Using GPS 'switches off' parts of your brain used to naturally navigate different routes

Navigating London appears to be particularly taxing on the hippocampus, study finds.

Italian explorer Christopher Columbus did not have satnav to guide him on his journey to discover India and his happy accident probably made him a joke in the explorer circles! But for those of us who use satellite technology to find the quickest route to a destination, the results are not always any better.

A recent study, conducted at the University College London, has revealed that parts of our brain "switch off" when we make use of satnav systems. These areas of the hippocampus typically used for memory and navigation as well as the prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for decision-making, stop working when we use GPS.

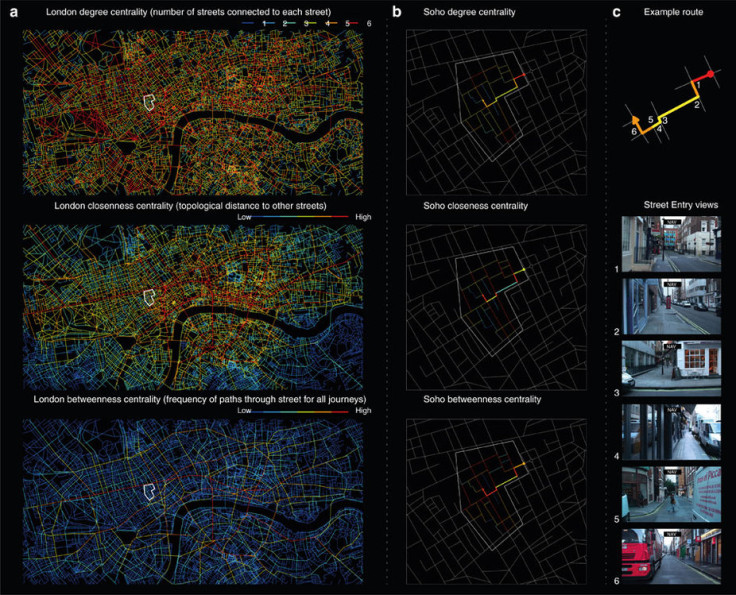

In the study, published in Nature Communications, 24 volunteers were made to undergo brain scans as they navigated a simulation of Soho in central London. When made to navigate new areas manually, their hippocampus and prefrontal cortex showed a spike in activity, but showed no increase when the participants used GPS.

"When we have technology telling us which way to go... these parts of the brain simply don't respond to the street network. In that sense our brain has switched off its interest in the streets around us," Hugo Spiers, neuroscientist and corresponding author of the study explained.

Lead author of the paper, Dr Amir-Homayoun Javadi of the University of Kent believes that the results indicate the shortcomings of satnavs. "Understanding how the environment affects our brain is important. My research group is now exploring how physical and cognitive activity affects brain activity in a positive way. Satnavs clearly have their uses and their limitations," he said.

The experiment also helps scientists compare the ease with which one can navigate various street networks of major cities around the world. London for example, was particularly taxing on the hippocampus due to its complex network of small streets. Moving through Manhattan on the other hand, took much less effort due to the city's grid layout.

Dr Spiers, who works as the director of Science at The Centric Lab, a London-based consultancy and research organisation, believes the information collected from the study can help create better-designed cities.

"The next step for our lab will be working with smart tech companies, developers, and architects to help design spaces that are easier to navigate and increase wellbeing," he said. "Our new findings allow us to look at the layout of a city or building and consider how the memory systems of the brain may likely react. For example, we could look at the layouts of care homes and hospitals to identify areas that might be particularly challenging for people with dementia and help to make them easier to navigate. Similarly, we could design new buildings that are dementia-friendly from the outset."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.