Isis: US divided over how to defeat Islamic State amid warnings of a 'new Vietnam'

It is only four years since the US pulled its forces out of Iraq, to the relief of the American public weary of a gruelling conflict which had cost 4,425 US lives since the 2003 invasion ousted Iraqi President Saddam Hussein.

Yet America cannot put Iraq behind it.

Last year the US found itself drawn into a fresh conflict in the region, as brutal jihadist group Islamic State carved out a Caliphate across northern Iraq and Syria, massacring thousands, and sparking a humanitarian catastrophe that has seen millions more driven from their homes.

The US claims that a campaign of air strikes against the group has killed 10,000 militants, and that US-trained Iraqi government forces supported by Shia militias are winning the war against Isis in Iraq. In Syria, airstrikes have been launched against Isis positions, and moderate rebels are being trained to take on Isis on the ground.

In Syria, the US has also launched air strikes against the groups's territory in the east of the country and troops are training militias to take on Islamic State on the ground.

Yet critics are unconvinced, and have called for an urgent change of strategy from the Obama administration, pointing to the recent loss of Ramadi by Iraq government forces to an Isis force a fraction of its size as evidence that limiting US engagement to air strikes and training will not defeat the jihadist group.

Frederick Kagan is a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute and one of the architects of the 2007 US 'surge', which saw an extra 30,000 US troops sent to Iraq, a move credited with quelling escalating Shia/Sunni violence during the US occupation.

Kagan believes that the consequences of a failure by the US to commit more troops in the fight against Isis could be catastrophic.

"What will happen if we do nothing is clear: the situation is at best stalemated and most likely will deteriorate in a variety of different ways. If we do nothing we will be establishing an Islamic State in Iraq and Syria in a permanent way, which is a direct threat to US and Britain and the West generally."

President Obama is currently considering sending an extra 1,000 troops to Iraq, to aid the 3,500 already stationed there training Iraqi forces, but Kagan said it was only a fraction of the 15,000-20,000 he recently told Congress was needed if he is to fulfil his promise to "degrade and destroy" Islamic State.

Kagan said that US troops were needed not just to provide behind-the-scenes support but to take on Isis on the battlefield, embedded with Iraqi government forces "both to stiffen their resolve and to bring to bear the full complement of our air power."

The Iraq and Afghan wars have left deep psychological scars in the US, and Kagan acknowledges that there is still resistance to putting American boots on the ground. Ultimately, he argues for a permanent Western military presence in Iraq, "to fight against al Qaeda and embolden it [Iraq] to maintain its independence from Iran."

America is at a crossroads. Gone are the certainties of the Bush administration's neo-conservative "Freedom Agenda", which saw trillions spent attempting to create Western-style liberal democracies in the Middle East. Yet there is also horror at the humanitarian catastrophe unfolding across the region, and concern that the detachment of the Obama administration towards the region is allowing a jihadist movement so brutal it was even renounced by al Qaeda to consolidate its strength.

Recent research shows public opinion tipping in favour of increased US military involvement in Iraq, with 57% telling CBS in February that they supported US boots on the ground, up from 47% in October, and 39% in September. On June 17, the US Congress voted strongly against a proposal to remove US military forces from Iraq. Yet a 2013 poll found 75% of Americans did not think the Iraq war was worth the costs, with the US deeply concerned about the long-term commitment increased military involvement may entail.

"The problem for us is to find the balance between being not in, that is the Republican critique of the current administration, and the position of being all in, which is the current administration's critique of its predecessor. That elusive balance is what this administration is trying to recalculate and tinker with but it is elusive," said Aaron Miller, Vice President for New Initiatives at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, who worked as a Middle East expert at the US Department of State for 24 years, taking a key role in Arab-Israeli negotiations.

For Miller, the US must appreciate there are limits to what it can achieve against Isis, given the Middle East's complex web of alliances and rivalries, and no public support for a military operation of the scale seen in 2003.

"The key to defeating IS is to first reveal that it is incapable of expanding, and then expose it as another bankrupt and ruthless polity that cannot deliver for its constituents," he said. "That in the end would defeat the idea of the Caliphate. But that requires a combination of local power and political will that is just not there," he said.

"We have a risk-averse public, risk-averse Congress and risk-averse administration. The choices are pretty limited, so it comes down to enhanced counterterrorism, with some adjustment in lending support politically and militarily to forces on the ground," said Miller.

For Miller, the perils of sending in a larger US military force to combat Isis on the ground are clear.

