Texas attack: The chain of terror tweets that led to Elton Simpson rampage at Draw Mohammed contest

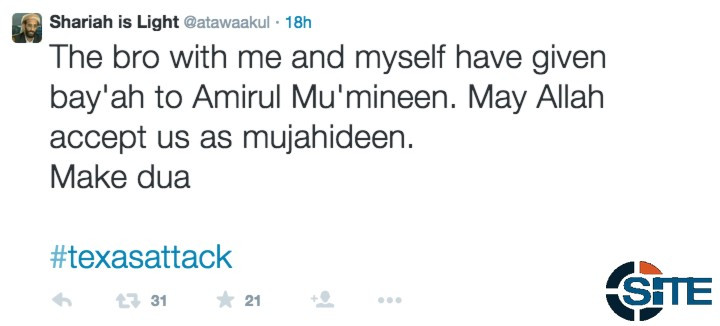

On 3 May, the Twitter account of "Shariah is Light"—later revealed to be an Arizona man and subject of terror investigations, Elton Simpson—hinted at responsibility for an upcoming terror attack in Garland, Texas and pledged allegiance to the Islamic State (IS) on behalf of himself and the other attacker.

This tweet and others like it, along with the actions they refer to, remind me of two questions people often ask me regarding some of SITE's reports.

The first: Who cares what some lunatic on a forum or social media says? The second: Isn't it beneficial to keep these messages online for intel?

The recent attack on the American Freedom Defense Initiative's "Muhammad Art Exhibit and Cartoon Contest" in Garland, Texas serves as a prime example for a case study to provide a clear answer: We should absolutely be concerned with one tweet, and no, we should definitely not keep them online.

Simpson's Twitter account and past show us the dangerous ingredients needed to bring an individual's call for violence to life: a community of like-minded radicals with virtually no deterrent to their communication; the mandate to act on one's beliefs; and direction to attack. All of these elements together, as may have been demonstrated by Simpson's actions, make a tweet much more than just a tweet.

Simpson on Twitter

The activity of Simpson's Twitter account was little different from other English-speaking IS supporters. It contained regular incitements for attack, retweets of new members' accounts after suspension, discussions with other jihadis, and IS messages. The user would even participate in the ongoing, tongue-in-cheek joke amongst jihadists about their love for Nutella, having once named his account "PButter or Nutella?"

His account also appeared to be embedded in the online IS community, an important aspect for those engaged in the group's movement. He followed more than 400 users, ranging from pro-IS supporters to hardcore IS fighters from around the world.

These accounts included alleged British IS fighters Abu Abdullah Britani (believed to be Abu Rahin Aziz, a radical Brit who skipped bail to be an IS fighter); Abu Hussain al-Britani (believed to be Junaid Hussain, an IS fighter linked to pro-IS cyber-attacks); alleged American IS fighter Abu Khalid Al-Amriki; an IS supporter from Australia, with the handle of Australi Witness, and various accounts of IS females. Important to note is that he was not only following these hardcore IS fighters and supporters, but that many of them were also following him.

Being a part of the IS network on Twitter, Simpson also adopted tactics used by IS supporters to avoid or quickly recover from account shut-downs. One such tactic used by him included changing handles and account names while keeping backup accounts prepared. Between mid- April and 3 May 2015, Simpson changed his handle and username at least three times:

Communication with Mujahid Miski

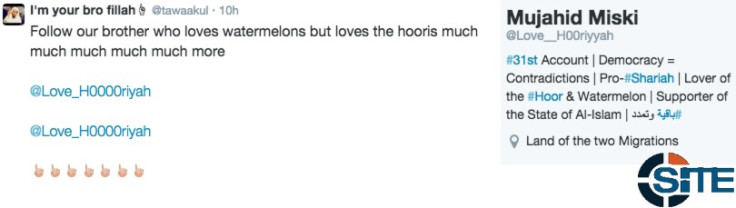

Among those that Simpson kept closest contact with on Twitter was "Mujahid Miski," believed to be Mohamed Abdullahi Hassan, a jihadist and IS-supporter from Minnesota believed to be fighting in Somalia. It is not clear if the two had known each other outside of the internet, but they shared regular conversations and appeared to have also spoken in secret discussions.

For instance, as Miski's accounts would regularly be suspended due to constant incitements for attacks against the West, Simpson would promote his friend's new accounts upon their creation. With one of his accounts, under the name "I'm your bro fillah," Simpson promoted Miski's 31st account:

Furthermore, upon Miski's establishment of this new account, Simpson was among the first that the former Minnesota man followed.

Response to Miski's Call for Attack?

On 23 April, Miski posted a link to an article on the upcoming cartoon contest by the American Freedom Defense Initiative, and urged for a lone wolf attack by "Brothers in the US" to the style of Charlie Hebdo:

Miski followed up by posting pictures of other lone wolf jihadist, including Paris attacker Amedy Coulibaly, and stated, "If only we had men like these brothers in the #States, our beloved Muhammad would not have been drawn."

The tweet was only retweeted nine times—a very small number for what would be considered by jihadis to be an important call for action (However, as I have always stated, it only takes one viewer to bring such threats to life).

Now, being a mutual follower of Miski on Twitter, Simpson must have seen the tweet calling for the attack in Texas. In this case, we know that Simpson not only saw the tweet, but that he also retweeted it:

Following the call for attack, Simpson, Miski, and other IS supporters would continue discussing and condemning US foreign policy in Syria, Iraq, and against Muslims.

