Supernova Dust Factories Spurred Evolution of Early Galaxies

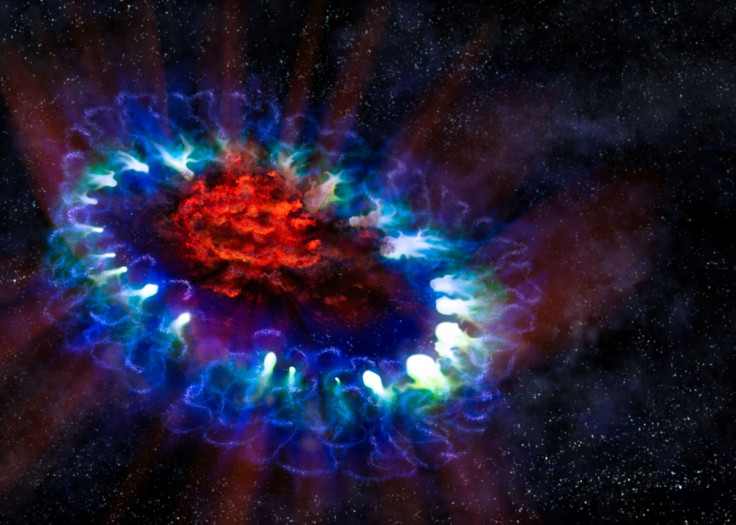

A supernova dust factory captured for the first time is helping astronomers understand the evolution of early galaxies.

Galaxies can be extremely dusty and supernovas – when a star explodes causing a huge burst of radiation – are thought to be the main cause of that dust, especially early on in the history of the universe.

However, evidence of how much dust a supernova can produce is lacking and does not account for the vast amount of dust seen in young distant galaxies.

For the first time, the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (Alma) telescope has captured the remains of a recent supernova full of dust that, if enough of it makes it into interstellar space, would explain how many galaxies came to have their dusty appearance and provide an insight into their evolution.

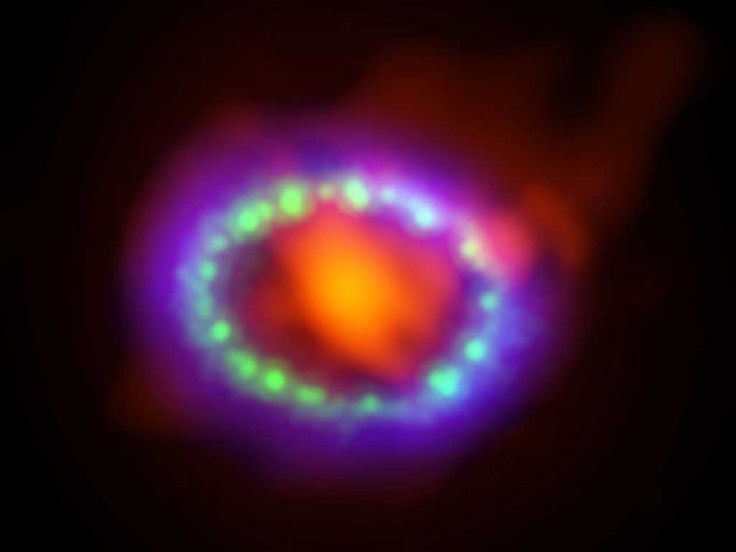

The international team of astronomers used Alma to observe the glowing remains of 1987A, in the Large Magellanic Cloud – a dwarf galaxy orbiting the Milky Way around 168,000 light years from Earth.

Light from the supernova first appeared to Earth in 1987, making it the closest observed supernova explosion since 1604 when Johannes Kepler observed a supernova inside the Milky Way.

Astronomers thought that as the gas from the explosion cooled, large amounts of dust would form as atoms of oxygen, carbon, and silicon bonded together. However, earlier observations showed only a small amount of hot dust.

Through Alma, astronomers were able to detect far more cold dust, estimating that 1987A contains about 25% the mass of our Sun in newly-formed dust.

Remy Indebetouw, an astronomer with the National Radio Astronomy Observatory and the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, said: "We have found a remarkably large dust mass concentrated in the central part of the ejecta from a relatively young and nearby supernova. This is the first time we've been able to really image where the dust has formed, which is important in understanding the evolution of galaxies.

"1987A is a special place since it hasn't mixed with the surrounding environment, so what we see there was made there. The new ALMA results, which are the first of their kind, reveal a supernova remnant chock full of material that simply did not exist a few decades ago."

The researchers note, however, that while supernovas can create dust, they can also destroy it.

Early observations of 1987a by the Hubble Telescope show that after being blasted out into space, some of the material hit an envelope of gas that sent it rebounding towards the centre of the supernova: "At some point, this rebound shockwave will slam into these billowing clumps of freshly minted dust," said Indebetouw.

"It's likely that some fraction of the dust will be blasted apart at that point. It's hard to predict exactly how much – maybe only a little, possible a half or two thirds," he said.

Explaining the significance of the images, Mikako Matsuura, of the University College London, added: "Really early galaxies are incredibly dusty and this dust plays a major role in the evolution of galaxies. Today we know dust can be created in several ways, but in the early Universe most of it must have come from supernovas. We finally have direct evidence to support that theory."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.