Those calling for bigger flood defences don't understand the complexity of UK flooding

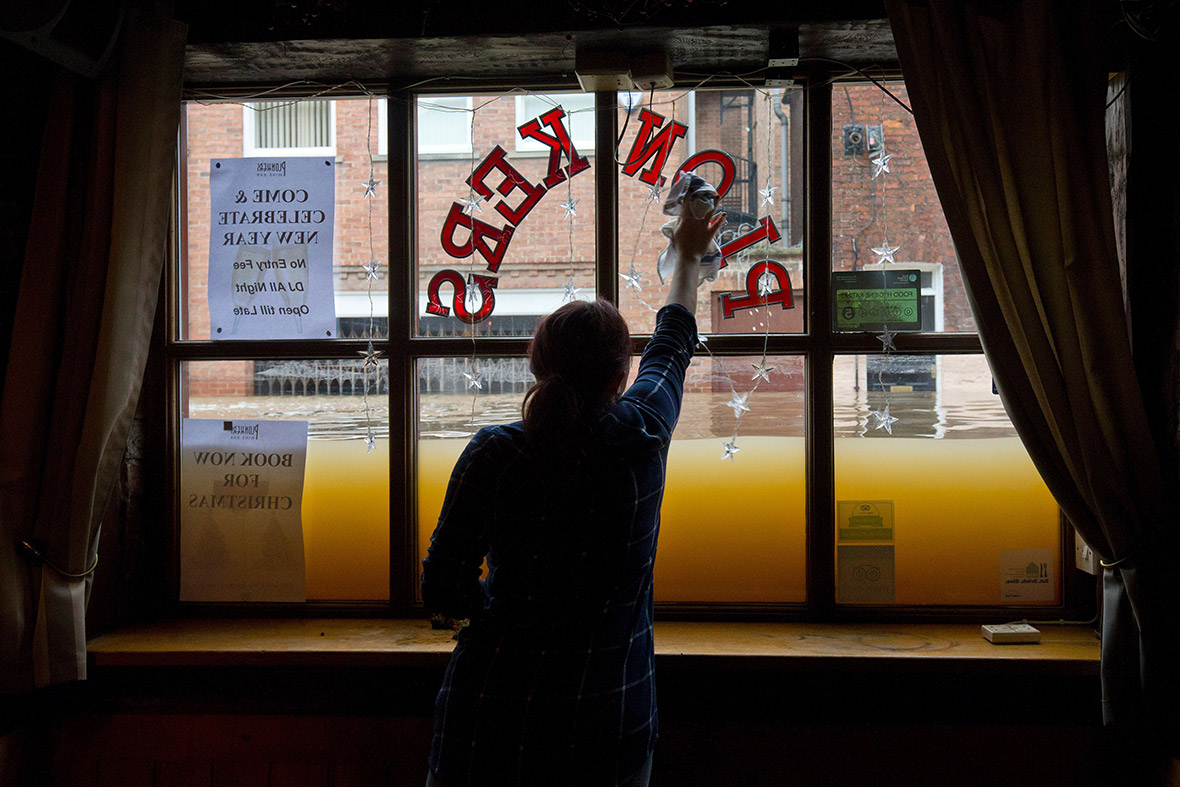

We've seen some pretty extreme rainfall recently in the UK, and as a result the flooding problem is spreading. Hundreds have been evacuated from their homes, and spiralling estimates of the flood damages are already projected at over £1.5bn.

The deluge has spread from the Lake District, badly hit during Storm Desmond, to Lancashire and Yorkshire during Storm Eva. The impact has been felt widely across Wales, northern England and parts of Scotland. Shap in the Lake District measured 65% of its usual annual rainfall in December alone. Likewise, Capel Curig in north-west Wales had just under 60% of their annual rainfall in December.

Storm Frank is also looming on the horizon. The Met Office have issued 51 flood warnings for England and Wales, nine of which are severe.

There are a number of disturbing tones to discussions in the wake of the devastating impacts on communities and people. The first of these is that defences have failed; the second is a debate over expectations in terms of the recurrence of these extreme floods; and the third is 'what should we do about it?'

These debates, as ever, are being conducted in emotive times while we have houses underwater and people displaced. While it is precisely these emotions that we need to encourage proper flood management - we need to make sure it's a constructive and integrated solution to flooding in the UK.

This is not a time to be reducing Government spending on flood management, particularly given the need for informed decisions over how and where to improve defences and how to manage our catchments and floodplains more effectively, both of which are expensive.

Obviously there is a need to deal with the immediate problem, but getting flood management right will take time and money – and money invested over the longer term in a considered manner not as a knee-jerk response.

The flood defences have not failed

Visiting the Environment Agency website you can see river after river exceeded all-time record levels across these December events. The Ouse (York), Eden (Carlisle), and Lune (Lancaster) burst their banks, and the list keeps growing.

Many new and expensive flood prevention or mitigation schemes did not fail in Carlisle, Kendall, Lancaster, Cockermouth and other places – they worked to capacity and were then simply overwhelmed.

Even in York, submerged by the Ouse and Foss, where there are tones of a blame game emerging, the situation appears to have arisen unavoidably because a pumping station was overwhelmed and a decision had to be made over opening flood gates, motivated by safety.

Get ready for more extreme floods

Many worry that these flood events are becoming more extreme and more frequent. After Storm Desmond there was a worrying misconception that 'this is a flood that should only happen every 100 years'. This is incorrect; the science of flood extremes uses the woefully short records of river flow (extending back ~40 years) and rainfall (~200 years) to estimate the chance of a flood of a given size happening.

A 100-year flood is actually better described as a flood that has a 1% chance of occurring within any given year. It does not mean that we expect only one every 100 years. Sadly these 1% chance events can occur more than once in 100 years, and quite possibly within the same year.

It is clear that we need better understanding of these extreme events. Given the short monitored periods for river flow and rainfall, we need to use all available data (including sedimentary palaeoflood data) to better define flood return frequency and magnitude.

As a geomorphologist, part of a group of scientists that study the processes and landforms of the Earth's surface, we have these longer time-scale data from the sediments of our lakes and rivers. From Bassenthwaite Lake the sediment record shows that three of the very largest floods experienced in Cumbria over the last 600 years have happened in the past 15 years.

This poses a key question: are these extreme floods becoming more frequent?

What we should do about it?

The real issue for society is what can or should we do to improve our resilience to these events. Already we see calls for investment in flood defence, and it is needed, but raising the magnitude of flood that our defences are engineered for comes at a price and is only part of the solution.

What tends to be forgotten is that we need parallel changes to our river catchments. Change to land management is needed to slow the flows and to reduce or spread the flood peak. This involves retaining water for longer in our uplands, on our slopes and floodplains, and requires more wetlands, trees, and less efficient run off.

In addition, there needs to be a serious look at the planning process to avoid floodplain development with these greater flood extremes firmly in mind. Changes to building and renovation practices might also help to render properties more resilient to events like this.

That said, the kind of extreme rainfall experienced this winter will always inundate floodplains. Hopefully the events of December 2015 will act as a catalyst for change that results in better landscapes for our environment and more connected approaches to flood risk management – not just bigger flood defences.

Richard Chiverrell is Professor in Physical Geography at the University of Liverpool, who currently researches catchment processes and palaeoflood records in the lakes of north-west England.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.