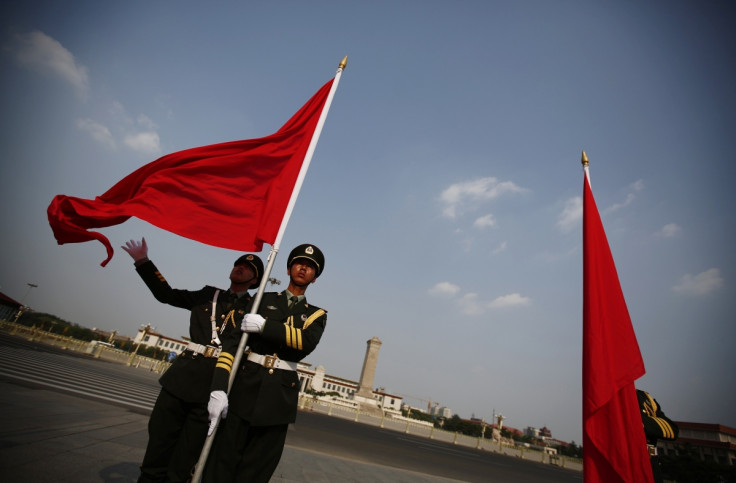

Tiananmen Square 25th Anniversary: Can Prosperity and Xi Jinping Reforms Prevent 'China Spring'?

A quarter of a century on from the Tiananmen Square massacre, everything and nothing has changed in China.

When the students took to the square in demonstrations that spread across the vast Asian state before they were murderously quelled by the authorities, the angry youth-led movement was demanding a democratic and prosperous future.

China is scarcely more democratic now than it was on 4 June, 1989. But it is increasingly prosperous. The world's second largest economy and soon to be the biggest, China is seeing rapid growth in wealth and incomes.

There has been a proliferation of billionaires and the West looks lustfully at their bulging wallets. Even the agricultural poor are gradually being lifted out of poverty as the magnet of urbanisation pulls them in to sprawling cities.

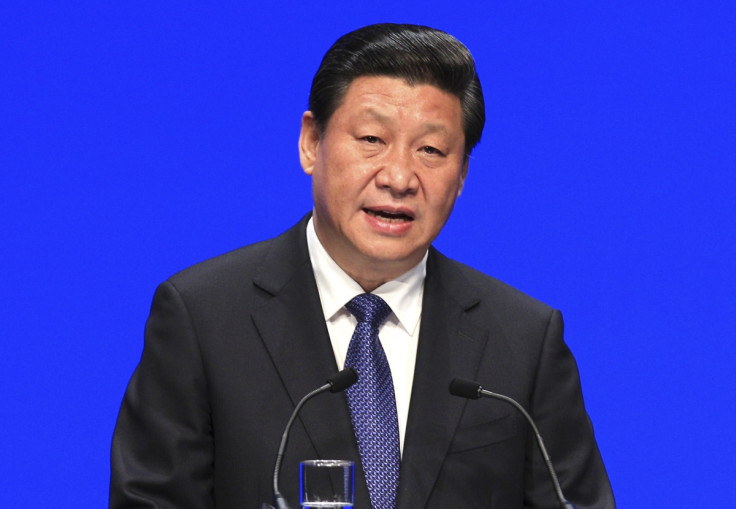

And to show the masses that the Communist Party of China is committed to change, President Xi Jinping unveiled sweeping reforms to the Chinese economic, financial and social system.

Yet there is still much dissent. The Chinese secret police and security services have managed to keep a lid on this boiling soup of discontent.

It occasionally spills out in the provinces with protests and acts of civil disobedience, sometimes against the endemic local corruption in China's bloated bureaucracy, sometimes over ethnic tensions.

These fractured, localised disputes have not yet morphed into a national movement. On Weibo, China's answer to Facebook and Twitter, grumbling and criticism is allowed about such issues. But state censors stand sentry, deleting any posts that attempt to arrange protest meetings.

As China embraces greater trade and financial ties with the West; as the pistons of industrialisation thunder on; as the political elite promise reforms – is all this enough to prevent another Tiananmen?

China's reaction to the 25<sup>th anniversary of the massacre – an event not officially recognised – suggests the authorities are still fearful of the power of the protestors' message.

"As in previous years, they rounded up activists and lawyers. What surprised us is how soon they started this time and the incredible scope and depth of the people they have been cracking down on," William Nees, a Hong Kong-based China researcher for human rights organisation Amnesty International, tells IBTimes UK.

"What we are seeing really is one of the largest crackdowns, certainly Tiananmen-related crackdowns, in recent years."

China's leadership faces a troubling paradox. To justify itself, the system and those who control it need increasing economic prosperity for the masses. But the better off Chinese people become, the greater the political and social freedom they will demand.

Jinping reforms

There was a big announcement at the conclusion of a four-day conclave of the ruling Communist Party's leaders in November 2013. An agenda for reform in China was unveiled.