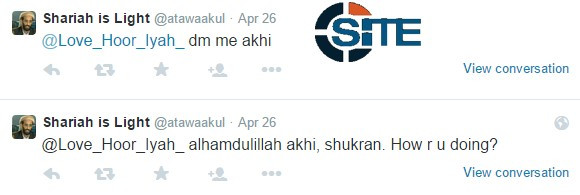

Notably, three days after Miski's aforementioned call for attack and Simpson's retweet of it, Simpson tweeted at Miski. The conversation, only parts of which are observable, showed Simpson greeting him and asking for Miski to direct message him:

While their conversation through direct messaging cannot be viewed, it is within reason to consider that the two may have been discussing Simpson's future attack. As we now know that Simpson had the intention to execute the attack, they had to keep any planning secret.

Afterward, Simpson's tweets would largely focus on "hoor," meaning the reward of women given to a martyr in Paradise. Though Simpson had discussed women of paradise before, his tweets on the subject increased toward the day of his attack. Between his (possible) discussion with Miski and his tweet implying responsibility for the 3 May attack, Simpson made 25 tweets regarding the women of paradise—something both Miski and Simpson had shared public discussions about.

On Sunday 3 May, Simpson made his final tweet, implying his claim and announcing his and his accomplice's pledge to IS. Abu Hussain Al Britani, one of the aforementioned prominent IS fighters following Simpson, would be the first IS fighter to forward the tweet. Both initiated the hashtag "texasattack."

Miski's Reaction to the Attack

Upon Simpson's final tweet and news of the attack being announced across media outlets, Miski celebrated Simpson as both a martyr and a friend. Amid these expressions, the user also suggested that he may have known about the attack before Simpson had committed it.

Miski tweeted more than two dozen messages, some of them very emotional:

Interestingly, in a conversation with another IS supporter, Miski wrote of Simpson:

Miski later explained what he meant: "He told me he was gonna send me a pic of him but Qadr Allah he didnt. I missed him by 12 minutes."

Miski also commented on Simpson's past desire to migrate to Somalia for jihad, stating: "Our brother Mutawakil in 2008 wanted to Make #Hijrah to Somalia but a Murtad [apostate] spied on him. Allah swt was preparing him for something better."

For many hours, Miski continued tweeting and discussing the attack, while expressing strong feeling towards Simpson, tweeting: "I m gonna miss how he always used to speak ..."; "I'm gonna miss Mutawakil, He was truly a man of wisdom"; "I'm gonna miss his greeting every morning on tiwtter [sic]." He also translated Simpson's pledge and implication of credit into Arabic, perhaps out of a sense of partnership in the attack.

It is possible that Miski's reaction was a result of an unpredicted death of his friend. Note that Simpson's final post didn't directly indicate an intended suicide operation. He wrote, "May Allah accept us as mujahideen." In the jihadi community, those looking to do suicide missions would more normally ask to be accepted "as Shuhadaa," meaning "martyrs." At face, asking to be accepted as mujahideen only means to be accepted as soldiers of jihad.

Two days after the shooting in Texas, IS claimed credit for the attack in its 5 May al-Bayan news bulletin. The statement identified Simpson and his accomplice as "two soldiers form the soldiers of the Caliphate [sic]."

The Power of a Tweet

The attack ended with a non-life-threatening injury to an officer—a relatively happy ending compared to other gun-related terrorist attacks in recent years. Still, the action in itself is alarming, and shows the power that a single tweet can exert when made inside a community like that of IS on Twitter.

So, let's revisit the two questions: Who cares what some lunatic on a forum or social media says? And the other: Isn't it beneficial to keep these messages online for intel?

Leaving accounts like Miski's active on social media for the sake of acquiring intel is like leaving landmines in a public field to study their placement.

These questions are often masked statements, and dangerous ones at that. They imply that calls such as Miski's are not actually threats and do not give way to dangerous actions, or that people's constant exposure to these dangerous calls for action are inevitable results of a scary new normal. They imply that people's lives are potentially worth gains in information.

Lone wolf attacks in recent years have answered these questions for us, and it's time to move on to other, more constructive ones. Maybe we could start here: How do we get these incitements and those expressing them off social media? Suspending accounts hasn't done anything to stop IS on Twitter.

Miski was on his 31st account when he made his call for violence in Garland, and on his 32nd when he eulogised Simpson. Furthermore, there are more users just like Miski, chatting with users just like Simpson—using Twitter and other platforms as virtually undisturbed venues to plot, coordinate, recruit, and inspire violence.

Leaving accounts like Miski's active on social media for the sake of acquiring intel is like leaving landmines in a public field to study their placement. While we are able to study recruitment methods, identify targets, and even gather information on future plans for terrorist groups, we are also endangering innocent civilians and facilitating the coordination and recruitment of people all around the world.

I understand very well that studying/monitoring terrorism and preventing it are two interconnected things, but the resulting lone wolf attacks and runaway teenagers are enough to prove that the costs outweigh the benefits.

Rita Katz is executive director of the SITE intelligence group (www.siteintelgroup.com). She has been monitoring terrorist activity and Jihad for more than a decade.

You can find her on Twitter @rita_katz.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.