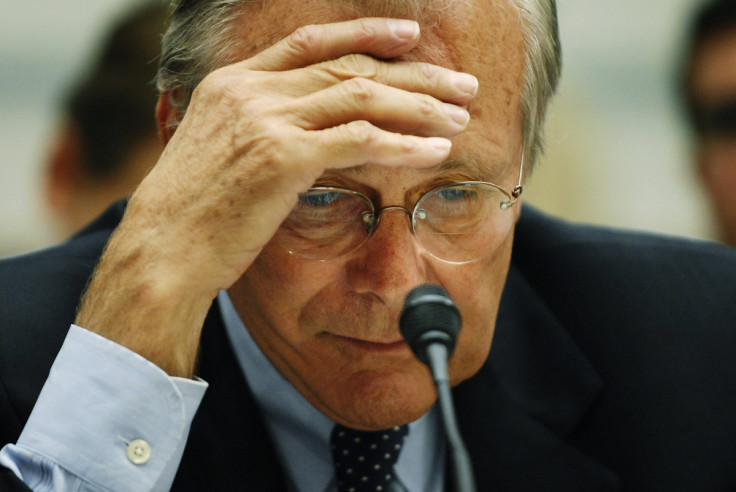

When Donald Rumsfeld gave us his list of "known knowns", "unknown unknowns" and so on, he left out arguably the most dangerous one: "unknown knowns" – things that somebody somewhere has seen but that nobody at the top of the organisation knows about.

Leaders have to try and ensure they get to see or hear about the things they need to know about, so that they can notice them and act upon them.

Stefan Stern is a business, management and politics writer. He writes for The Guardian and The Financial Times and is a visiting professor at Cass Business School.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.