"Haven't we seen this before? Haven't we spent a decade and spent $140billion playing precisely this role; spent billions training the Iraqi military only to see much smaller numbers of Isis fighters throw them out of Ramadi and Mosul?" said Miller.

In the absence of an Iraqi army capable of taking on and defeating Islamic State, it is Iran-backed Shia militias which have stepped in and borne the brunt of much of the fighting against IS. Many have been accused of atrocities responsible for worsening the sectarian conflict in the country, and were responsible for deadly attacks against US forces during the occupation. Kagan says that a precondition of closer US involvement would be for Baghdad to sever its reliance on Iran. For Miller, it is unlikely, though, that Tehran would accept a diminished role. "Why would the Iranians want that? They want us out, not in," he said.

"We are 14 years after 9/11 and we are still intensively involved in a fight against al Qaeda and its derivatives, and this should give you some idea of the scale of the difficulty. And IS is different and much more dangerous than al Qaeda. It's got roots."

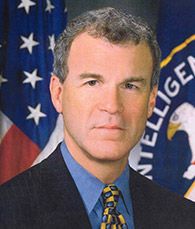

His views are echoed by Robert Grenier, former CIA head of counterterrorism, whose recent book 88 Days to Kandahar describes his days as station chief in Islamabad, building local alliances and planning covert operations in support of the US invasion of Afghanistan.

He said that the lesson of Afghanistan is that success against violent jihadists can only be achieved ultimately by locals.

"The key to success is indigenous forces, and we ought not to achieve militarily what they can't consolidate or sustain," he said.

He warned against the US being drawn into "an Afghan- or Vietnam-like situation where we are overcommitted and not able to do on our own at the end of the day what only Iraqis can sustain".

Though he supports a more "aggressive" stance by the Obama administration, including embedding US troops with Iraqi army units, and providing greater support for local Kurdish and Sunni militias, he said that his time in the front line of the war against terror taught him that there are limitations to what the US can achieve alone.

"I think that the US engagement needs to be relatively small, sustainable and open-ended – to acknowledge the limitations of what we can achieve on the ground. We can provide influence, we can provide support, but ultimately this is somebody else's fight. We have a stake in the outcome so need to be engaged aggressively, with an understanding that there limits to what we can achieve."

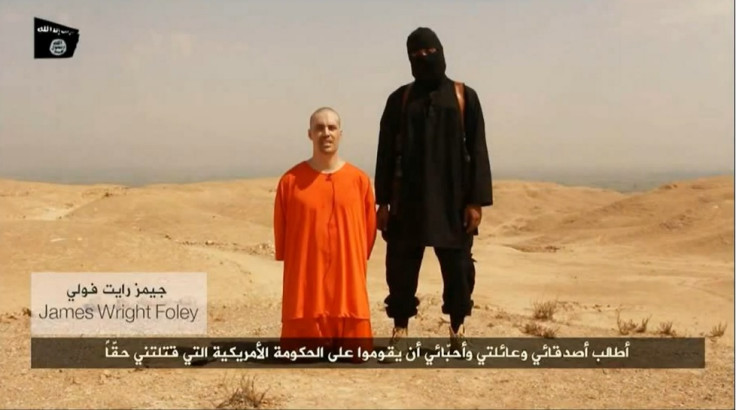

In its propaganda, Islamic State has repeatedly called the US to send troops to engage them on the ground, with the videos of the execution of US hostages believed by experts to be a way of provoking the US into deepening its involvement in the conflict.

Grenier believes that significantly boosting troop numbers could serve as an enormous propaganda boost to Isis, encouraging Isis sympathisers worldwide to join the battle against the "Crusaders".

"If the US takes the lead we are playing into a global narrative that works to IS's advantage, that leading a war against infidel interlopers and elements on ground allied with them.

"[In taking a significantly larger role] We would be taking on responsibility for victory against Isis – then that holds the seed of much larger escalation," he said.

The US public expects dramatic and conclusive victories, but America is no longer the world's single, uncontested economic superpower, and a decade of conflict in the Middle East has exposed the limitations of US attempts to assert its authority in areas of the word deeply suspicious of its motivations.

The war against Isis, Grenier said, is as much about the expectations and assumptions of the US public as it was about American boots on the ground in the deserts of Iraq or Syria.

"In some ways the domestic challenge is the most difficult part of this," he said.

"This strategy is perceived and it is politically unsatisfying to Americans who like to go in quick, dig and win. This situation will not admit that sort of approach. This is a problem to be managed in hopes that working through indigenous actors we will achieve success in the long term. In the short term, this is a problem to be managed rather than solved."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.