Vast and strange donut-shaped mounds discovered behind Great Barrier Reef

The reef is made up of huge fields of strange donut-shaped circular mounds measuring 200-300m across

A vast reef has been discovered hiding in plain sight behind the Great Barrier Reef – the world's largest living structure. The finding was made by a collaborative team of researchers from James Cook University (JCU), the University of Sydney and Queensland University of Technology (QUT), using laser data from the Royal Australian Navy.

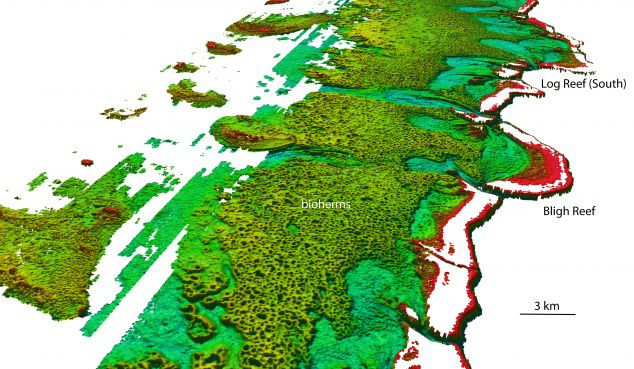

High-resolution seafloor data proved by aircraft equipped with LiDAR – a detection system which works like radar, but using light from lasers rather than radio waves – has uncovered great fields of unusual donut-shaped circular mounds, each measuring 200-300 metres across and up to 10 metres deep at the centre, next to the Great Barrier Reef. The research has been published in the Springer journal.

"We've known about these geological structures in the northern Great Barrier Reef since the 1970s and 80s, but never before has the true nature of their shape, size and vast scale been revealed," said Dr Robin Beaman from JCU. The deeper seafloor behind the familiar coral reefs amazed us."

The fields of donut-shaped rings are in fact, Halimeda bioherms – large reef-like geological structures which are formed by the growth of Halimeda, a common type of green algae made up of calcified segments. When Halimeda die, they form small limestone flakes which, over time, build up into large reef-like mounds, or bioherms.

The extent of these bioherm fields is vast says Mardi McNeil, lead author of the study from QUT. "We've now mapped over 6,000 square kilometres. That's three times the previously estimated size, spanning from the Torres Strait to just north of Port Douglas. They clearly form a significant inter-reef habitat which covers an area greater than the adjacent coral reefs."

Associate Professor Jody Webster from the University of Sydney said the new information about the extent of the bioherm fields will raise pressing questions about its vulnerability to climate change. "As a calcifying organism, Halimeda may be susceptible to ocean acidification and warming. Have the Halimeda bioherms been impacted, and if so to what extent?"

Dr Beaman said the discovery has opened up multiple new avenues of research. "For instance, what do the 10-20 metre thick sediments of the bioherms tell us about past climate and environmental change on the Great Barrier Reef over this 10,000 year time-scale? And, what is the finer-scale pattern of modern marine life found within and around the bioherms now that we understand their true shape?"

He said future research would require further exploration of the sediment and the geophysical features below the surface, while autonomous underwater vehicles could be deployed to learn more about the chemical, biological and physical process of the structures.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.