Bringing China into the twenty-first century is a focus of Jinping, who took office in Mach 2013. He has promised "market forces" will be central to China's future.

Under the reforms Jinping will steward, China will scythe through its tangling red tape, make it easier for foreign firms to invest, loosen the rules around its one child policy, abolish the labour camp system, and crack down on the rotting influence of corruption, among many other measures.

Work is already underway to liberalise the tightly-controlled Chinese yuan, also known as renminbi, with London vying to become the currency's Western hub for trading.

And Jinping is leading a vast crackdown on corruption in business, with a number of high-profile graft investigations, the most well-known of which surrounding British pharmaceuticals giant GlaxoSmithKline.

"These reforms were necessary and something that we've been hoping to happen for some time," Dr Reza Hasmath, a China expert at the University of Oxford, tells IBTimes UK.

"The issue at hand here is that China's growth rate is actually decreasing and reforms were something that had to be accomplished."

Growth in the first quarter of 2014 slowed to 7.4% compared with 7.7% in the previous three months. And this is far slower than the 8.8% annual GDP growth reported in the same quarter a year before.

The government is consciously trying to stabilise Chinese economic growth from its current unsustainably rapid pace, which relies heavily on fiscal stimulus in areas such as infrastructure.

"Usually there is a correlation between growth and discontent. And so when growth decreases we see a rise in discontent," says Hasmath.

"The way you measure discontent is you see protests or grumblings on social media and so forth. The party is acutely aware of this and so that's why they actually need to have other forms of growth."

The regime wants a better-educated, urbanised population with an economy built more on service sector foundations. Its reforms programme will help this happen, but there is a risk to political stability from the resulting inequality.

"What you're going to find here is greater haves and have nots," Hasmath says.

"And that's where the discontent is going to occur. The have nots are going to be in the rural areas. They're the ones the party needs to be quite aware of. Ironically enough, that's where the party's greater base has been from."

Minzhu

There has already been a remarkable increase in disposable income for the Chinese after years of its growing trade with the rest of the world.

The country's National Bureau of Statistics says it grew from 10,493 yuan ($1,734, £1,045, €1,270) in 2006 to 24,565 in 2012. That is a 134% leap. And the Hurun Rich List said there were 314 dollar billionaires, up from none in 2013.

If the latest reforms come off, they should further improve the lives of many Chinese citizens, who will become wealthier and more economically free.

But there is noticeably little said in the reforms about arguably the single most-important freedom, minzhu – or democracy.

China is still now, and will remain as, a one-party authoritarian state that allows little freedom of expression and political dissent against the Communist Party hegemony.

"They're hoping that their economic reforms will give them the prosperity needed to hold off political criticism. It's kind of worked so far. It's worked to an extent over the last 25 years, but most economists tend to agree that we'll see lower rates of economic growth," says Amnesty's Nees.

"At the same time, a lot of the middle class – especially the upper-middle class – will be able to go abroad where you can of course access all sorts of free information, so the controls on ideology will be a lot less effective in future.

"And I think a lot of people who have perhaps had much more basic demands in terms of being able to have a decent job and be able to eat – the demands you might associate with dire poverty – once those are more or less alleviated and addressed then people will start to deal with a more higher-level demand.

"So there's fairness, and justice, and being able to practice their religious faiths without interference. I think these are different demands that are much harder for the government to address using their traditional toolbox."

Tibet and Xinjiang

For the majority ethnic Hans, a healthy economy trumps political rights. So if the ruling party can keep the Asian powerhouse's engine running, it will likely drown out the threat to its governance by pro-democracy and human rights campaigners.

But other ethnic groups, namely the Uighurs in Xinjiang province and the Tibetans, have not fared as well economically as the Hans. These tensions, building over time, are now exploding and are a concerning risk to the communists' rule.

In one extreme example, around 200 people died in ethnic clashes in 2009 on the streets of Urumqi, Xianjing. They were ostensibly protesting against central government repression of Uighur religious and culture, but there is more than this fuelling the unrest.

"Ultimately, what you're finding here is that the Uighurs and Tibetans are not doing as well as Hans are. And so they are turning to religion, to greater ethnic consciousness, and that kind of thing has flashed up in violence across these areas," the University of Oxford's Hasmath says.

"There's religious repression of course, but these things are spurred on more by socio-economic reasons. The party realises this."

The government is targeting economic support into these flashpoints in the hope that financial medicine will cure the social ills and so soften the political threat from different ethnic groups.

"They're hoping and they're praying that you can actually target those ethnic groups who are not doing well, because that's one of the major reasons for uncertainty," Hasmath says.

Every so often, Chinese rulers will lift the lid off of the pot to stop it from boiling over. These little releases of pressure seem to be enough each time, but the fire keeping the pot hot still burns in the longer-term.

It will only take one lapse in attention for the pot to boil over. Unless they turn the heat down with democratic reforms alongside the country's economic transformation, the prospect of another Tiananmen Square uprising is more than just party officials' paranoia.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.